Translated literally into English as “Eastern Eye Mountain,” the Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Park in Taoyuan has gone through what many would consider a surge in popularity over the past few years.

With the COVID-19 pandemic putting international tourism to a sudden halt, people in Taiwan were (probably for the first time in their lives) forced to look at destinations within their own borders for places where they could enjoy a bit of travel, while also staying safe from the virus.

Amazingly, despite the pandemic dealing a pretty harsh blow to international tourism, with little other option, the people of Taiwan it seems have started to appreciate their beautiful country a little more than they did in the past. For years, I’ve been standing here with a megaphone trying to convince people that Taiwan is one of the most beautiful countries in the world, but apparently all it took was a global pandemic to push people to come to the same conclusion.

In truth, it doesn’t really matter what caused this seismic shift in attitude with regard to domestic tourism in Taiwan. The important thing is that people have become content traveling around the country and enjoying its natural beauty. This has become especially true for the youth of the country, who have taken to outdoor activities like hiking mountains, river tracing, rock climbing, snorkeling, scuba diving, etc. Weekends and holidays typically see people traveling from one end of the country to the other to enjoy the hundreds of hiking trails or to the few areas of the island where the coral reef remains alive and well.

This sudden surge in domestic tourism, especially with regard to outdoor recreation, has forced something of a ‘reset’ with regard to how tourism is marketed around here. The pandemic may have forced the unfortunate closure of a number of the nation’s international travel agencies, but it has spawned a growing number of companies that have adapted by planning events to the mountains, outlying islands and even offering scuba-diving packages to those wanting to learn. Similarly, even though the nation’s beautiful mountains have always been accessible, the surge in interest in hiking them has forced the government to improve infrastructure in these areas, allowing more and more people to enjoy all of the breathtaking beauty that Taiwan has to offer.

One of the areas that have benefited most from this surge in domestic tourism are the nation’s ‘Forest Recreation Parks,’ which tend to be large mountainous parks where people of all ages can enjoy leisurely walks through the forest or difficult hikes to alpine mountain peaks. Some of these parks, Alishan (阿里山) and Taipingshan (太平山), for example, have always enjoyed the love and adoration of the Taiwanese public, but with more a dozen of similar parks across the country, people have started to take an interest in the others as well.

As the only one of these parks located in Taoyuan, and one of the most easily accessible within Northern Taiwan, the Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Park is one of those destinations that has received a considerable amount of attention over the past few years.

That being said, as an avid hiker, and one of the few vocal lovers of Taoyuan, I have to admit that over all of my years of living in Taiwan, I’m guilty of being a bit like everyone else in that I’ve only recently discovered the beauty of this National Forest Park. Nevertheless, now that Taiwan has reopened for international tourism, its important that destinations like this receive the attention they deserve, especially from foreign writers like myself.

I hope that this guide to the park, and the photos I’m sharing today help to convince you that a day-trip to Dongyanshan, whether it be with a tour group, or on your own, is well worth the time and effort that it takes to get there. Before I start talking about the park though, it’s probably a good idea to briefly introduce these ‘National Forest Parks’ so that you have a better idea of what to expect.

Taiwan’s National Forest Recreation Parks

Established by the Forestry Bureau in 1965 (民國54年), the government has designated a number of Taiwan’s mountainous areas as protected ‘Forest Recreation Parks’ (國家森林遊樂區). Over the six decades since these protected areas were established, the number of parks on the list has grown significantly, with many of them once utilized by the Forestry Bureau for the purpose of extracting natural resources.

Currently there are twenty-two designated areas around the country that have established Forest Recreation Parks, but that list of parks can often be somewhat confusing, even for locals, given that they often receive slightly different designations, and may or may not be included within what are considered National Parks (國家公園) or National Scenic Areas (國家級風景特定區). Officially, the list includes some twenty-two established areas, which are classified simply as ‘Forest Parks’ or ‘Forest Wetland Parks’, making the actual number of these spaces slightly misleading, given that they differ greatly in size and scope.

Nevertheless, no matter how you classify them, these parks range from tropical monsoon forests in the south and east of the country to temperate high-mountain forests in northern and central Taiwan. In each case, the Forestry Bureau has developed a system of walking paths and hiking trails within where visitors are able to enjoy the natural beauty of Taiwan at their leisure.

Below, I’ve compiled a list of the (current) areas classified as 'Forest Recreation Areas,’ each of which have become popular with local and international tourists, with a few of them becoming rather iconic.

-

Taipingshan Forest Recreation Area (太平山國家森林遊樂區)

Manyueyuan Forest Recreation Area (滿月圓國家森林遊樂區)

Neidong Forest Recreation Area (內洞國家森林遊樂區)

Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Area (東眼山國家森林遊樂區)

Guanwu Forest Recreation Area (觀霧國家森林遊樂區)

Mingchih Forest Recreation Area (明池國家森林遊樂區)

Wuling Forest Recreation Area (武陵國家森林遊樂區)

Basianshan Forest Recreation Area (八仙山國家森林遊樂區)

Dasyueshan Forest Recreation Area (大雪山國家森林遊樂區)

Hehuanshan Forest Recreation Area (合歡山國家森林遊樂區)

Aowanda Forest Recreation Area (奧萬大國家森林遊樂區)

Alishan Forest Recreation Area (阿里山國家森林遊樂區)

Tengjhih Forest Recreation Area (藤枝國家森林遊樂區)

Kenting Forest Recreation Area (墾丁國家森林遊樂區)

Shuangliu Forest Recreation Area (雙流國家森林遊樂區)

Jhihben Forest Recreation Area (知本國家森林遊樂區)

Siangyang Forest Recreation Area (向陽國家森林遊樂區)

Chihnan Forest Recreation Area (池南國家森林遊樂區)

Fuyuan Forest Recreation Area (富源國家森林遊樂區)

Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Park

The ‘Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Park’ was established in 1991 (民國80年) on 916 hectares of land within Taoyuan’s mountainous Fuxing District (復興區). Originally home to the Llyung Topa (拉流斗霸) of the Tayal Indigenous people (泰雅族), the park, which spans an elevation from altitude of 650 - 1,212 meters above sea level sits on the western edge of Taiwan’s Snow Mountain Range (雪山山脈), and acts as a natural barrier separating the east of the country from the west, protecting Taoyuan and New Taipei City from typhoons and the northeast monsoon.

More commonly known these days as the Dabao Tribe (大豹社), named after the Dabao River (大豹溪) that flows from the mountains into Sanxia, a lot closer to the Manyueyuan Forest Recreation Park. In the late 1800s, the indigenous people were essentially pushed out of their homes, fleeing into the mountains, first by the Qing and then the Japanese.

The sad story started when the Qing government removed its prohibition regarding entering Taiwan’s mountainous regions (開山撫番). Shortly after, the Chinese started making their way into the territory of the Dabao Tribe in order to extract the area’s rich camphor reserves, resulting in the Takoham Incident (大嵙崁社事件), a violent affair that left many on both sides dead.

Later, when the Japanese took control of Taiwan, a similar push into the mountains took place, resulting in guerilla warfare between the indigenous people and the Japanese loggers. Eventually, the Governor-General sent the army marching into the mountains and pushed the Indigenous people out of their ancestral homes.

The encroachment of the Japanese on indigenous territories across the island often resulted in violence and misery for Taiwan’s indigenous people, but as they stood in the way of the empire’s ambition for the extraction of the island’s precious natural resources, the violence was relentless and unforgiving.

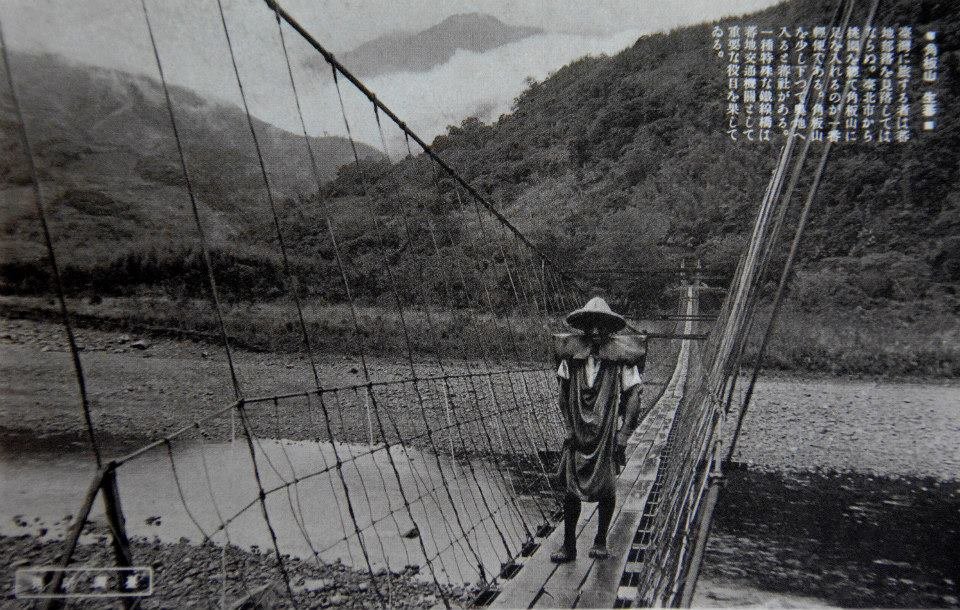

By 1907 (明治40年), the Japanese had pushed their way from Abohei (Amuping / 阿姆坪) all the way to Kappanzan (Jiaobanshan / 角板山 / カッバンソァン), and once the area was firmly under their control, they started to develop a number of facilities dedicated to ensuring the efficiency of the extraction of natural resources from the mountains. Obviously, camphor (樟腦) was at the top on their list of resources to extract, and the area we refer to as Dongyanshan today became an important one for the Timber Industry (林業).

Realizing the extraction of camphor from the area wasn’t a sustainable industry, the Japanese brought with them scientists who set up a research station in Kappazan to search for breakthroughs in the cultivation of cinchona (金雞納樹), a flowering plant known for its medicinal value, especially with regard to treating malaria. In the areas where the cultivation of the plant wasn’t feasible, they ended up reforesting these areas with Japanese cedar, which was also incredibly important for the future development and construction projects across Taiwan.

When the Japanese-era came to an end in 1945, the extraction of camphor continued throughout the post-war era, pretty much until the supply was depleted. Afterwards, the focus of the timber industry shifted to the extraction of cedar which, (ironically was predominately sold back to the Japanese) continued for several decades until it was decided to convert the area into a Forest Park under the 1965 (民國54年) law mentioned above.

As Northern Taiwan’s largest Forest Recreation Park, the Forestry Bureau has done an excellent job creating a network of hiking trails combined with educational resources about the area’s history, making a visit both educational and enjoyable at the same time. Famed for it’s tall cedar forests and it’s ‘sea of clouds’ (雲海), Dongyanshan is not only home to stunning hiking trails, but a large collection of fossils, dating back almost thirty million years to a time when Taiwan was still submerged in the Pacific Ocean.

The park is also home to a number of indigenous animal, insect, and bird species, which you might be lucky enough to encounter during a hike through the forest. Obviously, the most outgoing of the bunch are the Formosan Rock Macaques (台灣獼猴), but you may also be lucky to encounter Red-bellied Squirrels (赤腹松鼠), Formosan Hares (台灣野兔), frogs, snakes, and other smaller reptiles, such as the Formosan pangolin (台灣鯪鯉). The area is also a paradise for bird watchers, so if you’re into that kind of thing, you might want to bring some binoculars along with you!

Points of Interest (東眼山景點)

With the park’s surge in popularity over the past few years, it has also undergone some changes with the addition of some points of interest that help to ensure that a trip there is accessible for one and all. So, before I move on to introducing the trails within the park, I’ll offer a brief introduction of some of the facilities within, so that you have a better idea of what to expect when you visit.

It’s important to keep in mind that although I’m providing a map of the park, it’s essentially the most recent one that is available. Things may ultimately change with the park facilities in the future, so if you visit, I highly recommend grabbing a park brochure at the ticket booth, which will provide the most recent map.

Restrooms (廁所)

Never fear, Dongyanshan Forest Park is a very family-friendly space and unlike most hiking trail across the country, you’ll find that there are several washroom facilities available to hikers and tourists. There are restrooms located within the Tourist Visitor Center as well as several recently constructed facilities along the trails as well - If you find yourself in need, just check out the map of the park given to you at the ticket booth, which displays the locations of all the restrooms.

As I’m writing this article, there are nine different washroom facilities within the park, so you shouldn’t have much trouble finding a space to relieve yourself should you need to.

Pavilions / Picnic Spots / Rest Areas / Viewing Platforms

Within the park, you’ll find a number of spots where you can stop to rest and enjoy some snacks or drinks with your family, friends and fellow hikers. These spaces offer covered protection from the elements in case of rain, so if you need a space to rest, you’ll find these spots conveniently marked on the map. Similarly, along the Self-Guided Trail, you’ll find three different viewing platforms where you can enjoy some scenic views of Taoyuan and New Taipei City. These platforms aren’t covered, but they do allow hikers to sit and enjoy snacks at their leisure.

Tourist Visitor Center (遊客中心)

Located at the base of the hiking trailheads, the Tourist Visitor Center is an excellent place for groups to meet up prior to or after finishing a hike. The building features a small cafeteria where you can purchase some food, snacks or drinks. It is also home to a pretty nice restroom area where visitors can relieve themselves before or after a hike.

There’s also a free filtered water machine where you can fill up a water bottle with hot, warm or cold water for free.

The Visitor Center also comes equipped with some educational exhibition spaces with informative displays about some of the fossils found within the park as well as a description of the vegetation and animals that make their home within the park.

Dongyanshan Restaurant (東眼山食堂)

The recently opened Dongyanshan Restaurant is located within a beautifully designed building a short distance from the Visitor Center. Taking into consideration the location of the park, it shouldn’t really surprise anyone that the menu is quite limited. Offering set menus (with vegetarian options), fried snacks and various beverages, it’s certainly not a Michelin-quality restaurant, but if you’re hungry and in need of something to eat, it’s a pretty good option.

However, it’s important to keep in mind that the ‘Set Menu’ dishes are only available from 11:00am - 1:30pm while the ‘Afternoon Tea’ fried dishes are available from 2:00 until the restaurant closes.

Reforestation Memorial Stone (造林紀念石)

Located at the end of the Forestry Trail, you’ll find a memorial stone that commemorates the reforestation effort that helped to bring the forest back to life, giving us the beautiful park that we’re able to enjoy today. The memorial isn’t really that much to look at, and it essentially just marks the end of the trail, but it’s an important reminder that this are was once completely clear cut.

Dongyanshan Hiking Trails (東眼山健行步道)

Within Dongyanshan Forestry Park there are essentially three major trails, with a number of off-shoots that connect with other trails, and extend beyond to much longer and more challenging hikes. With a combined length of around sixteen kilometers, you’ll have to choose carefully which trail to hike on your visit, because you probably couldn’t finish them all in a single trip. Most visitors are likely to choose between the ‘Self-Guided Trail’, the ‘Scenic Trail’ or the ‘Forestry Trail’, but for those who are a bit more serious, they might simply be making use of the leisurely trails to extend their hike to ‘Dongman Trail’ (東滿步道) or onto ‘Mount Beichatian’ (北插天山), which aren’t for the faint of heart.

The Self-Guided Trail (自導式步道)

Starting at the Dongyanshan Visitor Center (東眼山遊客中心), the nearly four kilometer-long ‘Self-Guided Trail’ is a bit awkwardly named in that it might mislead some visitors into thinking that the other trails require a tour guide, which isn’t actually the case. This trail is essentially a loop through some of the most stunning natural scenery that Dongyanshan has to offer, and culminates at the highest point of the park, which is essentially the peak (三角點) at 1,212 meters.

Along the way you’ll get to enjoy ridge-lines with stunning views of Taoyuan and Sanxia, and if the weather is good, you may even catch a view of Taipei 101 in the distance. Keeping things interesting, the trail is home to a number of outdoor exhibits and educational signage that paints a pictures of the area and its history.

Trail length: 3.5 - 4km (1-2 hours) Highest elevation: 1,212 meters

The Scenic Trail (景觀步道)

If you’re looking for the most Instagram-friendly trail, the ‘Scenic Trail’ is probably the one you’re looking for. This short trail doesn’t take very long to hike and along the mostly flat trail you’ll find a number of Instagram popular installations that have been set up by the park staff and local designers to celebrate the history of the park. Along the way, you’ll also get a pretty good introduction to the natural environment that the rest of the park has to offer.

That being said, if you take a trip all the way to the park and only hike this trail, you’re missing out. If you’re traveling with young children though, it’s a friendly area that won’t tire them out too much.

Trail length: 350 meters (10-20 minutes)

The Forestry Trail (森林知性步道)

Looking at the official park map, the ‘Forestry Trail’ is more or less a trail that combines a number of smaller trails. Hiking this one allows you to experience the natural beauty of the park, while also allowing you to experience the re-forestation efforts that have taken place to help the natural environment come back to life in the areas where the logging industry did the most damage. Passing by the ‘Scenic Trail’ mentioned above, you’ll make your way through the forest covered Father-Son Peaks Trail (親子峰步道), which then loops around and connects with the Forestry Trail (森林知性步道), where you’ll make your way back to the Visitor Center at the end of your hike.

This hike is a much different one than the Self-Guided Trail above in that it doesn’t culminate in a ‘peak’ nor does it offer you scenic views of Taoyuan and New Taipei. The trail essentially just winds its way through a reforested section of the park where the tall Japanese cedar trees and the natural environment that has grown up around them make for some pretty beautiful photos.

Personally this trail was my favorite part of the park as it reminded me of some of the mountainous trails back home in Canada that I would cross-country ski through during my youth.

Trail length: 3km + 1.3km (2 - 2.5 hours) Highest elevation: 1,060 meters

The Dongman Trail (東滿步道)

The longest trail in the park is an interesting one because it is essentially a one-way hike that’ll take the entire day and connects you from one Forest Recreation Park to another. The name “Dongman” (東滿) is a combination of the first characters in “Dongyanshan” (東眼山) and “Manyueyuan” (滿月圓), which is another Forest Park located in Sanxia (三峽). Hikers are free to choose to start the roughly eight kilometer hike in the Forest Park of their choice, depending on personal preference, with one starting at a lower elevation and the other starting at a higher elevation.

The trail is known for its panoramic views of the northern mountain range, but is considered an advanced hike, and should always be done in a group for safety. The other thing that you’ll want to keep in mind is that since the hike starts in one park and ends in another, your method of getting there and getting home will be different, so it doesn’t make much sense to drive your car to one, do the hike, and end up stranded in the other.

Fortunately, there are hiking groups like Parkbus that coordinate hikes to the trail and conveniently provide drop off at one park and pick up at the other, solving those logistical problems.

Trail length: 8km (4-5 hours one way) Highest elevation: 1,130 meters

Park Admission Fees

It is somewhat uncommon for popular tourist destinations to charge an admission fee in Taiwan, but in this case for the purpose of maintaining the quality of the trails, the administration of the park, and most importantly the reforestation effort, a modest admission fee is collected at the entrance.

The current admission fee scheme is as follows:

Weekdays: Adults NT$80

Weekends & National Holidays: Adults NT$100

Group Rate (20 or more people): NT$80

Children: NT$10 (3-6 years), NT$50 (7-12 years)

Seniors (65+): NT$10

Parking Fee: Cars NT$100, Scooters NT$20

Getting There

Address: No.30, Jiazhi, Fuxing Dist., Taoyuan City (桃園市復興區霞雲村佳志35號)

GPS: 121.41761, 24.825110

Car / Scooter

If you have your own means of transportation, getting to Dongyanshan Forest Park is relatively straight forward. Located along the Northern Cross-Island Highway (北部橫貫公路), otherwise known as Highway 7 (台7線), you can make your way to the road from Taoyuan, passing through Daxi (大溪) and Cihu (慈湖) or from New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽區). Even though the Cross-Island Highway is considered a ‘highway’ it’s not an expressway, so scooters and motorcycles are permitted to ride up and down the mountainous road.

Input the address or the coordinates provided above into your GPS or Google Maps and you’ll have the best route conveniently mapped out for you.

It’s important to note though that if you’re driving a car or a scooter (or a Gogoro), the last gas station (and battery swapping station) is located on the turn off to Jiaobanshan Villa (角板山公園), so you may want to fill up before you head to the park. It’s also your last chance to pick up some hiking snacks as there is a convenience store next to the gas station.

Public Transportation

Currently, the only option for taking public transportation to Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Park is to take a bus from the Daxi Bus Station (桃園客運大溪總站). Service is provided by the Taiwan Tourist Shuttle Service (台灣好行) on Route #506, but travelers need to keep in mind that during the week there are only three shuttle services a day and five on weekends and holidays.

It is important that you plan your trip wisely and make sure that you don’t miss the bus, otherwise you might find yourself stranded and waiting around for quite some time.

Weekday departures from Daxi: 8:00, 11:00, 15:00

Weekend departures from Daxi: 8:00, 9:00, 11:00, 14:30, 15:00

Weekday departures from Dongyanshan: 9:30, 13:00, 17:00

Weekday departures from Dongyanshan: 9:30, 12:00, 13:00, 16:30, 17:00

Link: Taiwan Tourist Shuttle Service #506 Dongyanshan Route Timetable (台灣好行)

The fare for the bus is NT$81 each way, or you can purchase a one day pass for NT$150 that’ll cover your trip there and your return trip for a discounted price.

Finally, if you’ve taken the effort to visit Dongyanshan, you’re in luck, because there are a number of other tourist destinations in the area that are also worthy of your time - You’ll find the Jiaobanshan Park (角板山公園), Xiao Wulai Waterfall (小烏來瀑布), Xinxikou Suspension Bridge (新溪口吊橋), Yixing Suspension Bridge (義興吊橋), Daxi Old Tea Factory (大溪老茶廠), Sanmin Bat Cave (三民蝙蝠洞), TUBA Church (基國派老教堂), Cihu Mausoleum (慈湖陵寢), Daxi Old Street (大溪老街), and Sanxia Old Street (三峽老街) all in close proximity to the park.

It doesn’t really matter if you’re visiting to check out some of the trails, or you’re one of those adventurous types making your way along the Dongman Trail. The great thing about a visit to Dongyanshan is that you’re provided access to some of Taiwan’s alpine natural beauty within a short distance from Taipei.

Each of the trails within the park offers stunning views, which are comparable to what some of us from North America are used to, but with the mixture of tropical vegetation at the same time. With beautiful cedar trees, thick vegetation and a variety of indigenous species like Formosan Rock Macaques and a wide variety of birds, the park has something for people of all ages and hiking abilities.

References

東眼山國家森林遊樂區 (台灣山林悠遊網)

東眼山國家森林遊樂區 (Wiki)

東眼山自導式步道 (健行筆記)

東眼山森林遊樂區 (桃園觀光導覽網)

國家森林遊樂區 (Wiki)

東眼山國家森林遊樂區.東滿步道 (Tony的自然人文旅記)

東眼山步道攻略|攻頂小百岳,享受舒服的森林浴 (不一樣的旅人)

健行一日遊 走讀桃園東眼山,淺山卻有高山的感覺 (微笑台灣)

Dongyanshan Forest Recreation Area (Forestry Bureau)

Dongyanshan (Taiwan Outdoors)