Winter is often a miserable time of year for those of us living here in the north of Taiwan. The weather becomes a bit chilly, it rains non-stop and the humidity makes it feel like you’re constantly dripping.

Luckily though, Taiwan’s natural environment provides for a bit of respite from the cold, damp weather in the form of volcanic hot springs which are abundant in places like Wulai (烏來), Jiaoxi (礁溪) and Taipei’s very own Yangmingshan (陽明山) where the people of this country can enjoy a relaxing dip in geothermally heated pools of water that are thought to have therapeutic uses that help with anything from chronic fatigue to soothing to pain of arthritis.

When the Japanese took control of Taiwan, they brought with them a rich and well-developed Hot Spring (onsen) culture and sought to develop Taiwan’s various hot spring locations into popular destinations for rest and relaxation.

Taiwan’s first hot spring hotel opened in Taipei’s Beitou district (北投區) in 1896 only a year after the Japanese took control of the island and from that time on the Japanese love of hot springs has became an inseparable link between the two nations.

Beitou (北投)

The Beitou area of Taipei has since been developed as a resort destination for the people of Taipei with public and private baths, hotels, tea houses and parks set up to cater to visitors. In the past all visitors had to do was take a train from the city to get to the resort, but today it is much more convenient as Beitou (北投站) and Xinbeitou stations (新北投車站) are connected to the popular Taipei Metro System.

If you are travelling to Beitou during the winter or on a weekend, it is important to remember that the Hot Springs resort area is extremely popular and if you are wanting to find a private space in a hotel, it is best to reserve your time ahead of your visit to ensure that space is available.

If you aren’t shy and prefer to save some money, you should probably consider taking the public bath option where you’ll be able to enjoy hot spring culture at its finest. It’s important to remember that each of the public baths may have different etiquette and rules with regard to gender separation and whether or not you’re permitted to wear clothing in the water.

While Hot Springs are the main attraction for visitors to Beitou, there is also quite a bit for people to do when visiting apart from taking a bath. The area has coffee shops, parks, museums, temples and great food as well.

If you are visiting you may want to consider checking out some of the historic Japanese buildings left over from the Colonial Era - The Beitou Hot Springs Museum (北投溫泉博物館) is one of the best examples of modern architecture of that era while Puji Temple (普濟寺) and the Plum Garden (梅庭) are much more traditional.

While visiting the area you may also want to consider checking out some of the museums, which include the Hot Spring Museum, the recently reconstructed Japanese-era Beitou Train Station, the Ketagalan Culture Center (凱達格蘭文化館) or the Taiwan Folk Arts Museum.

One of the coolest attractions however is the Beitou Thermal Valley or “Hell Valley” (地熱谷) which is a short walk away from the resort area and puts on display the awesome power of the natural environment in a way that you may not have ever seen before.

Thermal Valley (地熱谷)

If you are visiting Beitou to take in some Hot Springs, a visit to the Thermal Valley is one of those things that you absolutely have to do in order to really appreciate the awesome power of the geothermal springs in the area.

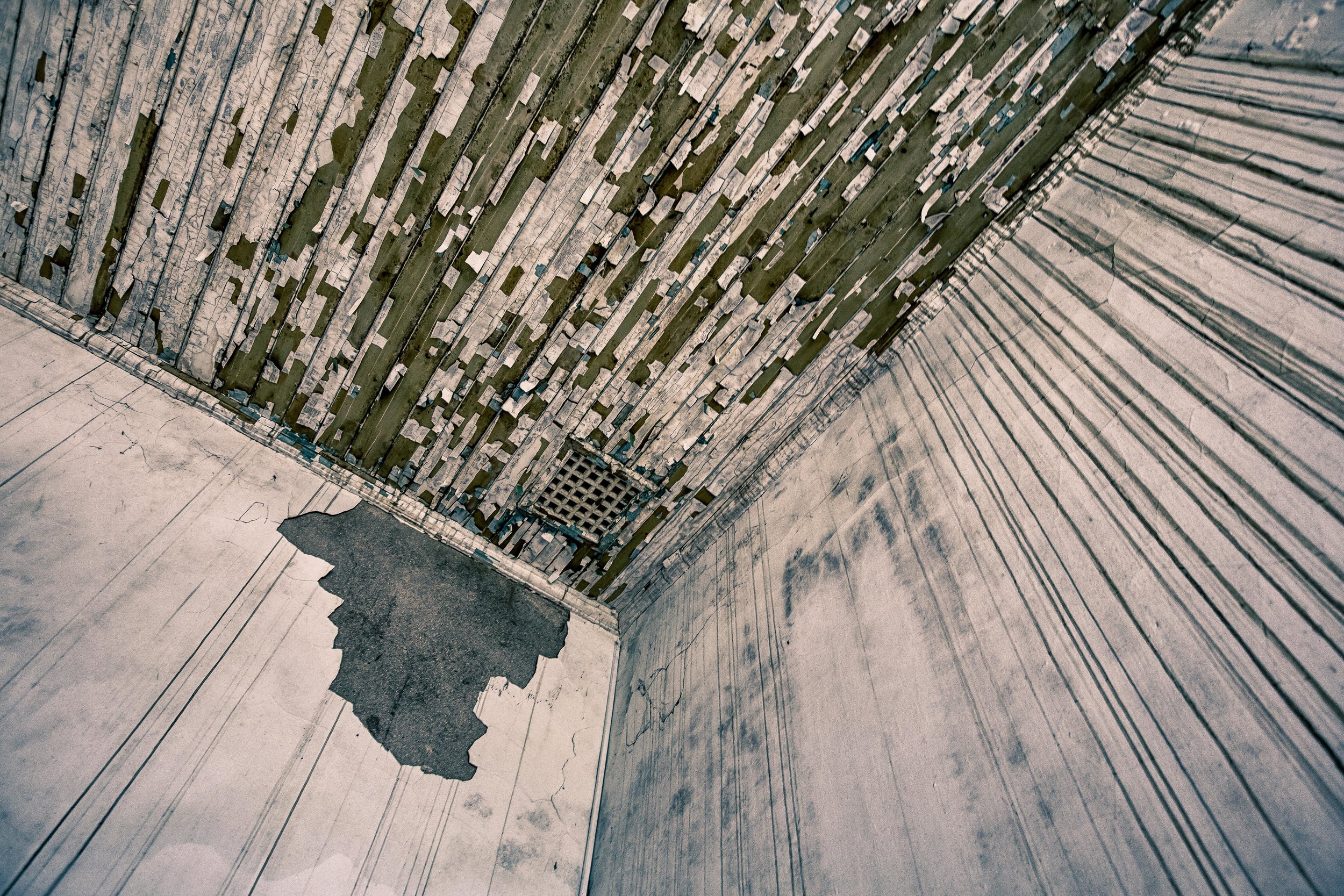

The Beitou Thermal Valley, otherwise known as “Hell Valley” (地熱谷) in Chinese is a small nature park that is free of charge for visitors and consists solely of a small lake with a fenced off walkway (for your safety). You may not think that sounds very interesting, but the lake is the main attraction and is one of the primary sources of hot spring water for the resort area.

The main attraction of the lake apart from the emerald green colour of the water is probably that of the year-round sulphuric steam that rises up from the water and blankets the valley in a haze of extremely humid fog. If you are visiting during the hot Taiwan summer days, prepare to sweat buckets while walking along the path.

The temperature of the water in the lake varies between 80-100℃ and is considered to be the hottest of any of the hot spring sources in the Datunshan Volcano Group (大屯火山群). The water itself isn’t your typical H2O and contains a number of additional chemical elements, most notably the sodium carbonate which is corrosive (that’s why there are protective barriers) and gives the spring water its beautiful green colour.

In the past, people would bring eggs to the valley to boil them in the hot spring water - Today hard-boiled hot spring eggs (溫泉蛋) are still popular with the people of Taiwan, but for safety reasons it is now prohibited to boil eggs or get close to the water at the Thermal Valley. You can however buy some ‘hot-spring eggs’ at a stop near the entrance of the park, which is highly recommended if you’re a fan of eggs. I’d also recommend trying the hot-spring ramen restaurant “Mankewu Ramen” (滿客屋拉麵) which is also nearby.

Another interesting aspect of the Thermal Valley are the naturally occurring rocks known as Hokutolite or “Beitou Rocks” (北投石) which are strange-looking calcified rocks that come in many strange-looking shapes and sizes. The rocks contain minute traces of strontium and the radioactive element radium and the Thermal Valley is one of the two places in the world where this occurs naturally which is why the area has been protected for conservation.

With this in mind, don’t try to jump the fence and take a swim in the lake - not only will you be cooked alive, you might also come out breathing fire like Godzilla.

If you are planning a trip to the Beitou area for some hot springs, then a visit to the Thermal Valley is recommended. If you’re not going out to Beitou for any particular reason however, I think its probably not really a worth the long MRT ride if you don’t have anything else planned. If you aren’t going for hot springs, but still want to go check out the valley, I’d recommend including a trip to the beautiful Guandu Temple or the Guandu Marshlands for a bike ride along the river. You could also head out to Danshui to check out the popular tourist street there.

Getting There

The valley is a ten minute walk away from Xinbeitou MRT Station (新北投捷運站) and isn’t far from the Public Baths or any of the private hotels that offer hot springs. When you leave the MRT station simply just walk straight and you’ll arrive after a short walk. The Thermal Springs are also quite close to the historic Puji Temple, so you may want to check that out as well while you’re there.