In early 2020, when I was considering where I would focus on as part of my yearly project for this blog, I came to the conclusion that I would continue my work with the Japanese Colonial Era.

Albeit with a bit of a caveat.

I decided that I’d make an effort to visit some of the various “Martyrs Shrines” around Taiwan.

But only those which were originally home to a Shinto Shrine.

Taiwan was once home to well-over two hundred Shinto Shrines, but as one colonial regime was replaced by another, the majority of them ended up getting smashed to pieces.

In my post about the National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine (台北忠烈祠) in Taipei, I listed fifteen of these former Shinto Shrines around Taiwan (and on Penghu) that continue to exist in some form today.

Some of which I’ve already posted about:

National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine (國民革命忠烈祠)

New Taipei City Martyrs Shrine (新北市忠烈祠)

Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine (桃園忠烈祠)

Tungxiao Martyrs Shrine (通宵忠烈祠)

Taichung Martyrs Shrine (台中忠烈祠)

Changhua Martyrs Shrine (彰化忠烈祠)

Yilan Martyrs Shrine (宜蘭忠烈祠)

That’s seven, so if your math is good, you’ll probably realize that I still have eight to go!

That means that this project is just going to be (yet another) one of my ongoing projects when the new year hits and 2020 is finally over.

Before that happens though, I will be crossing another two off of my list!

If you’re reading this and aren’t entirely aware what a ‘Martyrs Shrine’ actually is, I recommend taking a few minutes to read my article about the National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine (linked above), where I go into greater detail about what they actually represent.

But for those of you who can’t be bothered, they’re basically war memorials for fallen members of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces, and tend to be propaganda-like symbols of the several decades of authoritarian history that was imposed on the people of Taiwan.

Having little to do with Taiwan, or the people of this country, the Martyrs Shrines you’ll find around the nation today (for the most part) memorialize the fallen members of the ROC military who died during the various conflicts that took place between 1912 and 1958.

Now that we’ve got that over with, Today, I’ll be introducing both the former Taitung Shinto Shrine and the Taitung Martyrs Shrine that stands in its place today.

I’ll start with the history of the Taitung Shinto Shrine and provide some historic photos of the once beautiful shrine and then go into detail about the current Martyrs Shrine that replaced it.

Taitung Shinto Shrine (臺東神社)

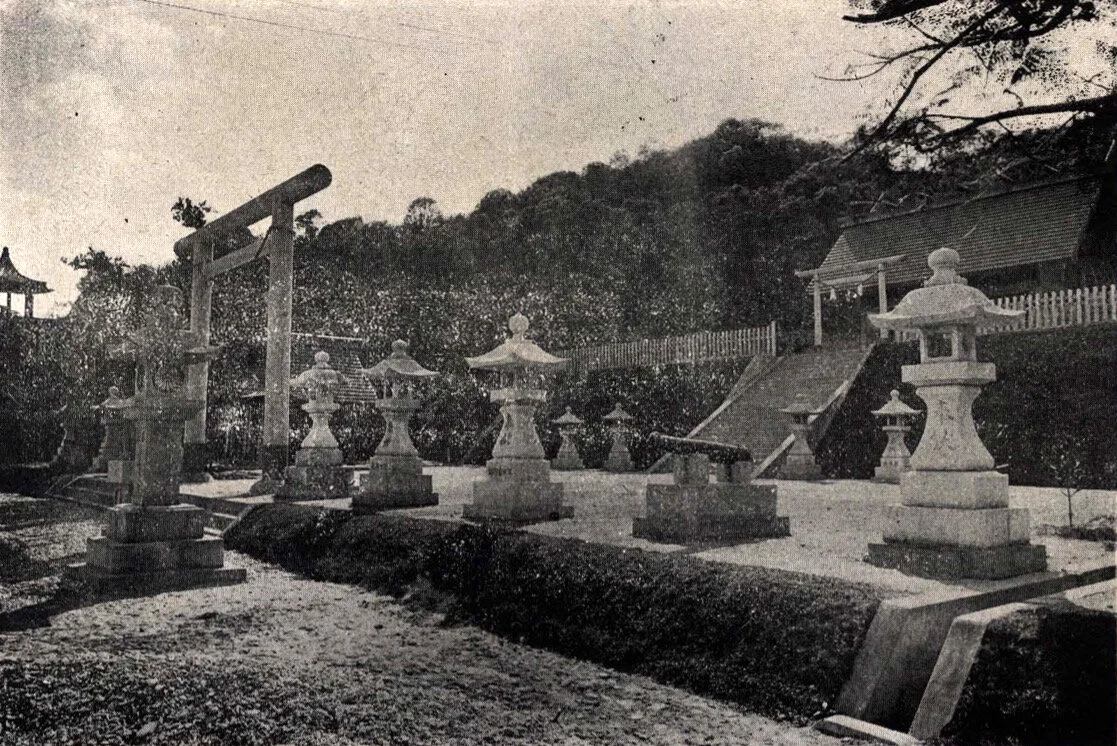

The Taitung Shinto Shrine (たいとうじんじゃ), otherwise known as the “Taito Jinja” was during its heyday regarded as one of the most beautiful Shinto Shrines in Taiwan.

Construction (on the first iteration of the shrine) started in 1910 (明治43年) and opened to the public a little over a year later on October 27th, 1911 (明治44年).

The original shrine however was located in an area in the western district of the city, which was simultaneously being developed for the various industries important to the economy, most importantly the sugar and timber industries.

In 1924 (大正13), the shrine received an upgrade in its official status to a Prefectural Shrine (縣社), which meant that it was the most important of all the shrines in Taitung.

Link: Modern system of ranked Shinto Shrines (Wiki)

Soon after the shrine received its upgraded designation, a number of accumulating factors forced the local government to re-locate it to another part of town.

The first problem was that (as I mentioned above) Taitung was becoming highly developed thanks to the success of the commodity economy. The neighborhood where the shrine was located likewise became important as a residential space for many of the Japanese engineers and specialists who came to Taiwan, which is considered inauspicious for a shrine of its status.

The next issue was a structural one, and a lesson learned for Japanese builders in Taiwan who quickly had to adapt to the very real problem of termites which were having a feast on their buildings.

Only a decade after opening, the termite problem had become so serious that structural issues became pretty much irreparable.

The final factor contributing to the shrine’s relocation coincided with the celebrations of the succession of Prince Hirohito (裕仁皇太子) to the imperial throne as Emperor Showa (昭和天皇), ushering in a new era for the Japanese Empire.

Once a suitable location was found, plans were made to build an even larger and more beautiful shrine.

Construction on the second generation of the shrine started in October of 1928, coinciding with the enthronement ceremony (即位禮 / 即位の礼) for the new emperor and was completed in the summer of 1930 (昭和5年).

Located on Liyu Mountain (鯉魚山), near the (former) Taitung Train Station (台東舊站), the completed shrine occupied around 70 acres of land (86,000坪.)

The newly consecrated shrine, which quickly became known as one of the most beautiful in Taiwan, consisted not only of an excessively large patch of land on the side of a small mountain, but everything you’d expect to find at a shrine of its importance:

Two large gates or “Torii” (鳥居)

A beautiful walking path or “Sando” (參道)

Stone Lanterns or “Toro” (石燈籠) on either side of the walking path.

An Administration Office or “Shamusho” (社務所)

A Purification Fountain or “Chozuya” (手水舍)

Stone Guardians or “Komainu” (狛犬)

A Hall of Worship or “Haiden” (拜殿)

A Main Hall or “Honden” (本殿)

As was the case with most of Taiwan’s larger Shinto Shrines during the colonial era, the kami enshrined within were all familiar figures which included the Three Deities of Cultivation and Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa.

The ‘Three Deities of Cultivation’ (かいたくさんじん / 開拓三神), consist of three mythic figures known for their skills with regard to nation-building, farming, business and medicine.

The three gods are as follows:

Ōkunitama (大國魂大神 / おおくにたまのかみ)

Ōkuninushi (大名牟遲大神 / おおなむちのかみ)

Sukunabikona (少彥名大神 / すくなひこなのかみ)

The first mention of these deities was in the ‘Birth of the Gods’ (神生み) section of one of Japan’s most important books, the ‘Kojiki’ (古事記), or “Records of Ancient Matters”, a thirteen-century old chronicle of myths, legends and early accounts of Japanese history, which were later appropriated into Shintoism.

While these three deities date back well-over a thousand years, the other one that was enshrined within the Taitung Shinto Shrine was a considerably younger one.

In fact, most of the over two hundred Shinto Shrines constructed in Taiwan during the colonial era, most were home to shrines dedicated to Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王.)

Prince Yoshihisa had the unfortunate luck of being the first member of the Japanese royal family to pass away while outside of Japan in more than nine hundred years.

The reason why his worship is so prevalent here in Taiwan is due to the fact that it is believed to have died of malaria in Tainan in 1895 - although it is also thought that he might have been shot by Taiwanese guerrillas.

Link: Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (Wiki)

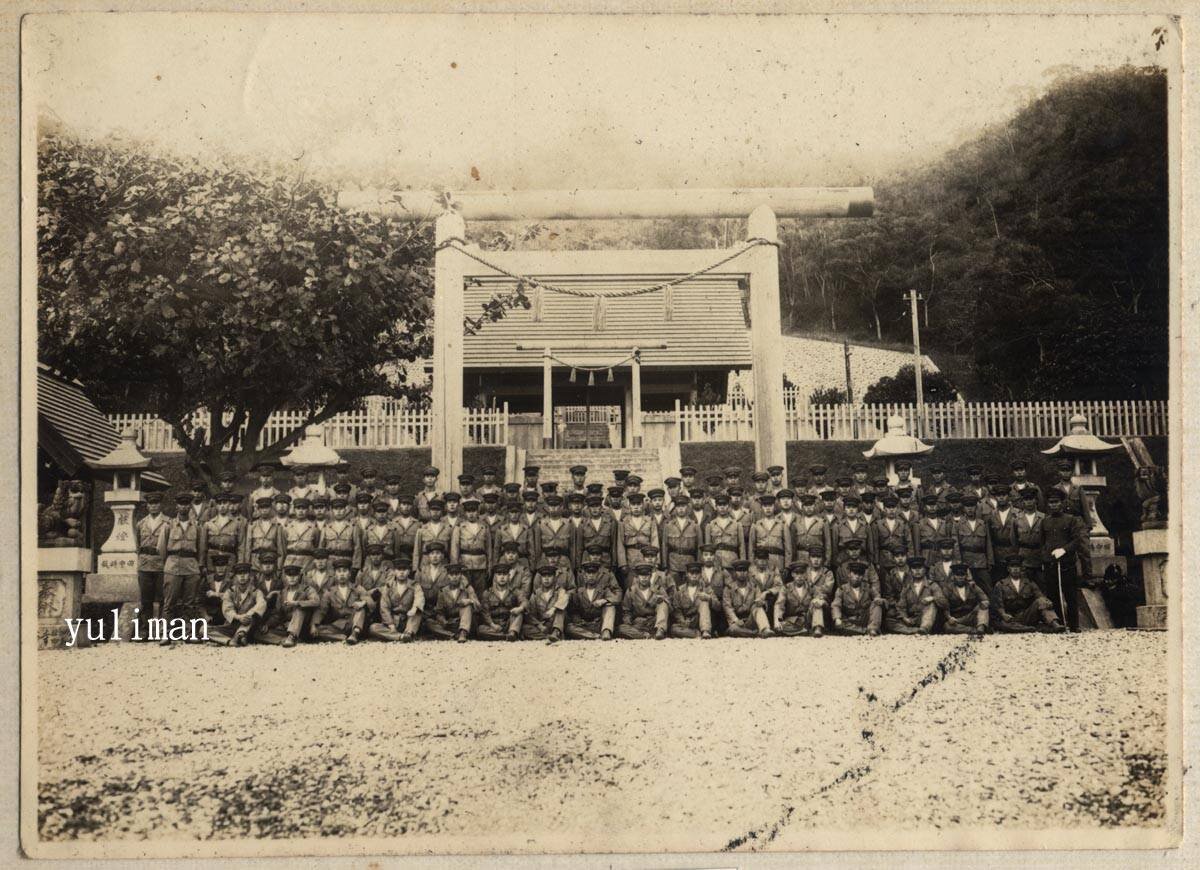

As the most important place of worship in “Taito Prefecture” (台東廳 / たいとうちょう), the shrine was frequently visited by civil servants, members of the military and schools that brought students on field trips.

This was especially the case during the latter years of the colonial era when the colonial government attempted to forcibly assimilate the local population into full-fledged Japanese citizens.

Link: Japanization (Wiki)

While I’m not going to delve too deeply into the arguments for or against such policies, if there was anything good that came out of these policies, its that when people visited the shrine, they often took group photos, like the one above.

Link: Yuliman (TIPGA)

Why would I argue that these photos are so important?

Well, those photos all we currently have on record to show the beauty of the shrine. They also tell an important story about Taiwan’s modern history, which is something that should be discussed and debated.

When the Second World War ended and control of Taiwan was (ambiguously) relinquished to the Republic of China (中華民國), the shrine was converted into a Martyrs Shrine and was eventually torn down and replaced by a Chinese-style shrine.

Even though the Shinto Shrine was torn down, it wasn’t completely destroyed.

You can still find fragments of the original shrine lying around and/or vandalized.

Likewise you can still enjoy the original layout of the Walking Path as well as the various layers of the shrine that once existed.

So, even though a Chinese-style shrine exists in its place today, a considerable amount of evidence remains of the beautiful shrine that it was once home to.

Taitung Martyrs Shrine (台東縣忠烈祠)

Bear with me for a few minutes. I need to complain.

Researching this shrine has been a pain in the ass.

Factual, verifiable historic information about the Taitung Martyrs Shrine is excruciatingly difficult to find.

Websites in Taiwan are notoriously unreliable and most of the information that was once available, results only in server errors.

Unfortunately this is a problem that seems all too common with official resources in Taitung, especially those coming from the government.

So, I went to some libraries and found next to nothing worthwhile.

Additionally, from what little historical information I did find, it seems like the shrine has been renovated and reconstructed on several occasions.

Few of those important dates or historical facts are very well recorded.

All of this might seem a little strange, but after visiting the shrine, I have to say it’s also not particularly all that surprising.

How long the original Shinto Shrine lasted after the Chinese Nationalists arrival in Taiwan is unclear, but as early as the 1950s, things at the shrine started to change with the Japanese-style buildings gradually being torn down and replaced with Chinese-style structures.

In a government produced promotional video from 1966 (民國55年) about the development of Taitung, titled: “進步中的台東縣專輯” (Youtube), we can see people visiting the shrine, with several of the Shinto Shrine’s lanterns and much of the layout still intact.

That being said, by that time the gates, Hall of Worship and Main Hall all appear to have been replaced.

As early as 1953 (民國42年), the local government replaced the on-site monument dedicated to Japanese police (警察忠魂碑) with a monument dedicated to a local figure from the Qing Dynasty, Hu Tie-Hua (胡鐵花).

In 1961 (民國50年) the name of the shrine was officially changed to the “Taitung County Martyrs Shrine” (台東縣忠烈祠).

The Martyrs Shrine continues to follow the same layout as the original shrine, but it should go without saying that there have also also been some significant changes.

In an attempt to hide the fact that there was once a beautiful Shinto Shrine here, an effort was made to remove anything “Japanese-related” from the site. To that effect, the original gates, lanterns and buildings were all torn down and replaced.

The irony of this is that it’s rather obvious that someone went on a smashing spree, but when they were done they ended up leaving quite a few pieces of the original shrine lying on the ground and never really bothered to clean up their mess.

So, even though this section is meant to introduce the Martyrs Shrine, I’m going to introduce it through the lens of the original shine.

The Visiting Path (參道)

The original Visiting Path for the Shinto Shrine today retains quite a few of its original features and is still quite beautiful. The path is currently a tree-covered road that maintains its original width and the layered pedestals where the stone lanterns were originally placed, have since been replaced with floral arrangements.

the Stone Lanterns (石燈籠)

There’s not much on display here, except for some pettiness.

The original stone lanterns have pretty much all been smashed to pieces. What little remains have been awkwardly painted over with the original dates and references to the “Showa” era filled in.

In terms of the remnants of the shrine that have been left lying around, the stone lanterns make up the majority and the way they have been disrespected is quite disheartening, but not entirely surprising, all things considered.

The Shrine Gate (鳥居)

While the original Torii has been removed, it has been replaced with a beautiful Chinese-style Pailou (牌樓) gate and has kept two of the original stone lions which stand guard to the let and right of the gate

The gate is painted red with a golden temple-style roof on the top and has the Chinese characters “忠烈祠” in the centre, which means “Martyrs Shrine,” while the characters on the back read: “浩氣千秋” or “A noble spirit that lasts for eternity.”

Once you’ve passed through the gate, you will be in the area where the Purification Fountain and the Administration Building would have been located.

Today, the area is used instead as a parking lot by the local people who show up to hang out with friends in the park near the shrine.

It is also somewhat of a graveyard for the Shinto Shrine as you’ll find quite a few objects randomly laying around on the ground.

As you continue along the path you’ll reach a wall with a set of stairs, which is where the inner-most parts of the original Shinto Shrine were located.

Hall of Worship (拜殿)

Once you’ve walked up the stairs to the next section, you’ll be met with a beautiful pavilion, known as the “Memorial Hall” (祠堂) where the Shinto Shrine’s Hall of Worship used to stand.

While it is a shame that the original building has been torn down, the current pavilion is quite beautiful and isn’t typical of what you’d usually find at Martyrs Shrines or at other temples in Taiwan.

The pavilion is painted with the same colour scheme as the shrine gate below, but has a blue large placard (匾額) on the front with Chinese characters that read “正氣昭垂”, which translates literally as “Righteous Vigor” and is dedicated to the many martyrs of “後山” (back mountain), who died protecting their homeland from the Japanese.

A few notes here with this one:

The ‘martyrs’ being memorialized here are both Chinese and Indigenous peoples alike, who were killed prior to or during the Japanese occupation.

These martyrs however ironically don’t include the indigenous people who were murdered by the Chinese who came to settle in the area prior to the Japanese Colonial Era.

A convenient omission.

Likewise, “Back Mountain” (後山) is the name Taitung was once referred to by the Qing and in English sounds a bit like “backwater” which isn’t all that flattering. If I was from Taitung and someone from Taipei referred to my home that way, I might want to knock their pretentious ass on the ground.

The Main Hall (本殿)

The Main Hall of the Martyrs Shrine and the Main Hall of the Shinto Shrine are actually located in the exact same spot.

In the past, the Main Hall of the Shinto Shrine, like all Shinto Shrines, would have been off-limits to the general public.

It was placed a level above the Hall of Worship and the only people that were able to ascend to that level would have been the priests who took care of the shrine.

Today, we’re free to walk up and approach the Main Hall, but some things remain the same in that the shrine is pretty much closed to the public all year-long.

Why is the shrine room of the Main Hall shut with a pad-lock for most of the year? Well, there are probably a few reasons for this.

My guess however is that it is because no one really wants to visit the shrine every day to open it up, clean the interior and close it up again at the end of the night.

My reason for thinking this might seem harsh, but from the condition of the rest of the shrine tends to point in that direction.

This shrine certainly needs a little bit more TLC than it is currently afforded, and if the Taitung City Government wants to make it a proper tourist attraction, they should probably take better care of it.

Unfortunately at this point, the shrine seems like somewhat of an afterthought for the local government.

The Main Hall is currently a Chinese-style structure and features the same colour scheme as what you’ve already seen below.

What stands out most is that as you walk up the stairs, you’ll be met with a roof-covered walkway that brings you to the front door of the shrine.

The front door of the shrine has two Door Gods (門神) on the front with a pad-lock between them.

The rest of the building is quite small, but is nicely constructed with traditional architecture and a beautiful sloping roof.

One thing you’ll want to pay close attention to when you’re on the same level as the Main Hall are the trees on the left and right of the building. These trees were planted at the same time as the construction of the Shinto Shrine and today are more than a century-old and tower over the building.

They also provide some beautiful shade for the building and some great light for photographers.

Even though I wasn’t able to take photos of the interior of the shrine, I was able to peer in through the windows at the small shrine.

The worship area of this Martyrs Shrine is considerably smaller than its counterparts around Taiwan and doesn’t feature as many Spirit Plates (牌位) as the others, but it probably still serves the same function.

The fact that the shrine isn’t open to the public shouldn’t really deter anyone from visiting. You’re honestly not really missing out on very much with the room not being open.

The beauty of the shrine, which is surrounded by nature is something that is really nice and the separation between the “city” and the “mountain” here is quite relaxing.

Getting There

Getting to the Taitung Martyrs Shrine is quite easy as it is located within the downtown core of Taitung City and is close to a number of other important attractions.

Address: #500, Bo’ai Road, Taitung City (台東縣台東市博愛路500號)

If you’re staying in Taitung, getting to the shrine is quite simple and easily walkable. On the other hand, if you’re staying elsewhere (or not staying at all), never fear, the area near the shrine is easily accessible and has lots of parking for cars and scooters.

In terms of public transportation, the only bus that stops near the shrine is the Downtown Sightseeing Bus, which stops outside the Taitung Stadium across the street from the shrine.

There are also a number of other buses coming from all over Taitung and elsewhere that stop directly at the nearby Taitung Bus Station (台東轉運站), which is a short walk from the shrine.

Unfortunately the most complete resource on the web about the buses that pass through the Taitung Bus Station can only be found on Wikipedia and only in Chinese.

For some strange reason almost all of the resources about the buses, including the bus station’s website itself have been taken down.

Link: 台東轉運站 (Wiki)

Located within the Liyu Mountain Park (鯉魚山公園), the shrine is directly across the street from the Taitung County Stadium (台東縣立體育場) as well as the popular Taitung Railway Art Village (鐵道藝術村).

Although locals tend to park (illegally) near the entrance of the shrine, if you’re driving a car or scooter, you should probably park along the road near the stadium where there are a generous amount of spaces.

From there the shrine is just a short two minute walk up the hill at the base of Liyu Mountain.

Once you’ve finished checking out the Martyrs Shrine, you’ll probably want to head to the right of the shrine to check out the Longfeng Buddhist Temple (龍鳳佛堂) as well as the pagoda that shares its name next door.

Likewise, you may want to continue the short hike up the trails to the various viewing platforms on Liyu Mountain, where you’ll be able to enjoy excellent views of the Taitung City skyline and the Pacific Ocean in the distance.

Although the Taitung Martyrs Shrine is located on the side of a picturesque mountain overlooking the city, retaining a similar layout to the once beautiful Shinto Shrine that stood in its place, today it is unfortunately unkept and uncared for.

I’ve visited quite a few of these Shinto Shrines that have been converted into Martyrs Shrines around Taiwan and I’m sad to say that this one was probably the most disappointing of the bunch.

Not only does it seem like no one really cares about its existence, the city government does little to take care of it or the landscape that surrounds it.

This is only exasperated by the fact that there are signs pointing tourists in the direction of the shrine, only to find the actual shrine bolted shut with no opportunity to look inside or even learn about its purpose.

Should you visit the Taitung Martyrs Shrine? Of course.

You should definitely include a stop by the shrine during any tour of the historic area of downtown Taitung near the former train station. But it is a stop that won’t take too much time and will allow you to visit a bunch of other locations within the city.