Whenever you see travel articles about Taiwan, you’re likely to see the same themes mentioned over and over again - This country prides itself on its culinary prowess, its beautiful landscapes, the friendliness of its people and of course the thousands of 7-11s and ornate temples that line the streets of this tiny island nation.

When it comes to promoting Taiwan to the outside world, the food and the friendliness of the people of this country are often good enough reasons to attract a bit of attention.

There is however a lot more to this country than friendliness and food but you’ll rarely find much else in terms of in-depth articles from official sources or the Taiwanese media which markets the country to both domestic and international tourists in the same way.

For travellers who only have a short time to visit the country, there is a wealth of things to do here that cater to particular interests and hobbies.

Unfortunately the biggest problem is that information for a lot of these places isn’t readily available or even useful when it is.

As the government aims to promote tourism and attract more foreign visitors than ever before, these issues will eventually have to be solved to help make travelling here much easier for the average non-Chinese speaking visitor.

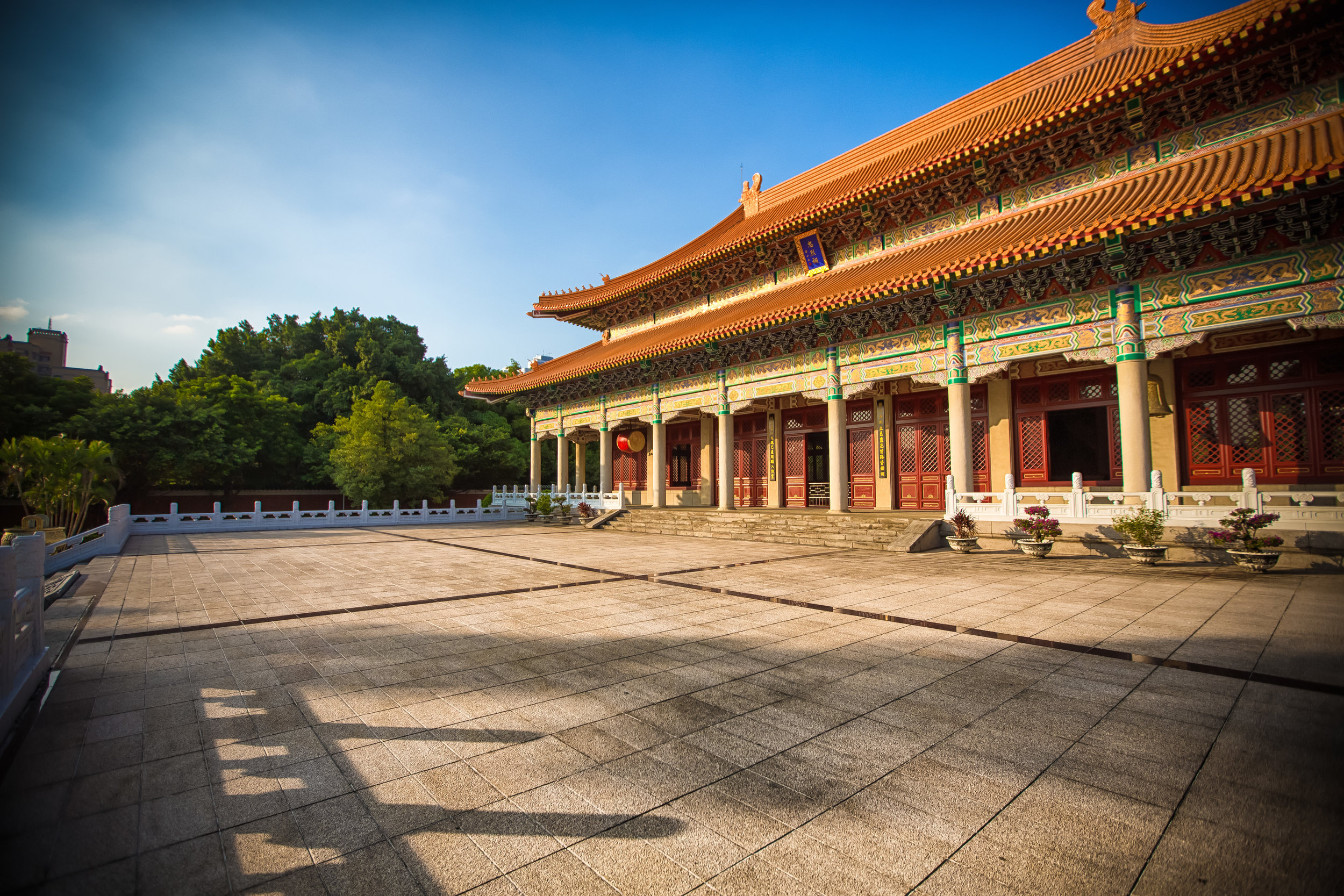

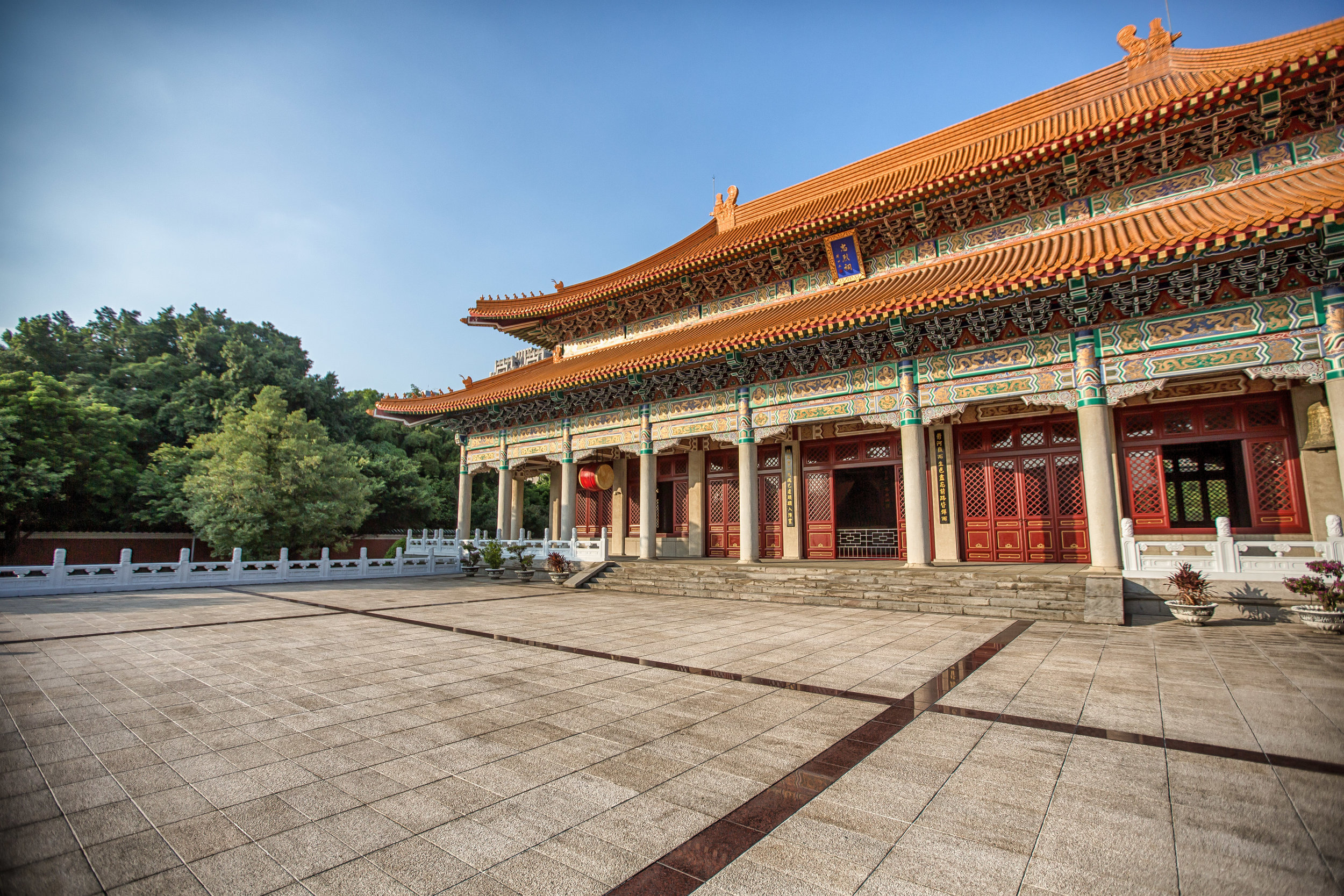

When I first arrived in Taiwan, one of the first things that caught my attention was the ornate temples that are found throughout the country.

Longshan Temple, Xing-Tian Temple and the Xiahai City God temple for example have all been promoted really well and each of them attract hundreds of thousands of tourists every year. This made learning about the temples really easy. When it came to the other temples however, I had to spend a considerable amount of time researching their history to learn about them.

So even though those three are beautiful examples of Taiwanese temple architecture and design with interesting histories, you might be surprised to find out that you can easily find larger, older and more beautiful temples in other parts of the country which pretty much receive little-to-no attention from foreign tourists.

Some might argue that not all of these historic temples want thousands of foreign tourists invading each and every day while others might insist that it would be extremely difficult to promote all of these temples to foreign travellers, but that’s not the point.

No one expects an article about all of these places, but one would hope that the situation continues to improve so that people can make much more informed decisions while visiting.

Today’s post is about one of Taipei’s under-appreciated temples which is situated only a short walk away from the popular Beitou Hot Spring resort area.

It would only make sense that this century-old Japanese Colonial Era temple, one of the few left remaining in Taiwan, be promoted to tourists who are visiting the area but so far it remains somewhat of a secret despite some vague signage.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the last year searching for the remnants of Taiwan’s Japanese Colonial Era to learn their history and take photos.

This particular temple was on my list of places to visit for quite a while but when I finished my research about Taipei’s Huguo Rinzai Temple (臨濟護國戰寺) and realized the historic relation of the two buildings, I decided to make a visit to Beitou’s Puji Temple (普濟寺) as soon as I could find a free day with some agreeable weather!

History - Japanese Buddhism in Taiwan

The ‘Japanese Colonial Era’ (日治時代) began on April 17th 1895 when representatives from the Qing signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki (下関条約) which signalled the end of the first Sino-Japanese War. The treaty, which is still a sour point in Sino-Japanese relations today forced the Qing empire to cede both territory and copious amounts of cash to the Japanese Empire.

When the Colonial Era started, the Japanese were quick to take care of any opposition to their control and also wasted no time in their effort to develop the island with modern infrastructure and also put systems in place to create a thriving economy that would contribute to the Japanese.

As Taiwan was considered to be an important part of the empire, both strategically and economically, the Japanese took special effort to construct buildings of Japanese cultural influence while at the same time building schools, banks, roads, etc.

The buildings of Japanese cultural origin which include the various Martial Arts Halls (武德殿), Shinto Shrines and Buddhist temples, etc. were constructed with the sole intention of helping to ‘convert’ the people of Taiwan into loyal citizens of the Japanese empire. The goal was ultimately to have an island of people who were Japanese in everything but ancestry.

Buddhism, having established a foothold on the island several centuries earlier was one of the tools that the Japanese used to help bring the two peoples together. Initially, the Japanese brought Buddhist monks with them to serve roles in the military as chaplain-missionaries offering spiritual guidance during the initial years of the occupation.

The monks who came to Taiwan eventually began to construct language schools and charity hospitals where they would focus on improving the lives of average Taiwanese citizens as well as promoting Japanese-style Buddhism. This effort didn’t last long however thanks to the language barrier and the fact that Japanese Buddhism was viewed by the locals as a colonial system of beliefs which only benefitted the colonial power.

The lack of results in terms of cultural conversion led to funding ultimately being cut off by the Japanese central government and forced the monks who had come to Taiwan to focus less on the native population and more so on the benevolence of the Japanese people who migrated to the island.

Despite Buddhism being a tool used by the Japanese to help endear the people of Taiwan to their new colonial rulers, the religion had taken a major hit in both its support and its funding within Japan thanks to the Meiji Restoration (明治維新).

The restoration which started in 1868 sought to modernize and reform the country and focused its efforts on aspects of society which were deemed to be ‘feudalistic’ or ‘foreign.’ Buddhism, despite its immense importance to the development of Japanese culture was a religion from outside of Japan and was thus viewed as inferior to state Shintoism.

Interestingly, even though Buddhism was originally used as a way for the colonial powers to endear themselves to the people living in Taiwan, the religion ultimately became a tool for the people of Taiwan to use in an attempt to brush shoulders with the higher-ups in Japanese society to gain political or economic favour and also to use religion as a cover for activities that the colonial powers might frown upon.

Today, most people in Taiwan, if asked would say that they are Buddhist. The history of Buddhism in Taiwan is a long and confusing one and despite the religion being a tool for state control (for both the Japanese and the Chinese Nationalists) the legacy of the Japanese Colonial Era can still be felt today as most of the largest Buddhist organizations operating in Taiwan today adhere to the philosophy and practices of the schools of Buddhism brought to Taiwan by the Japanese.

Puji Temple (普濟寺)

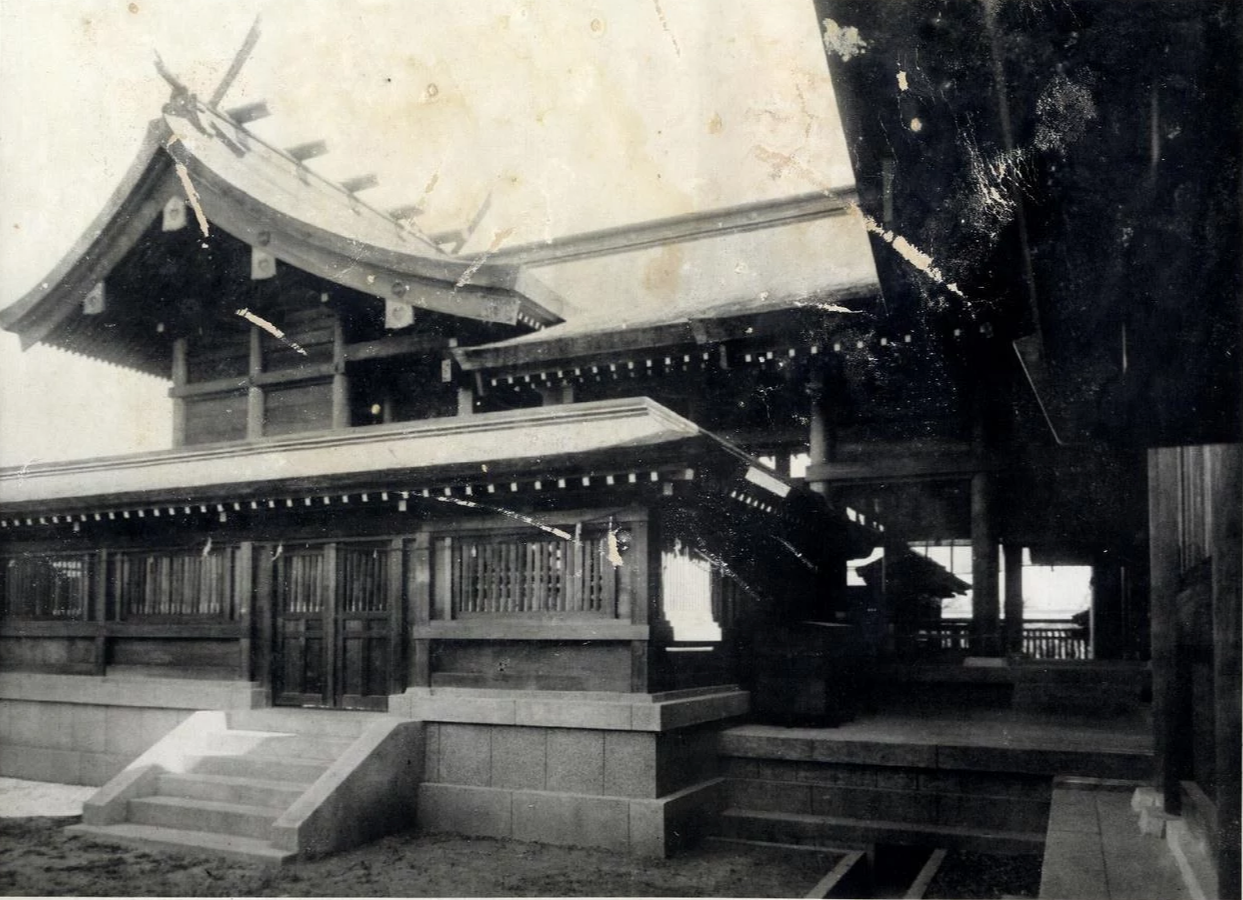

The relatively unknown Puji Temple, one of the few remaining Japanese-style temples in Taiwan today sits quietly on a hill above the popular hot spring resort area in Taipei City’s Beitou District (北投區). The temple, which dates back to 1905 (明治38年) is now over 110 years old and is considered one of Taipei’s most important historic sites.

The temple, which was originally named “Tetsu’shinin Temple” (鐵鎮院) was constructed with funds donated by Japanese railway workers and engineers who wanted to celebrate the completion of the project with a newly built temple.

The (now defunct) Tamsui Rail Line (淡水線) was completed in 1901 and followed pretty much the same route as Taipei’s Danshui MRT Line (淡水信義線) today. When the rail line was completed it provided service between Tamsui and Taipei as well having a special off-shoot line of the railway which transported tourists between (the former) Beitou Railway Station (北投車站) and the Xinbeitou Train Station (新北投車站).

Hot Spring culture, known as “Onsen” in Japan has been popular throughout Japanese history, so when the Japanese arrived in Taiwan, they wasted little time developing Beitou, which was then known as Hokutō Village into one of the premiere hot-spring resorts in the empire - one so luxurious that even Prince Hirohito enjoyed a stay!

Puji Temple, which was constructed on a hill above the hot spring resort area belonged to the Shingon school (真言宗) of Buddhism, one of the most history and most widely practiced schools of Buddhism in Japan, founded by Kōbō-Daishi (弘法大師), one of the most prolific figures in the history of Japanese Buddhism.

Note: Kōbō-Daishi has appeared on my blog before @ Taipei Mazu Temple

The temple which was constructed with traditional Japanese architecture and beautiful Hinoki cypress is extremely well-preserved and is one of the finest examples of Japanese temple architecture in Taipei today. The small temple, which has only been renovated once since its original construction maintains the original design.

The roof of the main hall features a typical Japanese swallow-tail or hip-and-gable roof in its original state and still in excellent condition. The roof has yet to be restored, so the tiles on the top have faded in colour from the original black but despite their age are still quite impressive.

One of the most important things to notice on the exterior of the temple are the bell-shaped windows on either side of the main entrance which are known as katōmado (火灯窓) and are common in Japanese temples, shrines and even in castles built after the sixteenth century but rare here in Taiwan.

The interior of the temple itself hasn’t changed much in the years since the end of the colonial era - the interior design remains the same and the religious ceremonies that are held within still adhere to the original Japanese way of worship. The interior is almost perfectly square in dimensions and when you enter there is an elevated area covered in tatami mats where people sit to meditate. The wooden beams on the ceiling and to the sides are all large single-piece hinoki cypress and even today a century after the temple was finished still smell amazing.

If you have a keen eye, you’ll notice that the two bells to the sides of the entrance are not the originals and are only about 30-40 years old evidenced by the ROC era dates (民國) on the side. I asked the monk who was at the temple what happened to the original bells but he didn’t have any idea and was surprised to find out that the bells in the room weren’t actually the originals.

The temple’s main shrine is dedicated to Guanyin (觀音菩薩) but interestingly the Guanyin that is worshipped inside is a bit different than the typical Guanyin that you’ll find in other areas around Taiwan. This Buddha is a special one that is known as the ‘Protector Deity of Hot Springs’ (湯守觀音) and sits cleverly above the hot springs resort protecting the people who come to visit.

When the Japanese Colonial Era ended in 1945, ownership of the temple transferred to a new Buddhist association which then in turn changed the name to Puji Temple. Initially the temple was used by Tibetan lamas who escaped to Taiwan with the Chinese Nationalists. The temple was then later transferred to the ownership of the same Rinzai Buddhist association who control the beautiful Huguo Rinzai Temple (臨濟護國戰寺) in Taipei.

Today the temple sits peacefully and somewhat secretly on a hill above the popular hot-spring resort area. There are signs that lead tourists to the temple, but it seems like most of them are unclear and without the aid of Google Maps, I would have had a hard time finding it myself. The relative seclusion and the beautiful view of Datun Mountain (大屯山) from the front entrance however make for a zen-like experience.

For tourists there isn’t a whole lot to see when you visit this beautiful temple - you don’t need a lot of time but if you are interested in Taiwan’s history, a quick visit to this century-old temple should be able to shed a little bit of light on a period of Taiwan’s history that is quickly disappearing as time goes by.

Getting There

Getting to Puji Temple is quite easy if you are visiting Taipei's Beitou District - Simply take the MRT to Xinbeitou Station (新北投站) and when you exit, walk up either side of the road that takes you to the Hot Spring resort area. You'll see signage along the way that will lead you to the temple. It is a short ten minute walk from the MRT station and is very close to Beitou's Thermal Valley which is also a pretty popular spot for tourists.

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Shots)