Here we go again.

This is my fourth go at posting about Taiwan’s Martyrs Shrines this year.

As I’ve already mentioned a few times over the past few months, when I was considering where I would focus as part of my yearly project for this blog, I came up with the idea to continue my work with regard to places of interest from the Japanese Colonial Era.

Albeit with a bit of a caveat.

I decided that I’d make a concerted effort to visit some of the various “Martyrs Shrines” around Taiwan, which were originally home to a Shinto Shrine.

It might be difficult to imagine, but Taiwan was once home to well-over two hundred Shinto Shrines.

However, as the Japanese colonial regime was replaced by the “Republic of China”, the majority of the them ended up being destroyed, with only a select few of the larger ones retaining a semblance of their former selves.

In my post about the National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine (台北忠烈祠) in Taipei, I listed fifteen of these former Shinto Shrines scattered throughout Taiwan (and on Penghu) that continue to exist in some form today.

Some of which I’ve already posted about:

National Revolutionary Martyrs Shrine (國民革命忠烈祠)

New Taipei City Martyrs Shrine (新北市忠烈祠)

Taoyuan Martyrs Shrine (桃園忠烈祠)

Tungxiao Martyrs Shrine (通宵忠烈祠)

Taichung Martyrs Shrine (台中忠烈祠)

Changhua Martyrs Shrine (彰化忠烈祠)

Yilan Martyrs Shrine (宜蘭忠烈祠)

Taitung Martyrs Shrine (台東縣忠烈祠)

That’s eight, so if your math is good, you’ll probably realize that I still have seven to go!

Even though 2020 has been a pretty terrible year with regard to travel, here in Taiwan we’ve been lucky that the government was proactive and on the ball, saving us from a massive outbreak of COVID-19.

But instead of taking trips overseas, many Taiwanese (and myself included) instead traveled around Taiwan to enjoy all that this beautiful country has to offer.

I took a several-week trip to the South East Coast to visit some places that have been on my list for a long as well as saving some time to hang out and relax on a beach. Two of the places on my list to visit were two of the Martyrs Shrines that I haven’t been to yet, namely the Taitung shrine and the Hualien shrine.

Suffice to say, one of the shrines ended up being extremely disappointing, while the other ended up being a really great experience. Today I’m going to introduce the latter of the two.

The Hualien Martyrs Shrine isn’t what you’d consider a popular tourist attraction by any means, but it is one of the prettiest of all the Martyrs Shrines in Taiwan, and was once home to an even more beautiful Shinto Shrine.

Let me start by introducing that shrine!

Hualien Shinto Shrine (花蓮港神社)

The “Hualien Shinto Shrine”, otherwise known as Karenko Shrine (花蓮港神社) or “Karenko jinja” was a Prefectural Level (縣社) shrine that existed on this site from 1915 until 1981, when it was demolished to make way for the current Chinese-style Martyrs Shrine.

The shrine was officially opened to the public on August 19th, 1915 (大正4年) and before becoming the central shrine in the prefecture, it was known simply as the “Hualien Harbour Shrine,” and just so happened to be one of the most architecturally significant shrines in Taiwan.

When I say architecturally significant, its not because the shrine was constructed in a way that differed from any of the other shrines around Taiwan or those back in Japan, but because at the time it opened, if you wanted to visit, you had to walk across a suspension bridge over the Meilun River (美崙溪).

Link: 花蓮市區內神社舊址導覽 (ARCGIS)

This would have made the traditional “Visiting Path” that you find at Shinto Shrines one of the longest in Taiwan and also would have provided some spectacular views of the shrine as you approached.

You’d likewise also would have had even better views of the city when you looked back from atop the hill.

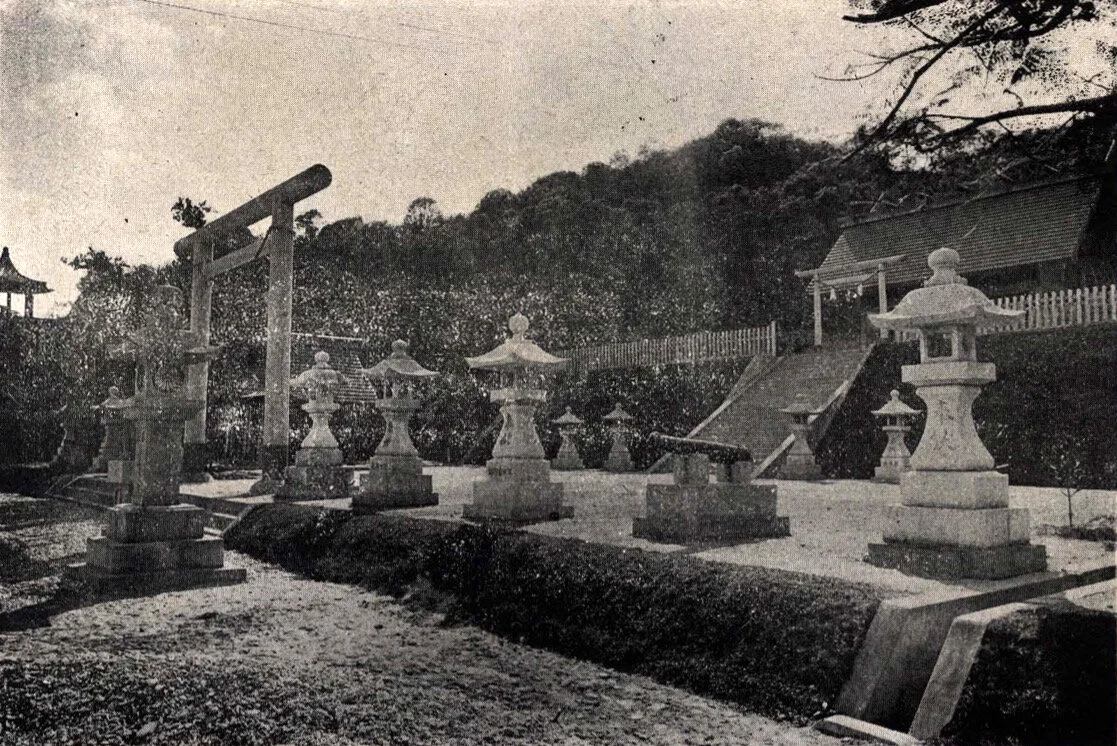

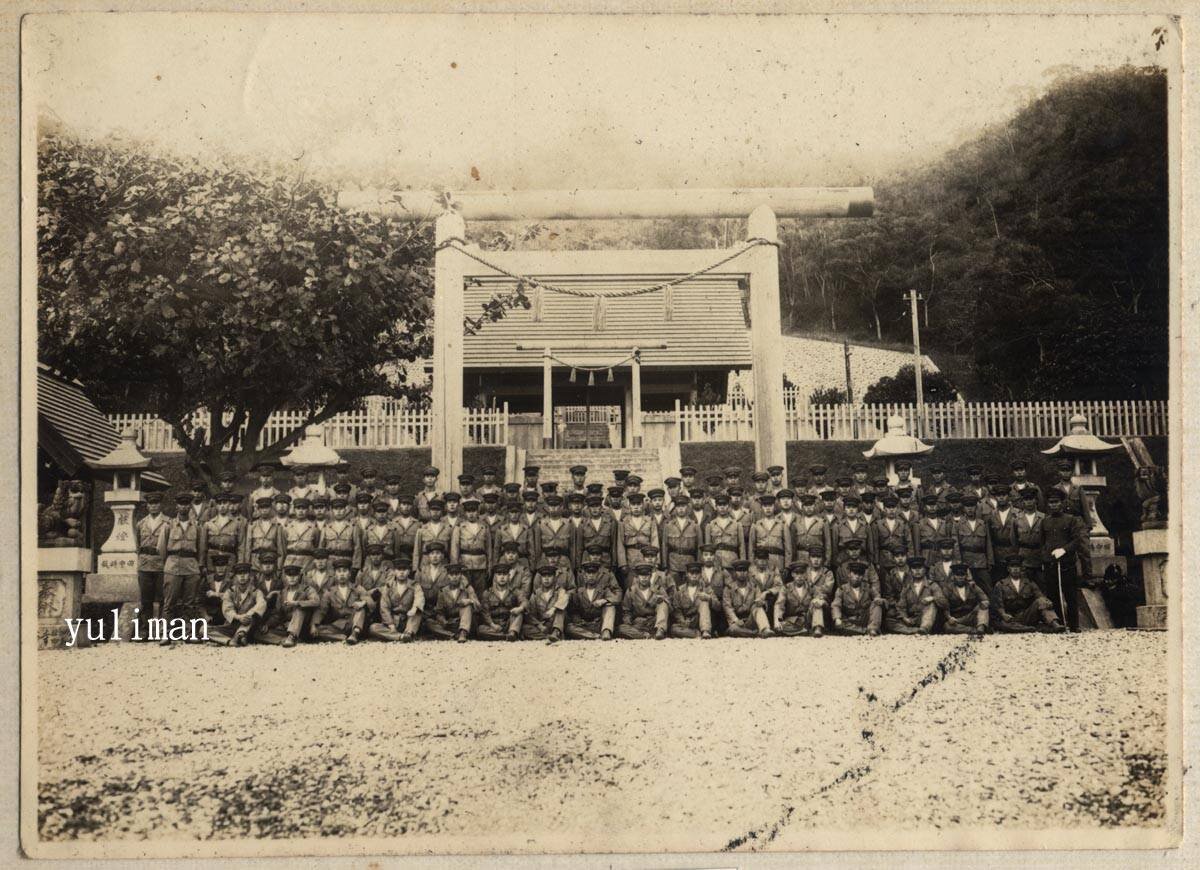

Fortunately the shrine was so beautiful that there are a multitude of historic photos from various sources around Taiwan that I’m able to share with you today.

As always though, the former Shinto Shrine consisted of the following:

Two large Shrine Gates or “Torii” (鳥居)

A walking path or “Sando” with a suspension bridge (參道)

Stone Lanterns or “tōrō” (石燈籠) on either side of the walking path.

Stone Guardian Lion-Dogs or “Komainu” (狛犬)

An Administration Office or “Shamusho” (社務所)

A Purification Fountain or “Chozuya” (手水舍)

A Hall of Worship or “Haiden” (拜殿)

A Main Hall or “Honden” (本殿).

As the largest shrine in Hualien, the shrine was officially designated a Ken-sha (縣社) or “Prefectural Level” shrine a few short years after it opened on March 2nd, 1921 (大正10年).

As a Prefectural Level shrine, the ‘kami’ (deities) enshrined within were quite important, but as was the case with almost every other large shrine of its kind in Taiwan, the deities were actually all familiar figures, which included the Three Deities of Cultivation (開拓三神) and Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王.)

The ‘Three Deities of Cultivation’ (かいたくさんじん / 開拓三神), consist of three figures known for their skills with regard to nation-building, farming, business and medicine.

The three “Kaitaku Sannin” are as follows:

Ōkunitama no Mikoto (大國魂大神 / おおくにたまのかみ)

Ōkuninushi no Mikoto (大名牟遲大神 / おおなむちのかみ)

Sukunabikona no Mikoto (少彥名大神 / すくなひこなのかみ)

The first mention of these deities was in the ‘Birth of the Gods’ (神生み) section of Japan’s all-important ‘Kojiki’ (古事記), or “Records of Ancient Matters”, a thirteen-century old chronicle of myths, legends and early accounts of Japanese history, which were later appropriated into Shintoism.

While these deities are also quite common among Japan’s Shinto Shrines, they were especially important in Taiwan due to what they represented, which included aspects of nation-building, agriculture, medicine and the weather.

Given Taiwan’s position as a new addition to the Japanese empire, ‘nation-building’ and the association of a Japanese-style way of life was something that was being pushed on the local people in more ways than one.

Likewise, since the economy in Taiwan at the time was primarily agricultural-based, it was important that the gods enshrined reflected that aspect of life.

Coincidentally, even though the colonial era ended almost eight decades ago, this is something that remains somewhat of a constant as you’ll find that one of the most important deities in Taiwan is the Chinese folk religion “Earth God” (土地公/福德正神), who has a court that performs similar roles as the three mentioned above.

Interestingly, even though the origins of the Three Deities of Cultivation dates back well-over a thousand years, the other ‘kami’ enshrined here was a much younger one. In fact, most of the larger Shinto Shrines constructed in Taiwan during the colonial era were home to shrines dedicated to this specific deity who was known in life as “Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa.”

Prince Yoshihisa, a major-general in the Japanese imperial army, was commissioned to participate in the invasion of Taiwan. Unfortunately for the Prince, he contracted malaria and died just outside of Taiwan making him the first member of the Japanese royal family to pass away while outside of Japan in more than nine hundred years.

Shortly after his death he was elevated to the status of a kami under state Shinto and was given the name “Kitashirakawa no Miya Yoshihisa-shinno no Mikoto“, becoming one of the most prevalent deities here in Taiwan as well as being enshrined at the Yasukuni Shrine (靖國神社) in Tokyo.

Link: Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (Wiki)

As I mentioned above, when Taiwan’s Japanese Colonial Era came to an end in 1945, most of Taiwan’s smaller Shinto Shrines were torn down by the incoming regime, while the larger prefectural shrines were (for the most part) converted into Martyrs Shrines.

The Hualien Shinto Shrine was surprisingly one of the few major Japanese-era shrines in the country to actually retain much of its original design for decades after the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan.

In 1950 though it was converted into the Hualien Martyrs Shrine (花蓮縣忠烈祠), with only minor changes taking place to the buildings on-site.

In 1970 (民國59年), the suspension bridge, aptly named “The Shrine Bridge” (宮の橋) was destroyed by a typhoon and as Hualien had grown exponentially, the local authorities decided it was time to replace the pedestrian bridge with a much larger cement one which would allow more than just foot traffic to cross the river.

Then, in 1972 (民國61年), the government of Japan signed a Joint Communiqué with the People’s Republic of China, starting formal diplomatic relations between the two countries.

One of the prerequisites for the agreement was that the Japanese government follow suit with America and the United Nations and drop relations with the Taipei-based government of the Republic of China.

The Japanese government’s decision to drop formal relations with Taiwan at that time was considered a major slap in the face to the people of Taiwan, which had up until then very favorable relations with their former colonial rulers.

Not only did this create quite a bit of anti-Japanese sentiment around Taiwan, but it also spurned the government into action with a retaliatory policy of tearing down anything related to Japanese culture or whatever remained from the Japanese colonial era.

Link: Japan-Taiwan Relations (Wiki)

One of the victims of that anti-Japanese sentiment turned out to be this shrine, which was demolished and converted into a grand Northern-Chinese Palace style shrine, reopening to the public in 1981.

Even though the Hualien Shinto Shrine outlasted many of its contemporaries in Taiwan, it still ultimately suffered the same fate and when it was demolished, not much was left of the original shrine.

Today, one of the only pieces of the shrine that remains is the traditional “Shinme” (神馬/しんめ) or “Sacred Horse”, which is still standing near the shrine.

The “Kikumon” (菊紋) or the “Chrysanthemum Seal” of the Japanese Royal Family which typically adorns the belly of the horse however has been painted over with the star of the Republic of China.

Hualien Martyrs Shrine (花蓮忠烈祠)

As mentioned above, the Hualien Martyrs Shrine that exists today only dates back to 1981 (民國70年), making it a relatively young one by Taiwanese temple standards.

Having been around for the last four decades, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the shrine is even newer as it appears to be in pristine condition, thanks to the constant attention it receives from the local government.

The shrine was constructed in the Northern-Chinese Palace Style (中國宮殿式建築), making its architectural style similar to many of the other Martyrs Shrines in Taiwan in that its design closely mimics that of the Forbidden Palace in the Chinese capital of Beijing.

Even though the shrine is open daily, it’s not likely that the actual shrine rooms will be open to the public as they are generally only open on special occasions.

This shouldn’t be a huge surprise though - Martyrs Shrines aren’t really the typical kind of Taiwanese temple where people show up at regular intervals to show their respect and make a wish. They tend to be much more ceremonial in nature and are mostly used for propaganda purposes.

So if you show up hoping to see inside the shrine room, you’re probably going to be disappointed.

Nevertheless, in addition to honouring the war dead of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces, this shrine is also home to Spirit Tablets (牌位) for Koxinga (鄭成功) as well as Liu Yongfu (劉永福) and Qiu Fengjia (邱逢甲).

Liu was the commander of the celebrated Black Flag Army (黑旗軍), who later in life became the President of the short-lived Republic of Formosa (臺灣民主國). Qiu on the other hand was a Hakka poet, a renowned patriot, and the namesake for Taichung’s prestigious Fengjia University (逢甲大學).

Despite the obvious disparity between the current Chinese-style design and the former Japanese-style design of the buildings, the landscape still maintains much of its original design, so as I introduce each of the different parts of the current shrine, I’ll do so in a way that looks at the shrine through the lens of the former Shinto Shrine to contrast and compare the older and current versions of the shrine.

The Visiting Path (參道)

The Visiting Path, once one of the defining features of the Shinto Shrine has undergone significant changes since the shrine was converted into a Martyrs Shrine.

First, it goes without saying (as I already mentioned above) that the original pedestrian bridge over the Meilun River has been replaced with a much larger bridge.

Today the path to the shrine is simply a set of cement stairs that bring you up to the main gate.

The left and right side of the stairs used to be adorned with cascading platforms of stone lanterns, but today they have all been removed, which has allowed for the staircase to be significantly widened.

The Shrine Gate (鳥居)

Upon reaching the top of the stairs, you’re be met with a beautiful red and white multi-tiered Chinese-style Pailou Gate (牌樓), which has a plaque in the middle that reads “Martyrs Shrine” (忠烈祠) in golden Chinese characters.

This gate is a relatively newer addition to the shrine as the original gate that was constructed in 1981 was destroyed thanks to a magnitude seven earthquake, which I’ll talk about more later.

However, even though the current shrine gate is quite new, it is still beautifully designed and is probably one of the first things you’ll notice about the shrine as you approach from ground level.

The Hall of Worship (拜殿)

The area where the Shinto Shrine’s Hall of Worship, or “Haiden” (拜殿) once existed has been replaced by another kind of ‘gate’, which you have to pass through to reach the main area of the shrine.

This “gate”, which is officially known as the “Hall of Righteousness” (正氣殿) is elevated another level above where the Shrine Gate stands, so you’ll have to walk up another set of stairs to reach it.

Before walking up the stairs though, you’ll likely notice the characters “英烈千秋” split into two on either side of its stairs. The phrase is loosely translated as “Eternal Heroes”, which is obviously a nod to the Martyrs enshrined within.

As you walk through the gate you’ll notice on one side that there is a door to an Administrative Office, which looks like it hasn’t been opened in a while. When you walk through the gate, you’re met with some more beautiful red pillars that lead to another set of stairs bringing you to the final level where the Main Halls are located.

Interestingly, when the Shinto Shrine was first converted into the Martyrs Shrine, the “Haiden” was renamed “Hall of Righteousness” and retained its original design up until being torn down in the 1980s.

Today, the Chinese-style version retains the same name, which is a reflection of the history of this shrine.

The Main Hall (本殿)

As is tradition with larger Shinto Shrines, the Main Hall, “Honden” area would have been off-limits to the general public. Today though the area where the hall once stood has been significantly altered to allow for three large Chinese-style buildings.

The Main Hall or the “Martyrs Shrine” (主殿)

The Left Hall or “The Hall of Benevolent Admiration” (仰仁殿)

The Right Hall or “The Hall of Sublime Virtue” (崇德殿)

While the Main Hall is the area where you’d go to worship the Martyrs of the Republic of China’s Armed Forces who were killed in the line of duty, I’m assuming that the other two halls (which have different names) follow tradition and are Civilian Wings (文武忠烈祠), venerating the figures mentioned above as well as local heroes who died doing something “righteous.”

If that is the case, the Literary Martyrs Shrine (文忠士祠) would be dedicated to the intellectuals who contributed to the ‘revolution’ that helped the Chinese Nationalists topple the Qing Dynasty, and is likely home to the Spirit Tablet for Liu Fengjia.

Meanwhile the Martial Martyrs Shrine (武忠士次) would be dedicated to those martyrs who died during the early stages of the revolution and would include Koxinga and Liu Yongfu.

Unfortunately this is all just speculation as there is very little information about the shrine available, even in Chinese - and because you can’t actually even enter the shrine room to see.

Interestingly, while I was working on the photos for this post, I noticed something odd about the shrine.

It seemed no matter what I did, some of the photos weren’t straight. I was lining up the horizon with all the straight lines in photoshop and kept failing until I realized that none of it was my fault.

The shrine was actually sinking and tilted heavily to the right.

I did some checking and discovered that in 2005, Typhoon Longwang (龍王颱風) caused significant damage to the shrine with a subsequent magnitude seven earthquake adding to the woes of the already weak foundation.

Link: 花蓮忠烈祠修繕完工 即將開放參觀 (中時新聞網)

Still, even though the shrine is a bit slanted, it is a really nice place to visit and the colours of this palace-style shrine are really great for photos.

Getting There

Address: #82 Fuxing New Village, Hualien City (花蓮縣花蓮市970復興新村82)

The Hualien Martyrs Shrine is located near the busy downtown area of Hualien and is easily walkable from wherever you are coming from.

That being said, Hualien is a pretty big space, so some people might not really be in a hurry to go on a walking tour of the city.

Unfortunately, the English address I’ve translated above isn’t really going to offer you much help getting to the shrine. If you copy the Chinese though, you should have no problem.

The reason for this is because the address for the shrine is a little strange and it probably gives Google Maps a bit of a headache.

The shrine is essentially located at the end of Linsen Road (林森路), where you’ll have to cross a bridge to get to the Meilunshan Park (美崙山公園).

Unfortunately, when it comes to public transportation, you’re somewhat out of luck.

There are city buses in Hualien, but none of them really bring you all that close to the shrine, and the route that travels the closest has recently terminated its service, so if you don’t have a car or scooter for your trip, you’re probably going to have to walk or take a cab to get to the shrine.

I could list a number of buses that get you within a ten to twenty minute walk from the shrine, but if you’re already in the downtown area, its probably better to just walk.

Of all the Martyrs Shrines I’ve visited thus far, the Hualien shrine is probably one of the prettiest. It probably goes without saying though that this is also thanks to the Shinto Shrine which once stood in its place.

From the outset, I didn’t expect that the final version of this article would turn out to be the most detailed resource available (in any language) about the shrine, but it was certainly frustrating to write as there is very little information available.

Nevertheless, it goes without saying that there are countless things to see and do while visiting Hualien, so even though this shrine isn’t probably very high on most people’s list of places to visit, I’d still recommend stopping by to check it out if you’re in the area.

It won’t take you too much time and if the weather is nice, the shrine absolutely shines.