In the first part of this blog, I introduced the history of the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, its transition into the Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine, and its current transformation into one of Taoyuan’s most popular tourist attractions.

Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine (桃園忠烈祠)

The recent restoration of the shrine and its administrative restructuring has placed a lot more emphasis on the shrine’s history as a Shinto Shrine, with its Japanese characteristics being promoted much more than its most recent history.

With 2020 (and beyond) being plagued by a global pandemic and the closure of international travel, this elegant and historic Japanese Shrine has gained become even more popular as Japan tends to be the number one destination for Taiwanese travelers, who are so obviously missing the opportunity to travel to one of their favorite countries.

This lack of ability to travel to Japan has given locals a new appreciation for the shrines, temples and historic buildings leftover from the Japanese Colonial Era, and people have taken to traveling around Taiwan to enjoy them in massive numbers. The popularity of places like the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine has never been so high, so even though this pandemic has been terrible, it has allowed for a new level of appreciation for what is already available here in Taiwan.

In the first section of this introduction to the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine, I focused on the history of the shrine, while this section is going to offer an in-depth look into the architectural design of the shrine and the various things that you’ll want to take note of when you visit.

So, without further delay, let’s get into it.

The Architectural Design of the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine was built in a strategic location on a hill near the base of Taoyuan's Tiger Head Mountain (虎頭山), overlooking the city. The location chosen for the shrine was significant because larger Prefectural Shrines like this one are typically constructed on hills, preferably mountains, overlooking a town or city, in order to bless its people.

When the shrine was constructed, the large trees and buildings that currently block its view of the river and the city. So when it was first constructed, the shrine would have provided an excellent view of the city which had yet to really develop.

These days, you have to travel much further up the mountain to get a good view of the Taoyuan City skyline. This is why Hutoushan Park (虎頭山公園) has become such a popular destination for people living in the area to enjoy some outdoor recreation with the large open park on the top of the mountain offering some pretty spectacular views of the Taoyuan cityscape.

As I previously mentioned in the first part of this blog, the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine and the layout of the landscape meticulously follow Japanese tradition, offering tourists the opportunity to not only experience a bit of Taiwan’s history, but the feeling that you’ve been transported to Japan, without having to fly out of the country.

Even though the shrine is very much Japanese in its design, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the Hall of Worship, the largest building at the shrine, is an interesting a fusion of styles that blends Japanese and ancient Chinese-style architecture.

As is the case with most of the buildings that were constructed during the colonial era, the shrine was constructed using Taiwan’s famed Alishan cypress (阿里山檜木), one of the most amazingly fragrant, and more importantly, durable varieties of timber that you can find.

As you’re probably already aware, I’ve broken this blog up into two different sections. The first was a look at the history of the Shinto Shrine, which subsequently was converted into a Martyrs Shrine, or a War Memorial for the fallen members of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces. In this section, I’m going to focus on the architectural design of the shrine and each of the important pieces that make it complete.

For clarity sake, I’m breaking up each of these important pieces into their own section so that I can better introduce their purpose and aspects of their design. Some of this information might be considered too in-depth for the average reader, so I’ll try to make it as painless as possible so that you’ll have a better idea of what you’re seeing when you visit the shrine.

The Visiting Path (參道)

The Visiting Path, otherwise known as the “sando” (さんどう) is an important part of the design of any Shinto Shrine and is essentially just a long pathway that leads visitors to the shrine. While these paths serve a functional purpose, they are also quite symbolic in that the “road” is the path that one takes on the road to spiritual purification. Shintoism itself is literally translated as the “Pathway to the Gods” (神道), so having a physical pathway that leads the worshipper from the realm of the profane to that of the sacred is quite important.

Traditionally, the Visiting Path to a Shinto Shrine is lined symmetrically on both sides with Stone Lanterns (石燈籠), known as ‘toro’ (しゃむしょ), but the original lanterns that were constructed for this shrine were all destroyed after the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan.

Today the Visiting Path features six (electrified) lanterns, two large and four small, which were constructed in 1986, when the shrine underwent its first restoration.

The lanterns are placed along the Visiting Path just before you reach the shrine gate and even though they’re only a couple of decades old, it is important that they continue to exist in some form today.

The Visiting Path to the shrine used to be exponentially longer than it is today and would have stretched all the way to the river, but today starts on the hill below the main level of the shrine and continues all the way to the Main Hall. The path starts out quite wide, but as you walk further toward the inner shrine, it becomes considerably more narrow.

The Shrine Gate (鳥居)

The traditional Shrine Gate, otherwise known as a "torii" (とりい) is not a completely foreign object here in Taiwan as you’ll find that most large temples feature a variation. Even though we traditionally associate these gates as iconic images of Japan, the meaning of the gates here in Taiwan, and across Asia remains the same as once you pass through, you are thought to be crossing from the profane world, which is considered to be unclean, to a sacred place.

Although we commonly associate these gates with Japan, as I just mentioned, variations can be found throughout Asia at places of worship. The “paifang” (牌坊) gates of China and the “Hongsalmun” (홍살문) gates of Korea are just a few examples.

In Japan, the presence of one (or more) of these gates is one of the simplest ways of identifying that there is a shrine nearby and also one of the best ways to know that you’re approaching a Shinto Shrine rather than a Buddhist temple.

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine was originally home to five of these sacred gates, which stretched from the shrine all the way to the river along the Visiting Path. Unfortunately all of them, known as the first gate (一の鳥居) to the fifth gate (五の鳥居) have been torn down.

The lower gates, which were located along the extended visiting path mentioned above were demolished when Taoyuan was going through the process of widening roads and developing new communities in the area between the shrine and the river.

Currently there is only one gate at the shrine, but you might notice that it is architecturally different from what you’d see in Japan - This is because when the shrine was restored in 1986 (民國75年), the people in charge of the project wanted to have a sacred gate, but didn’t want it to resemble exactly what you’d commonly find at Shinto Shrines in Japan.

The original gates were all constructed with wood and would have had sacred ropes known as shimenawa (標縄) hanging from them, but this one was constructed using concrete and features only a single layer, rather than two.

Nevertheless, there is a still a certain to beauty to its simplicity.

The Purification Fountain (手水舍)

An important aspect of Shintoism is something known as “hare and ke” (ハレとケ), otherwise known as the "sacred-profane dichotomy." It is thought that once you pass through the shrine gate, which is considered the barrier between the ‘profane’ and the ‘sacred’, it is necessary to do so in the cleanest possible manner by symbolically purifying yourself at the chozuya (ちょうずしゃ) or temizuya (てみずしゃ) provided.

An absolute must at every Shinto Shrine, the purification fountain is an important tool for symbolically readying yourself for entrance into the sacred realm. To do so, worshippers take part in a symbolic ritual that it’s safe to say that every person in Japan is familiar with.

To purify yourself you should follow these steps:

Pick up a ladle with your right hand.

Scoop some water from the fountain

Purify the left hand.

Purify the right hand.

Pour some water in your left hand and put it in your mouth.

Bend over and (cover your mouth as you) spit the water on the ground.

Purify the handle of the ladle and then lay the dipper face down for the next person to use.

Link: How to Perform the “Temizu” Ritual (Youtube)

If you’re visiting a Shinto Shrine and aren’t entirely aware of the process, never fear, most shrines will have a set of instructions available for guests.

The Purification Fountain at the Taoyuan Shrine is one of the most architecturally significant pieces of the shrine as no effort was spared on the construction of the beautiful pavilion that covers the fountain.

The arched kirizuma-zukuri-style (切妻造) hip-and-gable roof is absolutely beautiful and is one of those architectural styles that shows off the mastery of Japanese craftsmanship.

The shape of the roof is likened to that of an open book that is placed face down with a high arch and two sides that slope down. The roof was constructed with cypress and is simply yet beautifully decorated with carved hanging fish and copper onigawara (鬼瓦) ghost boards and birds on both sides.

The roof is supported by four thick wooden pillars, which help to stabilize the pavilion and are assisted by an expertly crafted network of trusses, allowing the pillars to distribute the weight of the roof and ensuring that it doesn’t collapse.

The double-layered concrete fountain is about 180cm in length and 80cm high and has been recently upgraded with sensors that turn on the water when someone approaches in order to help save water. The lower layer of the fountain doesn’t have any water, but is the area where worshippers are meant to spit the water that they’ve used to purify themselves.

The top layer sits within the lower layer and has a wooden bar running across the mid-section that allows people to place their ladles. The design of the fountain itself is simple, but elegant.

As a whole, the Purification Fountain is one of the highlights of the entire shrine and even though it might not appear to be very important, I highly recommend you take some time to examine the craftsmanship that went into its construction.

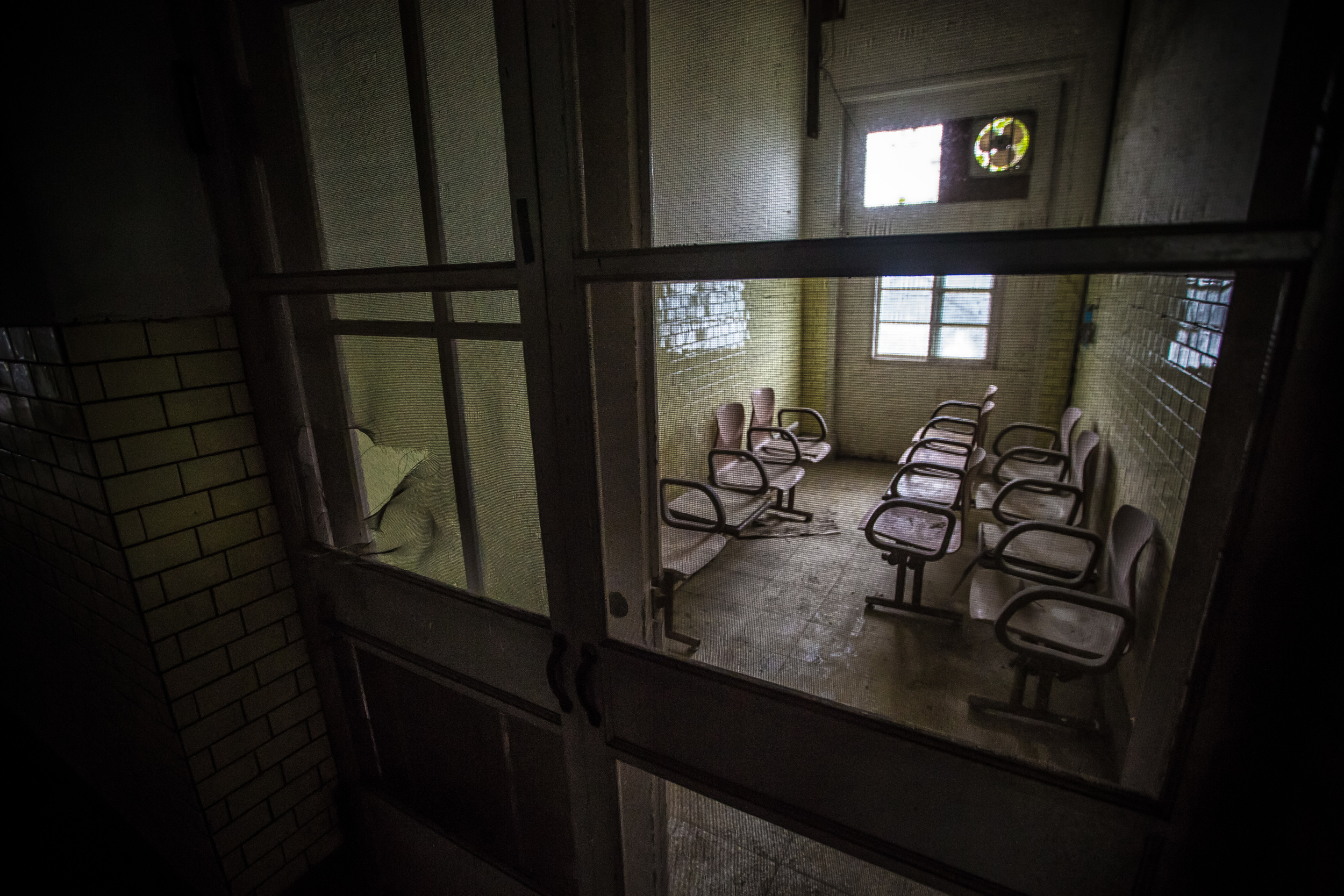

Administration Office (社務所)

The shrine’s Administration Office, otherwise known as a shamusho (しゃむしょ) is located to the right of the shrine gate and is directly opposite the Purification Fountain.

This is where the day-to-day affairs of the shrine’s management were conducted as well as where visitors could purchase shinsatsu (神札), or good luck charms.

The interior a couple of large rooms with floors covered by tatami mats and were used as an office for the shrine as well as providing space for religious ceremonies or functions.

Constructed with a fusion of Japanese and Western techniques, the building was built primarily with Taiwanese cypress, but has a concrete base to help protect the building from both earthquakes and termites.

Unlike the other buildings at the shrine, the office has a simply designed roof that features black roof tiles (黑瓦), which are quite common in Japanese residential buildings. One of the most architecturally significant aspects of the building and its roof is its covered front porch, which is known as a karahafu door (唐破風).

This style of design is indicative of Japanese architecture dating back to the Heian Period (平安時代) from 794-1185. These so-called porches, extend from the front of the building and have pillars holding up a roof that is separate from the rest of the building.

This style of design is a common architectural characteristic found in Japanese castles, temples, and shrines and makes the building stand out considerably more thanks to its addition.

In the past the building was open to visitors and featured exhibitions about the shrine and local history, but it currently serves the administrative office for the caretakers of the shrine and the security guards who help to protect it from vandalism.

I’m not entirely sure if there are future plans to open the building back up to the public or just transfer the exhibition spaces to the former dormitories to the rear of the building. The literature online seems to point to it eventually being used as an exhibition space, but so far it doesn’t seem like they’re ready for that yet.

The recent restoration project that took place between 2019 and 2020 saw the addition and restoration of a beautiful veranda attached to the sides and rear of the building. Visitors are now able to sit down and relax under the cover of the trees, which were planted when the shrine was constructed more than eighty years ago.

The Stone Lions and Bronze Horse (高麗犬 / 神馬)

As you walk up the Visiting Path towards the set of stairs that brings you to the Middle Gate, you’ll encounter three important objects that are important for every Shinto Shrine, the Stone Lion Dogs and the Bronze Horse, each of which perform important functions for the shrine.

First, the Sacred Horse, otherwise known as a “shinme” (神馬 / しんめ) is regarded as the sacred mount of the kami enshrined within the shrine and you’ll often find two of these horses at most large shrines. The addition of these horses is an ancient Japanese custom that started during the Nara Period (奈良時代) from 710 to 794 AD, where live horses would be dedicated to the kami within a shrine. However due to the difficulty and expense of raising horses, they were eventually replaced with these bronze versions.

The Sacred Horse at the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine is 205cm in height and 270cm long and is quite majestic in its craftsmanship. There is however a bit of a mystery about the origin of this horse as it doesn’t actually appear to be the original horse used by the Taoyuan Shrine.

One of the ways to tell this is to look at the emblem (神紋) found on the belly of the horse, which should be the same emblem used to identity the shrine. In the case of the horse that exists at the shrine today, it features a fifteen-petal chrysanthemum (15瓣菊) on the outside with what looks like a five-petal lisianthus flower (桔梗花) on the inside.

Considering the official emblem for the former Zhongli Shinto Shrine (中壢神社 / ちゅうれきじんじゃ) was the same, it is safe to assume that the horse came from that shrine. Although, I’m not really too sure about that because the site of the original shrine, which is now home to Zhongli Senior High School (中壢高中) has one of the horses on display, but has a slightly different design and the emblem has since been painted over.

The next set of stone carvings are another absolute requirement for any Shinto Shrine, the famed Lion-Dogs, known in Japan as the komainu (狛犬/こまいぬ).

Tasked with warding off evil spirits, the komainu are the guardians of the shrine and can be found guarding either the entrance of a shrine by the Shrine Gate or further inside.

Similar to the stone lions that act as temple guardians at other temples in Taiwan, the word “komainu” translates as “Korean Dog” (高麗犬), referring to the ancient Korean Kingdom of “Koguryo” (高麗國), where it is thought that the tradition was passed on to Japan.

Although there are exceptions to the rule, komainu usually appear as a pair and are placed on either side of a visiting path or at the entrance to a shrine. Often appearing as a male and female, the komainu are only distinguishable only by their facial expressions, with the male “a-gyo” (阿型) having an open mouth and the female “un-gyo” (吽形) having a closed mouth.

Link: Komainu Lion Dogs (Japan Visitor)

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine was originally home to two pairs of komainu guardians, however when the colonial era ended and the shrine was converted into a Martyrs Shrine, they were likely destroyed. The set of stone guardians that we can see today are reproductions that date back to the first restoration of the shrine in 1986 (民國75年).

Even though they mimic the original design, just like the Shrine Gate, certain design elements were left out as to not make them entirely ‘Japanese’.

The set of komainu currently sit along the Visiting Path on the hill between the Middle Gate and the Shrine Gate and even though they aren’t the original guardians of the shrine, they are nonetheless tasked with the important job of keeping this national historic treasure safe.

The Middle Gate (中門)

Once you’ve climbed up the stairs and passed by the stone lion-dogs, you’ll have reached the Middle Gate, known as the “chumon” (中門 / ちゅうもん).

Oddly, most of the articles and research papers that talk about the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine don’t really spend much time talking about this beautiful gate. It is after all just a gate that opens up to the most important part of the shrine, the inner sanctum. If you ask me though, this gate is one of the most important and aesthetically pleasing aspects of this shrine.

The elegant carpentry and detailed craftsmanship it took to construct it deserves more respect.

The gate is part of a beautifully designed wooden fence that has been constructed to surround the perimeter of the Hall of Worship and the Main Hall to keep people from breaking into the shrine.

The fence is beautifully designed using Taiwanese cypress and the craftsmanship put on display with the simple, yet beautiful decorations deserves your attention.

On top of the gate you’ll find a ridged roof similar to that of the gate, and is in a style that makes it difficult to climb over.

At first, it seemed that the gate was designed as a fusion of the “karamon” (唐門) style entrance, which is characterized by its usage of an extended karahafu porch, like the one that was used on the Administrative Office above.

The roof here though differs from that style in that it utilizes a similar kirizuma-zukuri (切妻造) style of design, like the one that was used on the roof of the Purification Fountain below. After some digging, I discovered that the gate is actually a variation on the hakkyakumon gate (八脚門 / やつあしもん), a style that dates back to the Nara Period.

In this style, you’ll find four vertical pillars on the front and back that support another four horizontal pillars at the base of the roof. Even though it may not appear so complex, you have to realize that these things have all been constructed without the help of nails or screws, which means that the network of pillars and trusses have all been expertly fit to ensure that the gate is snug and won’t collapse under the weight of the roof.

If my description didn’t impress you enough, check out the link before which has detailed graphics that describe the stages of construction on the roof. The mathematical genius it takes to build these things is jaw-dropping.

Link: 八腳門 (鎌倉の古建築)

As you climb the hill towards the gate, the roof appears to be flat, but it is ridged to look like an open-book. The shape becomes much more noticeable as you look back at it from the steps of the Hall of Worship.

The front of the gate is home to a plaque that reads “The Soul of the Country” (國魂), which was added when the Shinto Shrine became a Martyrs Shrine. Given the shine’s current usage as a war memorial for the Republic of China’s Armed Forces, the plaque featuring a phrase like this shouldn’t really be much of a surprise.

If you are visiting the shrine on a sunny day, the cypress gate seems to bask in the sunlight and the light you get coming through he trees makes the gate appear almost as if it’s glowing.

As an important aspect of Shinto is harmony and blending into nature, I’m sure you’ll be able to appreciate how much thought went into the design of this gate.

The Hall of Worship (拜殿)

The Hall of Worship is by far the main attraction of the shrine.

Known in Japan as the “haiden” (拜殿 /はいでん), for the vast majority of worshippers, it is the spiritual heart of the shrine and given its importance, it is the building at the shrine and as well as the most architecturally distinct.

Even though it has never actually been officially confirmed, one of the most likely reasons that the Taoyuan Shrine has been able to outlive so many of its contemporaries around Taiwan is due to the fact that it was constructed with a fusion style of architecture, combining Japanese elements with the style of architecture that of China’s Tang Dynasty (唐朝).

So it doesn’t particularly matter if you’re Japanese or Chinese, when you look at this building, you’ll easily be able to find architectural elements from both cultures.

That being said, much of the traditional architecture in Japan, Korea and Vietnam takes inspiration from the Tang Dynasty, which was one of China’s most influential periods of artistic and cultural achievement.

Link: Architecture during the Tang Dynasty (Boundless)

Constructed in the shape of a “T”, the interior of the building features a large worship room with wings connected on both the eastern and the western sides. Save for the concrete base that elevates the building off of the ground, the Hall of Worship was constructed primarily with Taiwanese cypress, and just like the other buildings at the shrine relies on a network of pillars on the front and back of the building to support the weight of the massive roof.

And what a roof it is..

This traditionally designed irimoya-zukuri roof (入母造 / いりもやづくり) is one of the first things that you’ll notice as you make your way to the top of the hill and get your first look through the doors of the Middle Gate. The Japanese-style ‘hip-and-gable’ roof looks almost three-dimensional in its design and the flowing lines along its many ridges, make it seem like its actually moving.

In most cases when a new building is being designed, you would tend to think that the interior would be your primary inspiration. The design and the construction of the wooden base of this building however, was crafted solely to bring out the brilliance of the roof. This is because according to traditional Japanese design, buildings that have magnificent roofs like this one are held in high esteem, which is why they’re generally reserved for shrines and castles.

It shouldn’t be much of a surprise that when this shrine was being planned, the roof was the key design feature, while the base itself was kept relatively simple.

While preparing to write this blog, I ended up discovering that explaining the shape of the roof in detail in English was going to be rather difficult. So, in an attempt to not confuse everyone, I’m including some diagrams of the building below to better illustrate the various sections of the roof so that you can understand why its so special.

Before we start, here are a few important words to learn:

Moya (母屋) - Literally, “Mother House”, the lower core of the building.

Irimoya-zukuri (入母造) - A combination of the two styles of roof below.

Kirizuma-zukuri (切妻造) - A style that uses a long-extending curved front slope (gable).

Yosemune-zukuri (寄棟造) - A style that uses four sloping faces (hip)

The key thing that you’ll want to remember about this style of roof is that when we refer to it as a ‘hip-and-gable’ roof in English, that doesn’t really give you a full understanding of the complexity of this design. What “irimoya” essentially means is that it is a combination of both the ‘kirizuma’ and ‘yosemune’ styles into one roof.

The ‘kirizuma’ part acts as the upper portion of the roof, or the ‘gable’ and has two sides, while the ‘yosemune’ part is the lower part, or the ‘hip’ and has four sides.

Starting with the gable (kirizuma), the first thing you’ll want to notice is that there is a veranda on the front of the building, known as a ‘hisashi’ (廂), which is covered by the sloping roof.

The front section of the gable extends well beyond the ‘moya’, so there is a network of pillars at the front of the shrine that are strategically placed to help support the roof. The gable is constructed to look like the Chinese character “入”, and like the character you’ll notice that one side is much larger than the other and has a larger slope.

When you look at the back side of the gable on the other hand, you’ll find that even though it is considerably smaller than the front, there are the same amount of pillars, which are there to help distribute weight and maintain stability.

The ‘hip’ (yosemune) section of the roof on the other hand has four triangular-shaped sides with sloping faces that rise up to connect to the top of the gable. Looking from the sides, the hip part of the roof on either side of the gable helps to consolidate the three-dimensional aspect of the roof as the four sides seem to rise up out of nowhere, creating a triangular shape that looks as if it is physically pushing the ‘gable’ to its apex.

Likewise, both the eastern and western wings of the building feature their own variations of the same style of roof, but even though they’re lower in height than the main section of the building, they ultimately meet with it to help increase the architectural complexity of the building.

In actuality, both of the wings could have just had simple roofs that cover the building and the network of beams that extend from the main building, but that just wouldn’t be the way these things are done. Everything has to be intricate and the attention to detail has to be beautiful.

Link: 台灣日式建築的屋瓦 (空間母語文化藝術基金會)

Speaking of beauty, let’s move on to the decorative aspects of the roof.

The roof is covered entirely with flat copper tiles (平瓦) and features ‘onigawara’ demon tiles (鬼瓦) at the two edges of the ridge, ‘tomoegawara’ poles (巴瓦), ‘chigi’ (千木) and a combination of hanging fish at various points of the ridge known as ‘omogegyo’ (本懸魚), ‘kudarigegyo’ (降懸魚) and ‘hire’ (鰭), which are used as charms to prevent fire.

The main room in the centre is the largest of the three and is largely empty, save for the two tables that are placed in centre-rear of the room that lead to the door to the Main Hall.

During the Colonial Era, the doors to the Main Hall wouldn’t have been accessible by the general public as only Shinto Priests were permitted to approach the area where the gods are enshrined. Instead, the doors would have been closed and the table would have featured a large round mirror, known as a “shintai” (神体), which is considered the “looking glass” or a “repository” of the deities, making them accessible to humans.

In front of the tables, you’ll find a deep wooden box called an “saisen-bako” (賽錢箱), which is used for collecting “saisen” (賽錢), or monetary donations for the gods. The box has a series of wooden bars running across the top that allows people to drop in coins or paper bills, but makes its quite difficult to take anything out. While the box does look like its been around for a while, I haven’t seen anything that would indicate that its an original, so I’m guessing it was part of the restoration process that took place several decades ago.

From its original construction until just a few years ago, the interior of the building was lit simply by natural light. After the recent restoration however, electric lights have been added on the ceiling of the main shrine room to help illuminate the room. The lights that have been added are minimalistic and don’t really take away from the overall simplicity of the interior.

As the shrine has been converted into a Martyrs Shrine, you’ll find three placards (匾額) placed within the building that feature some beautiful Chinese calligraphy. Similar plaques with these phrases can be found at the other war memorial shrines around Taiwan, but the design of the ones used at the Taoyuan Shrine were made to blend in with the overall design of the building, making them a little less conspicuous.

The plaques are as follows:

“The Righteous Nation” (民族正氣)

“A Good Reputation for Eternity” (萬古流芳)

“Eternal Righteousness” (千秋正氣)

Note: In my most recent visit to the shrine, the placards had been removed but their hooks were still there. I’m unsure as to whether this was because they were in the process of being restored or if they’ve been removed for good. We’ll have to wait and see. The second placard mentioned above though is now located on the backside of the Middle Gate.

In both the east and west wings of the building you’ll find both of the rooms are filled with Spirit Tablets (神位), which were placed inside after the shrine was converted to the Martyr's Shrine. The plaques, which are set up in rows, commemorate and honour those who gave their lives in the lines of service for the Republic of China.

Keeping with Martyrs Shrine tradition, the western wing is known as the Literary Martyrs Shrine (文忠士祠) and is dedicated to the intellectuals who contributed to the revolution that helped the Chinese Nationalists topple the Qing Dynasty. The eastern wing is known as the Martial Martyrs Shrine (武忠士次) and is dedicated to those who died in the line of military duty.

I think it’s important to note that the fallen soldiers that are memorialized at the shrine today were Chinese and not Taiwanese - I don't say this to disrespect their their sacrifice, but few (if any) of them have anything to do with Taiwan. Ironically, if you wanted to actually pay respect to the Taiwanese who perished during the Second World War, you’d have to take a trip to the Yasukuni Shrine (靖國神社) in Tokyo, where they are honored as Martyrs.

Main Hall (本殿)

Finally, we’ve reached the Main Hall, otherwise known as the “honden” (本殿/ほんでん), the most sacred part of any Shinto Shrine, and the home of the gods.

Traditionally, the Main Hall is the area of a Shinto Shrine that is completely off-limits to the general public, and would have only been accessible to the priests who resided at the temple.

Today though, it is open to the general public.

If you are a fan of Shinto Shrines and have never seen one of these buildings up close, the Taoyuan Shinto Shrine is probably one of the only places in the world where you’re able to such a great view of a Main Hall in a shrine this size.

Although, it should go without saying that this probably violates a thousand or more years of Japanese tradition, the people in charge of the shrine are careful not to let people get too close, or climb the stairs to the former home of the gods.

On that note, as I’ve already mentioned in the first part of this blog, the Main Hall was formerly the home of several Japanese deities, but today is home to spirit tablets dedicated to a set of patriotic figures. The doors to the shrine are always open and you are free to take a look inside, but there is a gate and a sign that says that it is forbidden for anyone to actually walk up the small set of stairs. So bring a pair of glasses if you aren’t farsighted.

The Main Hall is constructed almost entirely of cypress using the ‘nagare-zukuri’ (流造) architectural style, one of the most widely used designs for these types of buildings, and is characterized by its asymmetrical gabled roof, known as a ‘kirizuma-yane’ (切妻屋根).

The non-gabled side of the roof is long and projects outwards with a steep flowing curve that covers the veranda and the steps of the shrine as well as meeting with the canopy (向拜) that leads to the hall from the Hall of Worship.

As is the case with most of the buildings constructed in the ‘hirari’ (平入) style, the entrance appears on the side with the longer section of roof, known as the ‘mae-nagare’ (前流) with the ‘ushiro-nagari’ (後流) on the backside being considerably shorter.

The roof is likewise covered with copper tiles, but the colour is the same shade of green that you’ve seen at the Administrative Building and the Purification Fountain and not the same colour as the Hall of Worship.

Similar to the Hall of Worship though, the roof features many of the same decorative designs on the gables.

There is something quite odd about the decorations on the roof though.

On the apex of the ridge, where the ‘onigawara’ should be located, you’ll find a fleur-de-lis, the stylized lily that is more common in France than it would be in Taiwan or Japan.

Under it, you’ll find three hearts, which is even stranger.

I spent a few hours trying to figure out where these came from to no avail.

My guess is that it was a result of the restoration project from the late 1980s and that they probably took some liberties with the design while also trying to remove Japanese elements from the shrine. After I noticed that though, I became aware that the same design was used on other parts of the shrine - on the Administrative building, Purification fountain, etc.

Why they actually chose that design is a mystery to me - but I hope to figure it out sometime.

Keeping with the traditional nagari design, the shrine is elevated off of the ground on a cement base, which helps to stabilize the building with the added assistance of a set of pillars that encircle the perimeter of the building.

The front of the shrine has a set of stairs that would have allowed the priests to open the doors to the shrine as well as a miniature ‘hisashi’-style veranda that wraps around the building on all four sides.

The veranda is supported by a network of smaller pillars that are connected directly to the cement base and the craftsmanship and carpentry on the veranda is exceptional.

One of the things you’ll want to take special note of are the beautifully constructed decorative railings that encircle the veranda of the building. Known as ‘kouran’ (高欄 / こうらん), appearing with three horizontal rails that curve at the ends and are expertly fitted within vertical posts or struts called ‘tsuka’ (束) without the use of nails.

Even though they may not seem particularly important, the stairs to the shrine, like mostly every other aspect of the shrine are also symbolic in nature. In total, there are thirteen steps to the main level, five of which are part of the concrete base while the others have been constructed using cypress.

The staircase, which is known as a half-step staircase (半步梯) has been strategically designed to only be wide enough for a single adult, but with the assistance of the canopy overhead, ensures that anyone who ascends the stairs does so with their head bowed.

This is intentional as a forced gesture of respect as you are climbing the stairs to approach the home of the deities, which you should be doing in the most humble way possible.

If you think about it, the Main Hall can be contextualized as a miniature version of the much larger shrine in front of it, but it is also the traditional home of the gods, which is why its architectural design is similar to what you would have seen in ancient Japan.

I highly recommend walking around the perimeter of the building to fully enjoy all of its beauty and to get a good look at all of its decorative elements. Remember that the ability to see one of these buildings so closely is a rare opportunity, so if you have the chance to see it, you should have a good idea of what you won’t be able to see when you visit shrines in Japan!

Getting There

Address: #200, Section 3, Chenggong Road, Taoyuan City (桃園市桃園區成功路三段200號)

The Taoyuan Shinto Shrine is located on Taoyuan’s Tiger Head Mountain (虎頭山), a short distance from the Taoyuan Train Station (桃園車站) and is easily accessible through public transportation.

If you’re driving a car or a scooter, the shrine has a small parking lot that is free of charge. If you’re visiting on the weekend however, the parking lot tends to be full most of the time, so you might have to park your car a bit further away and walk to the shrine.

To get to the shrine, simply input the address above into your GPS or Google Maps and you should have no problem.

One thing you’ll want to keep in mind is that the parking lot is located around the corner from the stairs on the Visiting Path. So, you’ll want to pass by the sign that says “Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine” and as you round the corner, you’ll take the first right turn.

If the parking lot is full, there are a couple paid parking lots nearby where you should be able to find parking.

Veterans Hospital Parking Lot (榮民醫院桃園分院停車場)

Veterans Hospital Weekend Parking Lot (榮民醫院假日收費停車場)

Dayou Mitsukoshi Department Store Parking Lot (新光三越桃園大有店)

The shrine is also easily accessible through public transportation, but even though there is a bus stop next to the shrine, the buses that you’ll end up taking will most likely end up dropping you off at the Taoyuan Veterans Hospital (桃園榮民醫院), which is a short walk from the shrine.

From Taoyuan Train Station

From Tonlin Department Store (統領百貨)

Taoyuan Bus (桃園客運): #105

From Huilong MRT Station (迴龍捷運站)

Taoyuan City Bus (桃園市區公車): #602

Youbike Accessibility

If you don’t feel like waiting for the bus and want to take a ride around Taoyuan, there are YouBike Stations at the front and back of Taoyuan Train Station, and if you want to drop off the bike, there are three stations near the shrine.

Link: Youbike Station Map

The Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine and Cultural Park is open seven days a week from 09:00-17:00 and entry is free of charge.

There are also guided tours that are provided free of charge between between 09:00-12:00 and 13:00 - 17:00 daily, but need to be booked in advance with a group of twenty or more.

As a national historic monument, the Taoyuan City government has done an excellent job preserving this piece of Taiwan's history and now that renovations are finally complete, visiting the shrine is even easier than ever with staff on site who can give guided tours and explain the history in greater detail to foreign guests.

Taoyuan may not be the most popular destination in Taiwan for tourists, but quite a few interesting destinations have popped up over the past few years and this is one of the ones that I think should be high on your list if you're rolling through town. The Tiger Head Mountain Park area itself has a number of locations within the park that are attractive tourist destinations themselves, and you could easily spend a day exploring the area.

If you are interested in the history of the Japanese Colonial Era, Taoyuan is an excellent place to visit as it is home to the Daxi Martial Arts Hall, Longtan Martial Arts Hall, Zhongli Police Dorms, Taoyuan Police Dorms, Daxi Police Dorms, etc.

An 80 year history may not seem as attractive to people as some of the centuries-old temples that you can find around the country but the fact that the shrine has been able to survive while so many others met their demise is remarkable. There are few places that you can visit in Taiwan that are like this shrine, so now that it is back in operation, I highly recommend a visit.

And before I leave, let me just throw you some shade..

Footnotes

118 Shinto Gods and Goddesses to Know About (Owlcation)

Encyclopedia of Shinto (Kokugakuin University)

Shinto Architecture (Wikiwand)

Colonial Constructs (Taiwan Today)

The Current Status and Development of Japanese Studies in Taiwan: from a Folklore-Centred Perspective (Taipei National University of Arts)

桃園忠烈祠暨神社文化園區 (Taoyuan Travel)

日人蓋桃園神社 兒孫80年後跨海來捐款 (UDN)

台灣日式建築的屋頂形式 (空間母語文化藝術基金會)

桃園神社-忠烈祠 (桃園市議會)

桃園忠烈祠暨神社文化園區簡介 (桃園市政府孔廟忠烈祠聯合管理所)

桃園忠烈祠 (Tony的自然人文旅記)

桃園神社導覽2:建築與思想 (上) (中) (下) (桃園歷史文化館區)

桃園神社 (美工阿宗趴趴走)

桃園神社 (Kevin Yu)

桃園市忠烈祠 (Wiki)