At some point during my elementary school years, my grandma arrived at our house to collect my sister and I for a trip to visit the extended family. Every summer we’d have a several day long family reunion in Halifax, but this time was different. Most of the time my grandfather would be in charge of driving us on the two hour journey to this city, but this time, he was busy with work, so he couldn’t join us. Instead, we drove to a local train station, and for the first time in my life, I stepped foot on a train.

For people here in Taiwan, getting on a train for the first time probably isn’t one of those memorable experiences that they remember vividly later in life, it’s just something that is simply part of daily life for a lot of people here that they take it for granted. For Canadians, though, taking a train, sadly, tends to be a very rare occurrence. I remember getting off the train, walking down a large covered platform, and then emerging into a massive open building, probably one of the largest buildings I had been in by that point in my life, and was in awe of the beauty of the European-style building.

Decades later, I found myself on a train bound south to the central Taiwanese city of Taichung for a weekend trip. When we arrived, I remember getting off of the train, walking down the platform to the station hall from which we’d start our weekend of exploration. Putting my ticket into the turnstile, I walked into the massive station, and was almost automatically transported back to that vivid childhood memory of my first experience on a train.

The station was busy, but the interior was massive, with high ceilings, white walls and European-style architecture. It wasn’t an experience that I was expecting, but it was one that I thoroughly enjoyed.

I didn’t particularly know that much about Taiwan at the time, so I never really put much thought into why the building appeared the way it did. but I enjoyed the quick reminder of my childhood experience, and then walked out of the station to check into our hotel for the weekend. Now that I’ve been in Taiwan for quite a while, and I’ve learned a lot about the nation’s history, I’m a little sad that I didn’t spend time taking photos of the station as it was while it was still in action.

Sadly, the historic Taichung Station, which had served the community just short of a century, like many other historic train stations around the country, was replaced with a modern-looking monstrosity, but came with the promise of increased efficiency, and for some people, that’s more important.

Actually, the modern station is quite beautiful in its own right, I shouldn’t be so harsh in my description. It’s a very well-designed open space, but it’ll never be as iconic as its predecessor.

Of the major Japanese-era railway stations, Taichung’s beautiful railway station was part of a short list of buildings that remained in operation almost a century after they were constructed. Today, only Hsinchu Station (新竹車站), Chiayi Station (嘉義車站) and Tainan Station (臺南車站) remain, and unsurprisingly, it seems like they might be running short on time, as well. Fortunately, unlike the disappearance of Japanese-era railway stations in Keelung (基隆車站), and Hualian (花蓮車站), local authorities had the foresight to preserve the historic station, giving the people of Taichung the peace of mind that even though some things might change, others would stay very much the same.

Today, I’m going to introduce the historic Taichung Train Station, it’s history, and its architectural design. Even though the station has recently been decommissioned, it has become part of a large cultural park that focuses on the history of the railway, something for which you’ll discover Taichung owes much of its prosperity to, so if you find yourself visiting the city today, a visit to the Railway Cultural Park that they have set up is a pretty good way to spend some of your time.

Taichung Railway Station (臺中驛 / たいちゆうえき)

To introduce the historic Taichung Railway Station, I’m going to do a bit of a deep dive into the events that led up to the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan, and the development of the railway, which ushered in an era of modernity and economic opportunity that the people of Taiwan had yet to experience. While explaining how the railway became an instrumental tool for fueling the Japanese empire’s goal of extracting the island’s precious natural resources, I hope to also offer a bit of context as to why this station in particular became so important. Before I start, though, I need to reiterate that the building I’ll be introducing isn’t the current railway station, it’s the historic building that is located directly next door.

For anyone who has grown up in the Taichung, terms like ‘First Generation’, ‘Second Generation’ or ‘Third Generation’ don’t really mean anything - there’s only one Taichung Station, and there’s that newer-looking building next door where the trains currently come and go from. Understandably, when you’ve been the beating heart of a city for well over a century, it takes people a while to adjust to the newer situation.

The history of the railway in Taiwan dates back as early as 1891 (光緒17年), just a few short years prior to the arrival of the Japanese. A first for Taiwan, the railway project is arguably one of the most ambitious development projects undertaken by the Qing government while they still held control of the island. Under the leadership of Liu Mingchuan (劉銘傳), who would end up being the last governor of Taiwan, at its height, the Qing-era railway stretched from the port city of Keelung (基隆) to Hsinchu (新竹). However, even though the project was led by foreign engineers, the end result turned out to be a rudimentary, treacherous route that ultimately came at far too high of a cost to continue financing. Suffice to say, none of this should be particularly surprising, especially when you take into consideration that during the two centuries that the Qing controlled portions of the island, they never particularly cared very much about developing it, and this was especially true during the final few decades of their administration as they were more occupied with war (and revolution) at home.

The Manchu’s came to power in China at a time when the previous rulers had become far too weak to contend with constant rebellions and civil disorder. In what may seem like a case of history repeating itself, by the late 1800s, Qing rule had similarly become incompetent, and corruption was rife throughout the country. Putting it bluntly, the level of corruption and incompetence prevented China from modernizing its military, but it also resulted in them shooting themselves in the proverbial foot with some diplomatic missteps that led to war with Japan.

Known today as the ‘First Sino-Japanese War’ (1894-1895), the whole affair ended about as quickly as it began, resulting in considerable embarrassment for the Qing rulers, who were completely unprepared to wage a modern war against a well-equipped Japanese military. The year-long war ultimately shifted the balance of power in Asia from China to Japan, and would be one of the catalysts for revolution in China that would just a few years later bring thousands of years of imperial rule to an end.

Unable to successfully wage war against the Japanese, the Qing were forced to sue for peace a little more than six months into the war. This resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki (下関条約), which forced China to recognize the independence of Korea, and the Chinese would have to pay Japan reparations amounting to 8,000,000kg of silver. More importantly with regard to this article however, it also meant that Taiwan, and the Penghu Islands would be ceded to Japan in perpetuity.

Shortly thereafter, the Japanese set sail for Taiwan, landing in Keelung on May 29th, 1895. Upon arrival, Japanese forces were met with fierce resistance from the remnants of the Qing forces stationed on the island, local Hakka militias, and the indigenous people. Over the next five months, the Japanese gradually made their way south fighting a nasty guerrilla war that ‘officially’ came to an end with the fall of Tainan in October. That being said, even though the military had more or less taken control of Taiwan’s major towns, the insurgency and resistance to their rule lasted for quite a few more years, resulting in some brutal events taking place during that time.

Nevertheless, similar to the war with China, the superiority of the modern Japanese military easily dispatched the local armies, which vastly outnumbered them. The campaign, however taught the Japanese a hard, yet valuable lesson as figures show that over ninety-percent of the Japanese military deaths were caused by malaria-related complications.

Taiwan’s hostile environment turned out to be one of the main reasons why the Qing were so ambivalent towards the island, but is something that the Japanese were intent on addressing, especially since they were invested in extracting the island’s vast treasure trove of natural resources. To accomplish that mission, they would first have to put in place the necessary infrastructure for combating these diseases.

One of the colonial government’s first major development projects got its start shortly after the first Japanese boots stepped foot in Keelung in 1895. The military had brought with them a group of western-educated military engineers, and they were tasked with getting the existing Qing-era railway back up and running, as well as coming up with proposals for extending the railway around the island. As the military made its way south, the team of engineers followed close behind surveying the land for the future railway. By 1902, the team came up with a proposal for the ‘Jukan Tetsudo Project’ (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), otherwise known as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project,’ which would have a railroad pass through each of Taiwan’s established western coast settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄).

Construction of the railway was divided into three phases with teams of engineers spread out between the ‘northern’, ‘central’ and ‘southern' regions of the island. Amazingly, in just four short years, from 1900 and 1904, the northern and southern portions of the railway were completed, but due to some unforeseen complications, the central area met with delays and construction issues due to the necessity for the construction of a number of bridges and tunnels through the mountains.

Nevertheless, the more than four-hundred kilometer western railway was completed in 1908 (明治41), taking just under a decade to complete, a feat in its own right, given all of the obstacles that had to be overcome. To celebrate this massive accomplishment, the Colonial Government held an inauguration ceremony within the newly established Taichung Park (台中公園) with Prince Kanin Kotohito (閑院宮載仁親王) invited to take part in the ceremony.

The Japanese authorities touted the completion of the railway as part of a new era of peace and stability in Taiwan, and one that would help to usher in a new period of modernization, one that would bring economic stability to the people of the island - and for the most part, they were right about that.

The completion of the railway was instrumental in the development of the island and was a stark contrast from what the Qing considered a “ball of mud beyond the pale of civilization” (海外泥丸,不足為中國加廣) to an integral part of the Japanese empire.

Link: Mid-Lake Pavilion (湖心亭)

While the construction of the railroad, for the most part, seems to have gone by quite smoothly, as mentioned earlier, the central region was faced with delays in its completion in part due to poor planning and the necessity for the construction of large bridges and tunnels, which took longer than anticipated. That being said, by 1905, there were trains running a limited service route within Taichu Prefecture (臺中廳 / たいちゅうちょう) prior to their eventual connection with the northern and southern portions of the railway across the Da’an (大安溪) and Dadu (大肚溪) rivers.

One of the stations along the limited service route was the First Generation Taichung Railway Station (台中停車場), a modest single-story wooden station hall, which officially opened on June 10th, 1905 ( (明治38年). For the three years prior to the completion of the railway, the ‘Taichung Line’ connected the downtown of Taichung with Koroton Station (葫產激驛 / ころとんえき), Tanshiken Station (潭仔乾驛 / たんしけん), Ujitsu Station (烏日驛 / うじつえき), and Daito Station (大肚驛 / だいとえき), known today as Fengyuan (豐原), Tanzi (潭子), Wuri (烏日) and Chenggong (成功) Stations, respectively.

With the completion of the Western Trunk Railway in 1908, Taichung, like many other major settlements around Taiwan experienced an economic boom, and as its economy thrived, more and more people made their way to the city to take part in the economic successes, that were in large part thanks to the railway. As the most important passenger and freight station in central Taiwan, Taichung Station quickly became an extremely busy place, and after less than a decade, the city had already outgrown its small wooden station hall. Thus, when the decision was made to replace the original station with a new one. This time, though, Taichung Station would become one of the largest stations on the island and would be one that reflected the prosperous community that it served.

That being said, while construction of the new station was getting underway, some of the issues and delays caused during the construction of central Taiwan’s railway ended up persisting long after its completion. With the constant threat of earthquakes and typhoons creating major service disruptions, and the fact that central Taiwan was an important region for the extraction of sugarcane, fruit, and other commodities, the Railway Department of the Governor General of Taiwan (台灣總督府交通局鐵道部) was forced to come up with a solution to the problem. The answer came in the form of the “Kaigan-sen” (かいがんせん / 海岸線), or the Coastal Railway Branch Line, which started just south of Hsinchu and connected with the Western Trunk railway in the south of Taichung.

Link: The Coastal Railway Five Treasures (海線五寶) | Tai’an Railway Station (泰安舊車站)

The ‘Second Generation Taichung Railway Station’ officially opened on November 6th, 1917 (大正6年) - Much larger than the first generation building, the 436㎡ (132坪) station was constructed with reinforced concrete, red bricks and a beautiful wooden roof using a mixture of European Renaissance Architectural design. The construction of the second generation station was also an important time with regard to the expansion of the platform space, which was expanded to a size of 403㎡ (122坪), offering a covered roof for people waiting for their trains to arrive, and the installation of an underground walkway to replace the overpass that was constructed for the first generation building.

Over the following century, Taichung Station became one of the longest-serving symbols of the city, sharing important cultural and historic links with the people of Taichung. The station has lived through war, the subsequent authoritarian era, and has witnessed first hand a modern city develop around it. Like many of its contemporaries, however, the station fell victim to modernity, and in 2016, ninety-nine years after the first train rolled into the station, the final train departed.

It may have been the end of an era for the storied station hall, but we are fortunate that the local government had the foresight to realize that the historic building holds a special place in the hearts of the citizens of the city, said to ‘served as the iconic beating heart of the city.’ If they tore it down and replaced like so many of the other historic railway stations around the country, there might have been riots in the streets. Today, the historic Taichung Railway Station is part of a large railway cultural park next to the current station, and the people of Taichung, and the rest of us, are able to enjoy its continued existence.

Before I move on to detailing the architectural design of the station, I’ve put together a timeline of events in the dropdown box below with regard to the station’s history for anyone who is interested:

-

1896 (明治29年) - The Colonial Government puts a team of engineers in place to plan for a railway network on the newly acquired island.

1902 (明治35年) - After years of planning and surveying, the government formally approves the Jukan Tetsudo Project (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), a railway plan to be constructed along the western and eastern coasts of the island.

1905 (明治38年) - The First Generation Taichung Station (台中停車場) opens for operation.

1908 (明治41年) - The 400 kilometer Taiwan Western Line (西部幹線) is completed with a ceremony held within Taichung Park (台中公園) on October 24th. For the first time, the major settlements along the western coast of the island are connected by rail from Kirin (Keelung 基隆) to Takao (Kaohsiung 高雄).

1909 (明治42年) - A cross-platform sky bridge is constructed alongside the first freight warehouse.

1913 (大正3年) - The Western Trunk Railway is extended further south to Pingtung (屏東), known then as Ako (阿緱/あこう).

1917 (大正6年) - Construction on the Second Generation Taichung Railway Station is completed with an official opening ceremony held on November 6th.

1919 (大正8年) - Construction on the "Kaigan-sen” (かいがんせん / 海岸線), coastal branch railway in the Miaoli-Taichung area gets underway.

1922 (大正11年) - The Coastal Railway is completed and opens for operation.

1923 (大正12年) - Crown Prince Hirohito makes an official visit to the city.

1925 (大正14年) - Prince Chichibu (秩父宮雍仁親王) makes an official visit to the city.

1926 (昭和1年) - Prince Takamatsu (高松宮宣仁親王) makes an official visit to the city.

1935 (昭和35年) - The magnitude 7.1 Shinchiku-Taichū earthquake (新竹‧台中地震 / しんちく‧たいちゅうじしん) with an epicenter in nearby Houli (后里) rocks the island becoming the deadliest quake in Taiwan’s recorded history and causes massive damage around the island.

1945 (昭和45年) - The station is heavily damaged during Allied Bombing raids.

1946 (民國35年) - President Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣介石) marks his first visit to Taichung, traveling by train.

1947 (民國36年) - Residents of Taichung hold a ‘228 Incident’ (二二八事件民眾起意大會) speaking event outside of the railway station, resulting in one of the first government crackdowns in central Taiwan.

1949 (民國38年) - The Rear Station Hall (後站) officially opens.

1964 (民國53年) - The Rear Station Hall is restored and renovated.

1979 (民國68年) - The Taiwan Railway Corporation completes construction on the electrification of the Western Trunk Line.

1995 (民國83年) - The government designates Taichung Station as a Second Grade Protected Historic Building (二級古蹟).

1999 (民國88年) - The devastating 921 Earthquake (921大地震) in central Taiwan causes a tremendous amount of damage to the railway, shutting it down for almost two weeks.

2005 (民國94年) - Taichung Railway Station celebrates its centennial, and the earthquake reparation work on the station is completed after a several year long project.

2012 (民國101年) - Construction on the Third Generation Elevated Taichung Station (臺中車站高架化新站) breaks ground.

2016 (民國105年) - On October 15th, the final express train to pass through the historic ground-level railway station is dispatched from Pingtung on its way to Taipei. The next day, the first northbound train departed from the elevated station at 6:25am, and a few minutes later, the first southbound train departed at 6:33am.

2017 (民國106年) - The Second Generation Taichung Railway Station officially celebrates its centennial anniversary.

2020 (民國109年) - The massive 19,800m2 Taichung Railway Cultural Park (臺中驛鐵道文化園區) is officially inaugurated, and the historic railway station is reopened to the public as part of a park that will continue to expand over the next few years as other historic buildings are restored.

Architectural Design

Looking back, it’s safe to say that the construction of Taiwan’s major railway stations certainly wasn’t an undertaking that the Japanese authorities took lightly. For each of Taiwan’s major population centers, the colonial government constructed a building that was ostentatious not only in its size, but it’s architectural design as well. For those of you who live in or have visited Taiwan, you may find it difficult to believe, but over a century ago, the island was pretty much devoid of development - prior to the arrival of the Japanese in 1895, it would have been extremely rare to see major construction projects like this, so massive buildings like this would have been something completely new to the people living here.

To put it in perspective, the construction of this station is likely to have aroused a similar type of awe and amazement as Taipei 101 did while it was under construction.

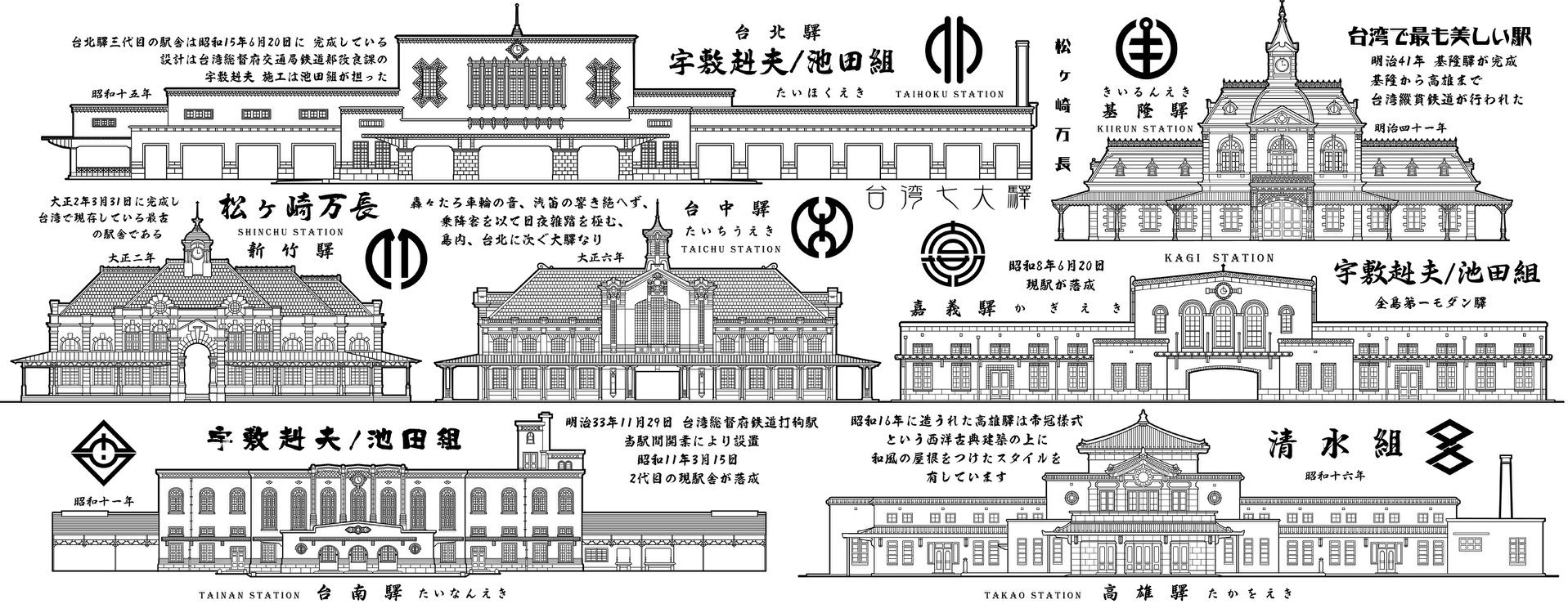

Of particular note, the railway stations constructed in Keelung, Taipei, Hsinchu, Taichung, Chiayi, Tainan, and Kaohsiung were highly regarded for their architectural beauty, most of which made use of a fusion of European and Japanese architectural design, with reinforced concrete, something that was quite uncommon, and very expensive, in the early years of the colonial era.

Something I’ve found to be quite a head-scratcher, and what seems to be one of the most common inaccuracies that you’ll find with regard to discussions about the Taichung Railway Station is the ‘person’ credited with its architectural design. So, let me take a minute to explain what’s actually getting lost in translation here. Most of the resources you’ll find regarding the architectural design of the station is that it was designed by an architect named Tatsuno Kingo (辰野 金吾 / たつの きんご), and oddly enough, both the Chinese and English resources that you’ll find misinterpret this fact.

In actuality, Tatsuno is fondly remembered as one of the founding members of the Architectural Institute of Japan, first studying under Josiah Conder, who is considered the “father of Japanese modern architecture,” before traveling to study architecture at the University of London. When he eventually returned to Japan, he took up a position as the Dean of Architecture at the University of Tokyo, and instructed many of the young designers who would follow in his footsteps. Tatsuno’s designs were inspired by the work of Christopher Wren and William Burges, architects whose work he studied during his years at the University of London. As part of the first generation of European-trained Japanese architects, Tatsuno’s architectural styles influenced many of those who followed in his footsteps designing modern buildings in the European Classical and Victorian styles.

In the early days of Taiwan’s colonial era, young Japanese architects likely salivated at the opportunity to come to Taiwan. The island was essentially a blank canvas, and with the government’s support, they hopped on boats and came to a place where they had considerably more freedom to be creative with their urban development projects. That being said, Tatsuno, who is known for his work with the Bank of Japan, Tokyo Station, the National Sumo Arena, etc, never actually made it to Taiwan, passing away in 1919.

Nevertheless, in order to do the building honor, the architects at the Department of Public Works (臺灣總督府交通局鐵道部) took inspiration from Tatsuno’s work, which by that time had become known as the “Tatsuno style” (辰野式), and with so many of his students employed in Taiwan, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that buildings like Presidential Building (總統府), the Monopoly Bureau (專賣局), Taichung City Hall (臺中市役所), and the Ximen Red House (西門紅樓), among others, were all inspired by his work.

Making use of a combination of red bricks and white stone in decorative patterns, with the addition of dormer windows, straight-flowing lines and beautiful stone pillars, Tatsuno’s style imitated the architectural designs he observed while studying in London. Combining elements of Gothic, Baroque, Renaissance and Art-Nouveau in a mixture that architects of the era referred to as “Free Classical,” (自由古典風格) it’s rather obvious that quite a few of these elements are elegantly put on display within the Taichung Railway’s architectural design. So, even though Tatsuno didn’t personally design the station, a quick look at one of his masterpieces, Tokyo Station (東京驛) should give you a pretty good idea as to where the inspiration for this station came from.

Interestingly, Tatsuno Kingo (金吾) was often referred to instead as “Kengo” (堅固), a play on words in Japanese that referred to the firmness and symmetry for which his buildings were designed. With that in mind, following the Tatsuno-style of ‘Free Classical’ design, the Taichung Train Station follows suit with equally-sized eastern and western wings connected to a tower located directly in the center of the building.

While the building looks large enough to have several floors, once you enter, you’ll notice that the interior space features high ceilings, which are naturally lit by the large windows in the center and along the eastern and western wings. The lobby is a bright and spacious room featuring white walls with the wings only separated only by stone columns, which help to stabilize the weight of the roof above.

If you look carefully at the stone columns within the building, you’ll notice a bit of localization going on with the inclusion of decorative elements featuring a variety of local produce, including bananas, pomegranates, pineapples, wax apples with a mixture of flowers and plants.

While the columns within the interior are decorative and celebrate central Taiwan’s agricultural prowess, what you don’t see is their functionality, which is covered by the closed ceiling. Within the attic space, there is an intricate network of wooden roof trusses and beams that have been installed to help stabilize the four-sided sloping gable roof that covers the station. The space above the eastern and western wings does the majority of the work with regard to stabilization as the central section, which features the iconic clock tower.

The central portion of the station tends to be the most architecturally significant section of the building as it protrudes from the roof in both the front and the rear. The space features a large front door as well as an open space at the rear where passengers would make their way through the turnstiles to the platform area. Protruding from the four-sided gable roof in the front, the central portion features its own two-sided roof with stone-carved floral and fruit displays at the apex and on the left and right.

The clock-tower rises up above the mid-section and features a four-sided copper roof of its own, with a spire reaching from the center.

While I’m not particularly sure if there was a clock in this space or not, the circular section in the middle facing outward from the building was replaced with the ‘Taiwan Railway’ logo at some point after the Japanese Colonial Era ended.

Once you’ve gone through the turnstiles to the platform area, one of the things you’ll want to pay attention to are the cast-iron columns along the platform space that maintain a similar approach to the Renaissance-style of architectural design. This is actually one of the only railway stations in Taiwan that maintains its original Japanese-era architectural designs, so when the area was restored, they made sure that extra attention was paid to these columns along the platform, which in some cases look like they’re straight out of Rome.

Speaking to the restoration of the building, it’s important to note some of the changes that took place within the station over the years. Today, if you visit, you’ll find the original wooden ticket booth, which has been well-preserved. That being said, as the city grew, the amount of passengers passing through the station increased. Thus, the eastern wing was renovated to feature a much larger ticket booth with offices for the station master and staff.

You can see the original train schedule displayed above this space, and there are currently informative displays in this space that help visitors understand the history of the building. The chairs within the western waiting space have been removed, and the space is now open with some educational displays added that help visitors understand the architectural design.

Taichung Railway Cultural Park (臺中驛鐵道文化園區)

A few years after operations at the century-old railway station were transferred to the newly constructed elevated station, the ‘Taichung Railway Cultural Park’ was officially inaugurated. Located next to the current railway station, the park not only includes the historic Taichung Station, but several other historic railway-related structures as well. That being said, the roll out of these historic structures, and their restoration continues to be a work in progress.

As I noted in my article regarding the role that Public-Private Partnerships (linked below) have played in the conservation of historic buildings in Taiwan, the Taichung Railway Cultural Park is almost a case study in its own right as the formation of the park has utilized a complex combination of OT (Operate-Transfer), ROT (Rehabilitate-Operate-Transfer) and BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) agreements with regard to the restoration and operation of the spaces within the park.

As part of the private partnerships operation agreement, the newly constructed elevated railway station also includes an impressive space on the first and second floors where visitors can enjoy local restaurants and purchase souvenirs from the city. As one of the city’s largest transport hubs, the railway station portion of the park can be a pretty busy place, but it has also become a popular spot for weekend pop-up markets, which are held along the historic train platform areas attracting quite a few visitors. It’s also become a great stop for foodies who can either enjoy a meal in one of the fifty-or-so restaurants within the park, or from some of the vendors within the market.

Similarly, if you’re a fan of the railway, it’s a great place to visit to enjoy the history of one of Taiwan’s oldest train stations, with exhibitions about its history, and even some historic trains that you can get on and check out.

Link: The role of Public-Private Partnerships in Conserving Historic Buildings in Taiwan

The culture park (currently) consists of the Second and Third Generation Railway Stations, the historic Taichung Rear Station (臺中後站), the Taichung Railway Freight Warehouses (二十號倉庫建築群), Taichung Station Railway Dormitories (復興路寄宿舍) and the Taiwan Connection 1908 railway path (臺中綠空鐵道). As mentioned above, though, not all of the buildings within the park have been restored and reopened to the public. Thus far, the historic train station, the rail platforms, the freight warehouses, and the green corridor have been opened. The railway dormitories and the rear station on the other hand are still in the process of being restored, and it’s unclear as to when they’ll have their official opening.

One of the best things about the park is that if you’re interested in the city’s history, you’re also a short walk from the historic Teikoku Sugar Factory Headquarters (帝國製糖廠臺中營業所), Taichung Park (台中公園), Taichung City Hall (台中市役所), the Taichung Prefectural Hall (台中州廳), and the Taichung Prison Martial Arts Hall. Similarly, the Taichung Confucius Temple (台中孔廟), Taichung Martyrs Shrine (臺中市忠烈祠) and the Taichung Literary Park (台中文學館) are all close by, and each of them originated during the Japanese-era, albeit with some caveats.

Unfortunately, even though the government has spent a considerable amount of money restoring buildings and making the railway park a really cool place to visit, the amount of information you’ll find available about it online is pretty weak. One of Taiwan’s biggest problems when it comes to tourism is that the government is willing to spend the money to develop these places, but when it comes to marketing them, especially to an international audience, they have absolutely no idea what to do. If you don’t believe me, feel free to click the link below to check out the railway park’s official website. I highly doubt you’ll be blown away by the effort that was put into its creation, or the amount of information that’s available.

Website: Taichung Railway Cultural Park (臺中驛鐵道文化園區) | Facebook Page

Hours: 11:00-21:00 (Monday to Friday), 10:30 - 21:30 (weekends and national holidays).

Getting There

Address: No. 1, Sec. 1, Taiwan Boulevard, Taichung (臺中市中區臺灣大道一段1號)

GPS: 24.141480, 120.680400

Whenever I write about one of Taiwan’s train stations, obviously the best advice for getting there is to take the train. Even though the historic Taichung Train Station has been put out of operation, both the station and the Taichung Railway Cultural Park are conveniently accessible via the newly constructed elevated Taichung Railway Station. So, if you’re coming from out of town, no matter if you’re coming from the north or the south, once you arrive at Taichung Station, you’re able to visit the culture park as soon as you exit the gates. That being said, if you’re arriving in town by way of the High Speed Rail, you’re going to have to transfer from the HSR station to the Xinwuri TRA Station (新烏日站), both of which are directly connected to each other. From there, you’ll make your way to Taichung Station, which is only four stops away.

If you’re in the city with a car, simply drive to Taichung Station, with the address provided above input into your GPS. There is a parking lot located within the lower levels of the station, so finding parking near the park is quite easy. Similarly, if you’re driving a scooter, you’ll find quite a bit of parking to the right of the historic station running perpendicular along Jianguo Road (建國路). It shouldn’t be too difficult to find a parking space, unless of course you’re visiting during a national holiday.

If you’re already in the city, but would like to visit, the park unfortunately isn’t accessible via the newly opened Taichung MRT, and it doesn’t look like it will be in the near future. So, if you want to make use of public transportation, the city has a number of buses that stop at both the front and rear sections of the station. The number of buses is quite expansive, so instead of listing them here, click the link to the Taichung Bus (台中客運) website below, where you can find the schedule and prices for each of the buses that service the station.

If you weren’t already aware, due to the lack of a proper subway system in the city for so long, the bus network has become quite expansive, convenient and reliable. If you’re in the city, taking the bus is probably one of your best options for getting around. If like most people, the bus network is a bit intimidating, never fear, simply open up Google Maps and set the Train Station as your destination, and the bus routes that you’ll need to take from wherever you are.

While living in Taiwan, I was fortunate enough to pass through the gates of the historic train station on quite a few occasions while it was still in operation. I’ve always been a big fan of Taichung, and there’s always quite a bit to do when visiting the city. In the near future, the city will be opening several new Japanese-era culture parks, so it’s likely that I’ll be making my way down there more often to check out some of these newly opened tourist attractions. Now that the train station has become part of a much larger culture park, it is a convenient place to check out, especially given that it is located next to the current station. If you’re arriving in town by the train, like so many millions of others have since 1905, you’re automatically treated to a birds-eye view of how Taichung has developed into a major city over the past century.

References

Taichung Railway Station | 臺中車站 中文 | 台中駅 日文 (Wiki)

臺中火車站 古蹟 (Wiki)

Taichu Prefecture | 臺中州 中文 | 台中州 日文 (Wiki)

Tatsuno Kingo | 辰野金吾 中文 | 辰野金吾 日文 (Wiki)

第二級古蹟臺中火車站整體修復工程調查研究及修護計畫 (臺灣記憶)

國定古蹟臺中火車站保存計畫 (文化部)

台中火車站 (國家文化資料庫)

臺中火車站 (國家文化資產網)

台中車站 (舊) (鐵貓)

Taichung Station Railway Cultural Park (臺中驛鐵路文化園區)

台中車站‧台灣唯一跨時代三代同堂的大車站 (旅行圖中)

臺中驛 (Wilhelm Cheng)

Departing from where it all started: Taichung Railway Station (Taiwan Fun)