For much of the world, 2020 was a year where most of us were forced to stick close to home for the collective health and safety of our families, friends and community.

As a result, international travel and tourism pretty much came to a screeching halt.

Here in Taiwan, thanks to swift government action, we were able to avoid much of the pandemic that enveloped the rest of the world.

But with a population of millions of travel aficionados, people in Taiwan turned to domestic travel in order to help stimulate the economy and relax their pandemic-weary bones.

Suffice to say, the nation’s numerous tourist destinations were packed all year long.

The pandemic has been a tragedy for so many around the world, but if there has been one positive, it is that it has given the people of this beautiful country an opportunity to reach a new-found appreciation for their homeland, something that I have been actively advocating for over a decade.

Taiwan’s outlying islands received more than their fair share of that attention, with tourists flocking all year to the Peng Hu archipelago (澎湖), Kinmen (金門), Matsu (馬祖), Green Island (綠島), Lambai Island (小琉球) and Orchid Island (蘭嶼).

Some of these islands however were completely unprepared for the sudden surge of pandemic-weary tourists, and had a difficult time coping; Orchid Island in particular, the least developed of Taiwan’s outlying islands, was overflowing with tourists all year long (including yours truly), but they did so with the smiles and friendliness that the people there are known for.

Link: Tourism Disrupts Life on Orchid Island (Taipei Times)

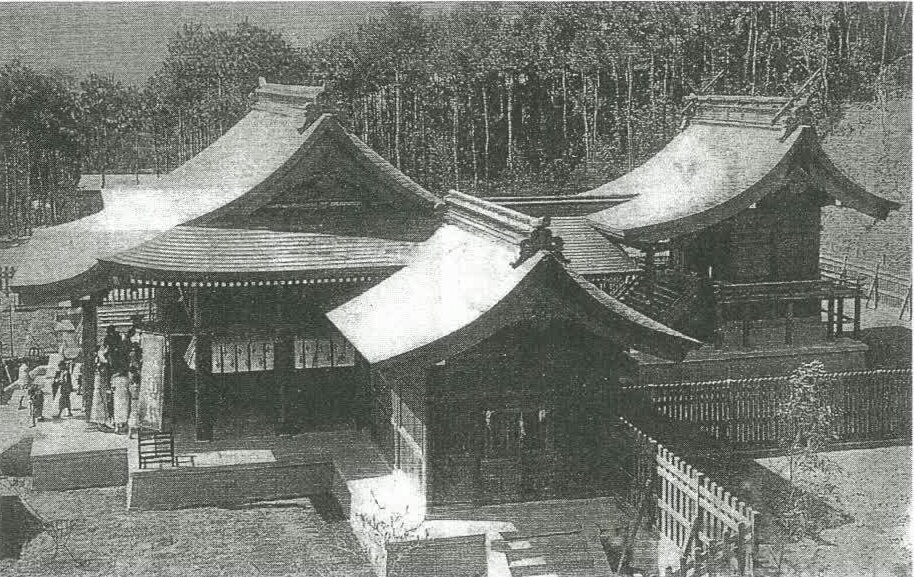

Orchid Island, otherwise known as “Lanyu” is Taiwan’s southern-most island and is the homeland of one of the nation’s smallest indigenous groups, the Tao people.

Known locally as Ponso no Tao (人之島) or the “Island of the People”, the 45 km2 (17 sq mi) volcanic island is located just off of Taiwan’s southeastern coast. The full time home to approximately 5,000 residents, the majority of whom are indigenous people, the breathtakingly beautiful island was cut off from the rest of the world for much of its history.

Times have certainly changed.

Geographically speaking, the island is home to eight mountains over 400 meters in height, and is surrounded entirely by coral. It is also home to numerous species of flora and fauna that aren’t found anywhere else in Taiwan, and is famously where you’ll also get to experience the annual migration of Flying Fish (飛魚).

While probably not endemic to the island, you’ll also find hundreds, if not thousands of free-roaming mountain goats, which seem to live very stress-free lives, and couldn’t really care less about the thousands of tourists coming to visit their island.

Even before the pandemic shut down international travel, Orchid Island was a rising star for domestic tourists, but it has always been a bit difficult to organize trips given its location and the lack of resources on the island.

Fortunately, planning a trip to Orchid Island has become a much easier process in recent years with tour groups offering packages that take care of all of the logistics.

For foreign travellers, getting to the island can be a little more difficult as there are only a few English-language guides currently available providing up-to-date information about getting there.

So, if you’d like to learn more about Orchid Island, how to get there and what to do while you’re there, I hope this travel guide will be of some assistance.

It goes without saying that Orchid Island is a stunningly beautiful island, and if you’re into snorkeling, diving and enjoying the ocean, this is one of those places in Taiwan that you should absolutely visit.

While there, you should take some time to learn about the amazing culture of the friendly indigenous people who live on the island, as well as their struggle to maintain their traditions and the hardships that they have faced ever since the world came knocking at their door.

Before I start, I just want to remind everyone that I’m not being paid to represent any travel companies, groups or guesthouses on the island.

I won’t be recommending any specific package tours or tour groups, but I will do my best to offer advice and links to places where you can find this information, in addition to giving advice on the practicalities involved with planning your trip.

The Tao People (達悟族)

You can’t talk about Orchid Island without first talking about its people, the Tao, who have lived on the island for almost a thousand years.

Taiwan is home to sixteen (currently) recognized groups of indigenous people, with a total population numbering around 800,000, or just a little over two percent of the nation’s total population.

The Tao however only number around 4,700, making them the smallest indigenous group, in addition to being one of the most unique.

Known as either the “Tao” (達悟族) or the “Yami” (雅美族), the ethnic Austronesian people have lived in isolation on Orchid Island for the better part of a thousand years.

Referring to themselves simply as “the people”, the Tao share loose genetic links with some of Taiwan’s other indigenous groups, but their customs and cultural practices are entirely unique.

How they ended up on the island remains a bit of mystery, but given that they are genetically closer to the native inhabitants of the isolated northern Batan Archipelago in the Philippines, it is suggested that (given their maritime prowess) they migrated to the island hundreds of years ago and made it their permanent home.

The maritime prowess that brought the Tao to Orchid Island is something that never really changed; The Tao have a deep connection to the ocean which forms the basis of their culture, customs and their spiritual beliefs.

For the Tao, the ocean was not just a means of survival, it was an extension of themselves, and the iconic fishing boats that they construct are one of their most important rites of passage.

Conservationists at heart, Tao culture is highly regarded for taking from the ocean only what is necessary for feeding the family.

Traditionally, Tao women have been responsible for the harvesting of taro and sweet potatoes, while the men were tasked with collecting fish.

While this may seem like a relatively simple division of labor, the Tao have strict rules that differentiate the kinds of fish that can be taken from the ocean.

Fish are cleverly divided into “good fish” (好魚) or “bad fish” (懷魚), known to the Tao as “oyoda among” and “ra’et a among” respectively. The so-called ‘good fish’ are reserved first for women and children, while the ‘bad fish’ are usually eaten by then men.

One could make accusations of sexism here, but if you think about it, this is actually a clever system of ensuring that overfishing never happened as fish were considered gifts from the gods and have always been held in high esteem in Tao culture.

The biggest gift from the gods to the Tao people are the ‘Flying Fish’, which are not only the good fish, but the ‘best fish’ and one of the main sources of sustenance for the people on the island.

For the Tao, their annual calendar is divided into three seasons, “rayon” (招魚祭), “teyteyka” (終食祭) and “amyan” (冬季), which are based entirely on the fishing seasons.

Rayon is the start of the year and the fish caught are used solely for ceremonial purposes.

Teyteyka is the busiest time of the year when the Tao catch the majority of the fish that are consumed throughout the year. This is also the time when fish are generally salted and dried so that they can be kept longer.

Amyan starts when the Flying Fish season ends and is generally the coldest and most dangerous time of the year for the Tao to be out on the water (due to typhoon season).

Given the importance of the Flying Fish to the Tao, there are ceremonies and rites of passage that take place annually, which are large occasions and have started to attract the interest of people from the mainland.

Living in isolation on their island for almost six centuries, the Tao were able to maintain their traditional way of life for much longer than many of Taiwan’s other indigenous groups, but when the Chinese and subsequently the Japanese arrived on the island, they were thrust into a world that was quickly industrializing, and had little power to resist.

Link: A Minority within a Minority: Cultural Survival on Taiwan’s Orchid Island (Cultural Survival)

The Japanese treated the island as a living anthropological museum and declared it off-limits to the general public. Known then as Kotosho (紅頭嶼 / こうとうしょ), the island and its people were closely studied by renowned Japanese anthropologist Torii Ryuzo (鳥居龍藏), who coined the term “Yami” after a linguistic miscommunication. The Japanese stationed military on the island and the treatment of the islanders was one of study, but also of indifference.

When the colonial era ended and the Chinese Nationalists arrived in Taiwan, the isolation of the island ended and military bases and prisons were constructed. This started an era of Chinese chauvinism, which forcibly imposed Han culture on the people of the island.

Sadly, Tao women were often used as comfort women for the armed forces stationed there, and when President Chiang Kai-Shek (蔣介石) visited the island, it is said that he was appalled at the living conditions, with free-roaming animals and houses that were built underground.

If the conditions under the Republic of China weren’t already terrible enough for the Tao, by the 1980s the government ‘claimed’ that a construction project on the southern portion of the island was going to be a new fishery port that would be of benefit to the people, but was actually just a waste dump for nuclear material from the power plants on the mainland.

The issue of the dump has been a contentious one for almost four decades, but the protests have for the most part been ignored, with only lip service paid to resolving the problem by successive governments.

Link: Debate on Orchid Island’s Nuclear Waste Disposal Continues Despite Compensation (The News Lens)

Given the recent decades of cultural imposition on the Tao, and after decades of Mandarin-only education, it shouldn’t surprise anyone to know that most of the younger generation are unable to speak their native language. Confounding the problem, once students have finished with primary school, they often end up leaving the island for higher education or job opportunities on the mainland.

Furthermore, the older generation has become so accustomed to the convenience of Chinese-language mass media that many local cultural practices have been replaced by television and the internet.

The majority of the Tao who remain on the island today find themselves constantly engaged in the management of guest houses and have become accustomed to using the internet to manage bookings and communicating with prospective guests.

Tourism may have brought economic opportunity to the island, but it has also had the detrimental effect of distracting those who are best fit to assist in the preservation of the language and culture.

Even though the issues facing the Tao people with regard to their traditional way of life persist, the Taiwanese government has initiated programs aimed at repairing the relationship between the mainland and the Tao. One such policy is to ensure that Tao language instruction is available in schools starting at the elementary level, and that there is enough public funding for cultural preservation.

Furthermore, given that the Tao language is closer to that of their genetic relatives in the Philippines than that of Taiwan’s other Austronesian indigenous peoples, cultural exchanges between the two have been initiated in an attempt to bridge the eight century gap between them.

The Tao might be one of Taiwan’s smallest indigenous groups, but knowledge and interest about their history and culture has spread throughout the country, with their iconography becoming even more recognizable than some of the nation’s largest indigenous groups.

Decades of disrespect and lack of understanding of indigenous culture is transforming into admiration and subsequent governments have promoted indigenous heritage as part of Taiwan’s self-identity.

There is still a lot of work to be done in preserving indigenous culture around Taiwan, but after decades of abuse, the situation on the island has finally started to show signs of improvement.

You might be wondering why I have an entire section dedicated to the Tao people, but don’t have any photos of them.

Well, even though many facets of local culture has changed over the past few decades, some of their traditions remain the same.

As tourists visiting Orchid Island, its important that you take note of some of the following taboos so that you don’t make a cultural faux-pas while enjoying the island.

Don’t take photos of the local people without first asking permission.

Don’t take photos of or enter any of the underground houses without permission.

Don’t enter any of the road side open-air pavilions without first asking permission.

Don’t touch or get into any of the fishing boats resting on the beach.

Don’t bring oranges or tangerines as gifts for the local people.

Don’t shout or act rashly while walking through any of the villages.

If you are viewing a traditional ritual, stay quiet and keep your distance.

The traditional boats of Orchid Island

Are they canoes? kayaks? What are they?

Like the Tao people themselves, their traditional fishing boats are also quite unique.

The boats, known on the island as “tatala” serve several different purposes.

Practically speaking, they are tools used for the collection of sustenance for people on the island.

Symbolically, they serve as one of the most important aspects of Tao culture, representing a thousand years of knowledge and wisdom.

Spiritually, the boats are thought of as an extension of the human figure, representing the earliest Tao males who made the voyage to the island, and are a symbol of heroism.

Unlike canoes, the Tatala aren’t crafted using a single tree trunk or log, but are crafted by shaping multiple planks of wood together with the help of wooden dowels and rattan. Still, the construction of these boats requires the combined effort of an entire clan.

Once the right tree is chosen, much of the work of stripping and cutting the log into shape is done in the forest. When that is done, it is carried back to the village to a workshop where the rest of the construction takes place.

The entire process is very ritual-oriented and requires at least twenty or more men to take part, taking turns carrying the wood across the island.

I’m not going to go into too much detail about the construction process of the boats, so if you’d like to know more, I highly recommend clicking the link below where there is a very detailed description by a researcher at the Taiwan Forestry Research Institute.

Link: The Tao People’s Tatala Boats on Lanyu (Dr. Hsiang-Hua Wang)

The boats, now an iconic Taiwanese symbol, take almost three years to complete and are constructed in different sizes with “tatala” (小拼板舟) for one, two or three men while “cinedkeran” (大拼板舟) are for six, eight or ten men.

Even though the length of the boats can vary, the shape generally remains the same with a design created to maintain stability on the ocean thanks to their high v-shaped arcs on the bow and stern.

Once the construction is completed, the decoration phase starts with the boats decorated with designs that feature the human figure, waves and the sun. Red, black and white paint is used for the decoration of the boats, all of which are created from natural sources including soil, sea shells and coal.

One thing that always remains the same with regard to the decorations on these boats is the “eye” (船之眼), which is a red, black and white shining sun. The eye is placed on the bow and is used to ward away evil spirits.

It just so happens to also act as one of the most important symbols for the Tao people.

Link: Fishing Boats of Orchid Island’s Tao People (Indigenous Boats)

For the Tao, building one of these boats is a sacred mission and a rite of passage; Owning one carries a heavy responsibility as well as bringing one a considerable amount of social status.

Suffice to say, these boats are expensive, require several years of work, and are subjected to elaborate launching rituals.

This is why tourists shouldn’t ever touch or enter them without permission.

When you’re on the island, take all the photos of these beautiful boats that you like, just remember to remain respectful of the local culture!

Weather and Climate

Despite Orchid Island’s short distance from Taiwan, the climate on the island is considerably different from that of the mainland.

The island is the only part of Taiwan where you’ll find a tropical rainforest climate, but similar to Taiwan’s tropical south-east coast, it’s generally quite warm year-round.

The average temperature ranges between a high of around 25 degrees and a low of 21, with a humidity of nearly 90% year-round.

Summers on the island are quite hot with a lot of sun and beautiful blue skies. However when typhoon season rolls around, the island experiences quite a bit of rain and wind and ends up causing a considerable amount of uncertainty for travellers.

Winters on the other hand tend to be gloomy as the windy and rainy weather often prevents the arrival and departure of ferries and planes.

When to go

Given that the Tao people have been living on Orchid Island for almost a thousand years, its probably best that travelers follow their lead when it comes to visiting the island.

The best time to visit the is certainly debatable, but there are a few things you’ll want to keep in mind when planning your trip.

The first is that if you visit during the early months of the year, your trip will coincide with the annual Flying Fish festival, which is the busiest time of the year for the local people and also when water activities will be limited for tourists.

February - March (飛魚招魚祭) - (Ceremonial) Flying Fish Season

June - July (飛魚收藏祭) - Flying Fish Season

August - January (飛魚終食祭) - End of the Season

The next thing you’ll want to keep in mind is that during Taiwan’s National Holidays and government mandated long weekends, the island fills to the brim with tourists, making it difficult to find accommodations or getting flights or the ferry to the island.

So, if you’d like to avoid the massive crowds of tourists, it’s probably best not to plan your vacation during a national holiday.

It’s probably also better not to plan your trip during typhoon season as you may end up getting stranded on the island for a few extra days with no possibility of returning to Taiwan as you wait out the storm.

Take it from me, I had an extra three days on the island thanks to a lingering typhoon that was blowing around south of Japan.

Likewise, during the winter, ferry and flight services are limited, so getting to the island and back can be a little more difficult for tourists.

If you’re asking me, I’d recommend that it is probably best to plan your trip sometime between April to July if at all possible. This way you’ll be able to enjoy the local culture and some of the best weather the island has to offer.

Orchid Island Destinations

On the map above, I’ve included the ports in Taitung as well as Kenting that you’ll use to get to the island. I’ve also included most of the tourist attractions on the island as well as some of the most popular places to eat.

One thing I’ll note is that Orchid Island has quite a few ‘rocks’ that are supposed to look like things. I’m not really a big fan of standing around looking at these kind of things, nor do I really like taking photos of them. So, even though I’ll introduce some of them below for your benefit, I won’t likely be including photos for many of them - because I honestly didn’t take any!

To better introduce the destinations you’ll want to check out, I’m going to split the island up into different geographic regions and list what you’ll find in each of them, so that you’re better able to follow the map.

One last thing, as I introduce each of the locations, I’ve done my best to use their local name and will provide the Mandarin translation beside it.

This might confuse some people so I’m assigning a letter to each location so that it corresponds to the locations on the map. The map is freely available to download, so if you’re planning a trip to the island, feel free to put it on your phone to use as a guide!

Jivalino (椰油部落) to Jimowrod (紅頭) - West Island

The western portion of the island is home to Jivalino village, also known as “Yeyou” (椰油), in addition to Jimowrod (紅頭村) or “Hongtou Village”.

Serving as the administrative centre of the island, you’ll find the local township office, health care centre, power plant, Kaiyuan Port, and Lanyu Airport in this area.

Even though the western portion of the island was the area developed the earliest by the Japanese and Chinese, it is also the area where you’ll find the most complete Tao settlements with traditional underground houses mixed together with modern cement housing.

It is also where many of the annual Flying Fish festival activities take place as well as where you’ll find some of the most scenic snorkelling spots, restaurants and guest houses on the island.

A. Honeymoon Bay (蜜月灣)

Honeymoon Bay is a beach just south of the main port and gets its name from the shape of the bay, which looks like a heart.

Even though there really isn’t very much to see here, if you have a drone, its probably worth a stop to take an arial photo of what looks like a heart from above.

B. Kaiyuan Harbour Lighthouse (舊蘭嶼燈塔)

The Kaiyuan Harbour Lighthouse is probably one of the first things you’ll see as you enter the harbour on the ferry. This lighthouse has been out of commission for quite a while but you’ll a staircase that allows tourists to walk up to the old lighthouse and check out the view of the harbour.

On one of the nights, I went to the lighthouse just before sunset to take photos and had a pretty good time. The sunset wasn’t all that great, but it was a great spot to check it out.

Jiraralay (朗島部落) - North Island

Jiraralay, also known as ‘Langdao’ (朗島) is the northern-most village on the island and is home to quite a few restaurants, a beach-side pizza place, and one of the only cocktail bars on the island.

It is also where you’ll find quite a few of the snorkeling and diving tours taking place.

The northern-most harbour is where you’ll find quite a few of the famous Tao fishing boats resting on the beach, and I wasn’t counting, but probably the highest percentage of roaming goats on the island.

C. Lanyu Lighthouse (蘭嶼燈塔)

The Lanyu Lighthouse is situated atop a mountain that features a really fun mountain road to drive up. The road gives great views of the ocean as it winds up the side of the mountain, and is a really great spot for watching the sunset.

The lighthouse is actually nothing special to see and it’s closed to the public, but the entrance to the lighthouse also acts as the entrance to the little non-existent lake that is advertised in local travel literature.

The lake, known as “Little Sky Lake” (小天池) has pretty much dried up and its not really easy to get to, so I wouldn’t recommend it.

Personally, I’d just ride up the mountain for the beautiful views of the ocean, which is something that I did on more than one occasion during my time on the island!

D. Tank Rock (坦克岩)

Tank Rock is pretty much what it sounds like, a rock that looks like a tank.

Like I mentioned above, nothing special.

There was a sunset happening as I passed by, so I took a photo.

E. Iraraley Secret Swimming Spot (朗島秘境)

The Iraraley “Secret” Swimming Spot isn’t really a secret at all.

It’s a popular spot for snorkeling, cliff-jumping and cave diving. The deep pool usually has quite a few aquatic friends swimming around and there’s even a deep cave that you’re able to swim through (if you’ve got oxygen), that takes you to the open ocean.

I enjoyed swimming here on several occasions and the cliff jumping was pretty fun.

Don’t go in your bare feet though, the coral is quite sharp.

F. Jyakmey Sawaswalan Cave (一線天)

This tunnel is a popular stop along the highway where you’ll often find people taking photos.

Known in Chinese as “Hongtou Rock” (紅頭岩), you’ll have to be careful as you scoot through as there are usually instagram models standing in the middle of the road posing and completely oblivious to traffic in addition to large gusts of wind as you pass through.

G. Jikarahem Cave (五孔洞)

The Jiharahem Cave is a popular stop just beyond the residential area of Jiraralay village.

Featuring at least five different caves, tourists can enter the largest while the second largest one is usually gated up as it’s used as a church, which actually looks pretty cool.

Jiranmilek (東清部落) - East Island

Jiranmilek, which is known as ‘Dongqing’ (東清) in Chinese is on the eastern portion of the island and is the area where most of the attractions you’re going to want to visit are located.

The area is also the ‘hippest’ location on Orchid Island with some pretty good restaurants, a night market, a 7-11, and most of the newest guest houses.

Staying in this area is a little more expensive than the other parts of the island, but you’re also going to be closer to everywhere you’ll want to visit as well as being blessed with beautiful sunrises every morning during your stay.

H. Lovers Cave (情人洞)

The Lovers Cave is one of Orchid Island’s most popular attractions, so when you arrive, you’re bound to see quite a few scooters parked along the road next to the trailhead for the short hike.

The trail to the beach is a well-developed cement path that you’ll follow for about ten minutes before reaching the rocky coast.

Just ahead you’ll find the Lovers Cave, which appears to be a head-shaped opening in the mountain, allowing for waves to come crashing through. The arched opening in the cave is the result of natural sea erosion and although the popularity of the area kind of confuses me, it is apparently a really great spot for watching the sunset.

I’ve seen some nice photos of the area on Instagram and drone footage from fellow blogger Foreigners in Taiwan, but I didn’t really stick around long enough to take many photos.

I. Iranmeylek Secret Cave (東清秘境)

Like the “secret” location mentioned above, the Iranmeylek ‘Secret’ Cave is probably the worst kept secret on the island.

I think it’s safe to say that pretty much everyone on Instagram knows about it.

The cave is located between the Lovers Cave and the town, but since there isn’t really any signage to send you in its direction, you have to figure it out yourself.

Essentially, there is a small road next to a breakfast shop on the outskirts of the town that will bring you to a make shift parking area, where you get off your rental scooter and walk down a path until you reach the cave.

Once you reach the cave there is a ladder that you’ll climb to get down to the beautiful swimming hole.

If you’re there for photos, one person should probably stay above for a photo looking down into the cave while the other does their best Instagram pose!

J. Iranmeylek Beach

You know all those iconic shots of the Tao people’s Tatala boats resting on the beach that you’ve seen all over the place?

Well, this is probably where they were taken.

Directly across from the 7-11 in Iranmeylek you’ll find a set of stairs that takes you down to the small rocky beach where you’ll find the boats sitting.

This is the spot where you’re likely to find photographers setting up tripods every morning before sunset to take one of those photos that you absolutely have to get while you’re on the island.

Another reason why this side of the island has become so popular!

One thing you’ll want to keep in mind (as mentioned above) is that there are quite a few local taboos with these boats, so even though you’ll often see the local goats sitting in them, remember not to touch them or sit in them to take photos.

K. Iranmeylek Bay (東清灣)

Iranmeylek Bay is a beautiful beach on the other side of the town and its fishing harbour. The bay isn’t really great for swimming, but its still a really nice place to get off the scooter, lay on the sand and dip your feet in the beautiful ocean water.

Unfortunately one of the sad things about this bay is the amount of garbage that has been collecting on the hill on the left side.

One of Lanyu’s biggest problems these days is the amount of garbage that has been accumulating thanks to the sudden popularity of the island with tourists. Given that this is also a popular hangout for the local goats, it sucks that this has become an issue.

L. Battleship Rock (軍艦岩)

Battleship Rock is an off-shore set of rocks that apparently looks like a battleship.

When the owner of the guest house we stayed at was explaining the various things to see on the island before we set out, she started laughing and said that “during the Second World War, the Americans were a bunch of dumbasses and kept bombing the rocks”, thinking it was a Japanese warship.

Then she paused for a minute and looked at me and said:

“Sorry, you’re not an American are you?”

M. Dragon-head Rock (龍頭岩)

The Dragon-Head Rock is one of those rock formations that you’ll find on the island that you can’t really miss. It’s big, its cool looking and some people think it looks like a dragon. Even though I’m a bit skeptical about the latter claims, the rock looks like a giant piece of modern art.

N. Elephant Trunk Rock (象鼻岩)

Of all the rock formations that you’ll see on your trip to the island, Elephant Trunk Rock is probably the one that actually looks like what they say it looks like. From a certain angle, you can really see the elephants head, which looks like it’s taking a drink from the ocean.

O. Lanyu Weather Station (蘭嶼氣象站)

The Lanyu Weather Station is situated atop one of the islands highest mountains and is an important place for scientific research about the local climate, in addition to the radiation levels emitting from the notorious nuclear storage facility at the base of the mountain.

Most of the station is off-limits, but apart from a steep hike to the top, you’re greeted with beautiful views of the south and western coasts of the island.

Even though there isn’t actually much to see, its a really nice spot to visit and the grassy plateau is a nice spot to take photos and to have a picnic!

P. Green Pasture (青青草原)

One of the most popular destinations on the island, the “Green Pasture” is often compared to Yangming Mountain’s Qingtiangang (擎天崗), but if you ask me, this area reminds me a bit more of the Quiraing on Scotland’s Isle of Skye.

The rolling grassy hills of the mountain with the cliffs and coast on the side make for a really great experience.

When you park on the side of the road, you’ll find a path that brings you to a nicely developed hiking path that is probably about a kilometer in length with the grassy fields on one side and high cliffs on the other.

If you’re visiting the island, this is one of the places that you absolutely have to go.

Q. Iranmeylek Night Market (東清夜市)

Referred to ironically by the locals as the “One Minute Night Market” (一分鐘夜市), this small night market is a recent addition to life on the island, but is a welcome one for a lot of people.

While you’ll find a few stalls selling foods that are popular in Taiwanese night markets, the main attraction at this one is the Flying Fish Fried Rice (飛魚炒飯), the Millet Donuts (小米甜甜圈), Taro Bubble Milk Tea (芋頭珍珠奶茶) and the various stalls selling grilled indigenous food.

You’ll want to keep in mind that dishes that are popular in Taiwan, like Fried Chicken (炸雞排) are all imported from the mainland, so if you really want to support the local population, you should try the flying fish, millet and taro dishes, which are all caught or grown locally.

The great thing about this small “one minute” night market (because it only takes a minute to walk through it) is the party-like community atmosphere that you get while visiting.

Sure, you might have to wait a while for some of the popular dishes, but you can also make new friends in the process.

Getting There

Orchid Island is a great time. Getting there however isn’t as much fun.

Given its remote location, you’ll have to first travel to either Kenting or Taitung, and from either location you’ll probably want to spend a night or two before hopping on a ferry or a flight to the island.

While the flight to the island is likely an enjoyable experience, most people elect to take the ferry, which can be a harrowing experience for those who aren’t used to spending time on boats.

If you don’t mind paying a little extra to save some time, I highly recommending taking the flight from Taitung.

If that’s not an option, the ferry is your only other choice.

You’ll just have to be prepared for a cabin full of travellers puking up whatever they’ve had for breakfast or lunch.

Plane

Taking a flight to the island from Taitung isn’t expensive and as mentioned above, you can save a lot of time (and a stomachache) by taking the scenic twenty-five minute flight.

The problem with flying is that the small planes only fit around nineteen passengers, and a certain amount of the seats are automatically reserved for locals, who fly back and forth on a frequent basis.

So even though there are a handful of flights everyday, the max number of tourists who can get on one of the daily flights is only around a hundred or more. This means that if you would prefer to fly to the island, you should book your tickets at least two months in advance, as that is the earliest you can book them.

The website for Daily Air, which flies back and forth between Taitung and Orchid Island is only in Mandarin, but its fairly straightforward.

If you have trouble booking flights through the website, you can give them a call and try to book your flight

Link: Daily Air (德安航空)

Unfortunately, travellers should be aware that if you are planning to fly during typhoon season (or if there are other weather issues), that there is a very high possibility of your flight being abruptly cancelled, leaving you stranded.

Flights to Orchid Island: 07:50, 09:00, 09:50, 11:00, 12:00, 14:00, 14:35, 16:00

Price: $1428

Flights to Taitung: 08:50, 10:00, 10:50, 12:00, 13:00, 15:00, 15:35, 17:00

Price: $1410

Links: Taitung Airport (台東航空站) | Lanyu Airport (蘭嶼航空站)

Ferry

Given the limited amount of flights to the island, most tourists elect to save a little money and take the ferry.

During the high season there are a couple of options for the ferry with one departing from Taitung and another from Kenting.

Generally speaking, there are two boats that depart each day, each with a capacity of around 250 passengers, so getting a seat is a little easier.

However, if you are planning on travelling to the island during the high season or on a national holiday, its still a good idea to book your tickets in well in advance.

And like the planes, if you are on the island and a typhoon is blowing around somewhere out in the Pacific, you may have to contend with the cancellation of ferry service, and having to stay an extra day or two.

The ticket office for the ferry opens about an hour before departure and its best to arrive early to pick up your tickets, especially if you’re picky about seating.

Depending on weather conditions, the trip should take anywhere between 150-180 minutes.

Before getting on the boat, you’ll probably see vendors walking around selling tablets that help prevent your stomach from exploding.

The tablets aren’t expensive, but they’re really important because the boat makes almost everyone onboard throw up. Even if you aren’t bothered by boats, the smell of two-hundred people throwing up around you is likely to cause some discomfort.

If you’d like to prepare for the onslaught of queasiness that you’re likely to experience before you arrive at the harbour, I recommend stopping by any pharmacy and asking for motion sickness medication, known around here as “暈船藥” (yùn chuán yào), which comes in chewable and drinkable options - and make sure you have enough for your return trip as supplies on the island run out pretty quickly!

You may also want to consider applying Pak Fah Yeow (白花油) or Green Oil (綠油精) ointments.

Traveling to Lanyu from Taitung’s Fugang Harbour (台東富岡漁港)

Address: #297 Fugang Street, Taitung City (臺東縣臺東市富岡街297號)

From Taitung Train Station (台東車站) you have the option of taking Taiwan Tour Bus (台灣好行) #8101 to the harbour or simply grabbing a taxi. Logistically speaking, the bus doesn’t come all that often and given that the taxi fare is only about 100-200NT from the station (or from downtown Taitung), its probably easier to just get a taxi.

Green Island Star (綠島之星)

Taitung - Orchid Island: 07:30, 13:00.

Orchid Island - Taitung: 10:00, 15:30.

King Star (恆星號)

Taitung - Orchid Island: 09:15

Orchid Island - Taitung: 13:00

Ticket Price: $1,200 (single), $2,300 (return)

From Kenting’s Houbihu Harbour (墾丁後壁湖遊艇港)

Address: #79-41 Da-guang Road, Hengchun Township, Pingtung (屏東縣恆春鎮大光路79-41號)

The Houbihu Ferry in Southern Taiwan’s Pingtung county is probably the most convenient ferry to take if you’re traveling from southern Taiwan.

The harbor is a short distance from both Hengchun (恆春) and Kenting (墾丁), so if you’re arriving by train or bus, your only option is to take a taxi to the harbor.

Service Period: April - October (每年10月至隔年3月停航)

Departing to Orchid Island: 07:30, 13:00

Departing to Houbihu: 10:00, 15:30

Getting Around

Scooter

If you ask a hundred people, they’re all likely tell you the same thing: The best way to get around Orchid Island is by scooter.

Scooters allow you to leisurely get around the island as well as allowing you to stop whenever and wherever you want, making them a much better option compared to the cars that are available.

Scooter rental on the island is quite simple and most of the tour packages that are available include a scooter rental in the price.

If not, renting a scooter ranges between $400-500NT a day for a 125cc scooter that can easily fit two passengers.

Note: If you’re in Taitung and you’ve got your own scooter with you, you also have the option of putting it on the ferry for an extra $300-400NT (one way).

There is limited space though, so you’ll probably want to check in advance if its possible.

Situated directly opposite Kaiyuan Port, you’ll find a couple of rental places, so if you haven’t pre-booked a scooter, you can shop around.

The prices are generally pretty much the same, so if you’re looking for a deal, you’re probably out of luck.

The good thing about this though is that they’re not going to cheat you out of a bunch of money like some of the rental places try to do in some of Taiwan’s other tourist locations.

They’re pretty laid back and save for signing a few forms, you’ll be riding around in no time.

For foreign travellers, you should either have an International Drivers License or a Taiwanese Drivers license to rent a scooter.

While it isn’t impossible to rent a scooter without a local license, you may find that if you don’t have one there could be some hassle.

Chia-Chia Scooter Rental (佳佳機車行)

Mei Ying Mei Scooter Rental (美英美機車出租行)

Yun-Chen Scooter Rental (蘭嶼雲晨機車出租車)

The scooters come with a full tank of gas and you’re expected to return it with one as well.

When you rent a scooter, you’ll be provided with two helmets and they’re obligated by law to tell you to wear them. As you pull out of the parking lot however you’ll notice everyone else scooting around without them and the police don’t really seem to care very much.

Car

If you’re traveling with a family, it’s possible to rent a car on the island, but most of the car rentals are done privately with the owner of your accommodations. Some of them will have a car rental service available and include the car in the price of your stay, but there aren’t that many, so you’ll want to do a bit of research on accommodations that offer this specific service.

With both car and scooter rentals, it’s important to remember that there is only one gas station on the island and that it is open from 7:00-20:00.

The station is often quite busy, so you’ll want to make sure that you don’t run out of gas on the wrong side of the island, especially after it has closed for the day.

CPC Corporation (台灣中油): #269 Yayo Village (台東縣蘭嶼鄉椰油村269號)

Accommodations

One of the most important decisions you make when travelling to the island is which area you plan on staying and what you actually plan on doing while you’re there.

As I mentioned above, the island is divided up into Jiayo (椰油), Jiraralay (朗島), Jiranmilek (東清), Jivalino (野銀), Jimowrod (紅頭) and Jiratay (漁人).

The western portion of the island, including Jiayou and Jiratay are generally the most developed areas and are home to Kaiyuan Port, the airport, 7-11, restaurants and the gas station.

You might see this and think that staying in the western area sounds really convenient, but to tell the truth it is also the furthest away from most of the destinations that you’ll want to visit.

It is also the area that was developed the earliest, so even though it seems convenient, it‘s also a bit older in terms of the quality of guest houses that are available.

This is also why you’ll find that the prices of guest houses in Jiranmilek (東清) on the eastern side of the island are the most expensive.

Jiranmilek is not only close to most of the destinations you’ll want to visit, but its also home to a burgeoning hipster community where you’ll find a night market and young people who have come back to the island to open businesses catering to the tourist industry.

The guest houses on this side are much newer and the community of guest houses is likely to continue to grow over the next few years.

The northern area of the island, Jiraralay (朗島) on the other hand has a mix of both older and newer guest houses and is probably an excellent compromise between the other two.

Staying on this part of the island allows you to get to the port area quickly, as well as all the destinations that you’ll want to visit.

While I’m not going to personally recommend a guest house, I will say that we chose one on the northern area of the island, which was a lot quieter than the ‘larger’ towns and allowed us to get back and forth between the port area for food and the eastern area quite easily.

When it comes to booking your guesthouse, especially during the high season, you’re going to want to do it well in advance to ensure that the place you want to stay is available.

Even though there are quite a few guesthouses on the island, they fill up quickly; Don’t think that you’re just going to be able to plan a spontaneous trip to the island and that you’ll be able to hop on a flight or a ferry, rent a scooter and have a place to stay.

It is also important to remember that you are booking a guest house on a secluded off-shore island, so don’t show up expecting to be checking into a luxury hotel - The amenities are basic and even though some of the rooms are nice, you aren’t there for luxury.

Below are some links that you can use to search for accommodations:

蘭色大門 - An excellent resource that has a list of all the guest houses on the island, separated by geographic location. Unfortunately, it’s only available in Chinese.

AirBnB - You’ll find quite a few of the guest houses listed on AirBnB, making the rental process much easier for those who can’t read Chinese.

Booking.com / Agoda - You’ll find quite a few of the guest houses on both of these sites with both English and Chinese.

If you don’t feel like doing all of the logistical work in planning your trip by yourself, there are tour groups that will help arrange a package tour to the island. These packages typically include transportation, accommodations and a scooter rental, with some possible additions that include snorkelling, diving, night tours, etc.

The price of the packaged tours is generally competitive, but if you’re on a budget, you can definitely save some money by arranging each of these things separately.

Orchid Island 3-Day Tour (KKDAY) (ENGLISH FRIENDLY)

Orchid Island 3-Day Tour (KLOOK)

Orchid Island Single Day Tour (UULANYU)

To look for packaged tours on your own, you can try searching “蘭嶼套裝行程” on your preferred search engine to see what comes up.

Snorkeling, Diving and other Activities

Orchid Island offers tourists various options for water-based activities and there are a number of professional divers and tour operators on the island available who are ready to take you out on the water for some fun.

If you’re arranging a packaged vacation on the island, you’ll often be offered a choice of a few activities, such a night tour or snorkelling.

If you haven’t pre-arranged some activities to fill your time, don’t worry.

When you arrive on the island, your guest-house will have a list of activities that they are able to help you with.

Snorkelling trips are typically a few hours long and will include a wet suit, mask and snorkel. Your guide will take you to a couple locations and and will pull you along with the help of a rope or a life preserver while also showing you some of the cool things under the ocean.

Diving trips on the other hand provide all of the necessary equipment and a guided tour. They will also include a crash course on diving as well as a video and photos of your experience.

Night tours and guided tours of the island can also be arranged through your guest house. Night tours generally include some views of flora and fauna that you wouldn’t notice on your own and maybe even some fresh seafood (like sea urchins), that your guide catches in front of you. Guided tours on the other hand provide a tour guide for an entire day who takes you on trip around the island, introducing everything you’ll want to see.

When it comes to swimming, you have to be a bit careful of the areas and beaches you choose as the ocean currents can often be quite strong. Some of the best areas for swimming include the Iraraley Secret Swimming Spot (朗島秘境) and the Iranmeylek Secret Cave (東清秘境) mentioned above.

If you are an experienced swimmer, you can even do some cliff jumping at the Iraraley Secret Swimming Spot.

Less experienced swimmers might find the Iranmeylek Cave a bit more to their liking as it is a lot more shallow and doesn’t have any waves or currents.

Note: If you plan on taking part in activities that involve swimming or walking along the coral beaches, you’re going to need a pair of shoes that you can wear in the water and also protect your feet from the sharp rocks on the beaches. These can be easily found in any outdoor activity store Taiwan, and they tend to be quite cheap if you’re buying them at Decathlon (迪卡儂), so make sure you pack a pair.

While the prices may vary between some of the guest houses, you should probably expect to pay the following for the water activities:

Snorkelling (浮潛): NT $450-500/person

Diving (體驗潛水): NT $2500-2800/person

Guided Island Tour (解說人員): NT $2000/person

Night Tour (夜釣小管): NT $700-800/person

The relative remoteness of Orchid Island has allowed the people living there to maintain much more of their traditional way of life than many of Taiwan’s other indigenous groups.

The island’s sudden surge in popularity with domestic tourism threatens to put that at risk as the local people juggle with maintaining tradition while also welcoming an influx of tourists.

Tourism might bring with it much needed economic opportunity to the island, but measures must to be taken to ensure that the Tao are able to sustain their traditional culture at the same time.

Practicing sustainable tourism can be difficult when people aren’t considering the big picture; The massive influx of tourists during the pandemic brought considerable economic opportunity to the island and its people who have opened up their homes and their hearts to all of us travellers.

That being said, more needs to be done to ensure that tourists visiting the island are able to learn more about the local culture, rather than simply enjoying the natural beauty of the island.

Orchid Island is a great place to visit and you’ll definitely have a great time while you’re there. As I mentioned above though, it is important to take some time out of your trip to learn more about the island and its people, while also doing your best to support local farmers, shop owners and restaurants.

Footnotes / Links

Orchid Island, Taiwan: A Detailed 2021 Guide (Spiritual Travels)

Orchid Island (Lanyu) 蘭嶼 (Foreigners in Taiwan)

Escape to Lanyu, Taiwan’s Remote Island Paradise (Occasional Traveller)

Wow! Lanyu, Orchid Island, Taiwan (Catherine Lee)

Tourism Disrupts Life on Orchid Island (Taipei Times)

The Six Villages of Lanyu (Lanyu.Land)

The Tao People (World Summit of Indigenous Cultures)

The Tao People’s Tatala boats on Lanyu (Taiwan Forestry Research Institute)

Orchid Island | 蘭嶼 (Wiki)

蘭嶼環島6大部落必訪景點 (旅行圖中)

蘭嶼旅遊攻略 (KKDAY)

蘭嶼三天兩夜 (KLOOK)

蘭嶼旅遊懶人包 (假日農夫愛趴趴照)