I’ve probably never mentioned this, but both my father and my grandfather are pretty highly-skilled carpenters. Growing up, I never really had much respect for what they did, especially when I got dragged out to one of their work sites to ‘learn the family trade’. This is because, where I live in Canada, it’s pretty much the norm to find houses constructed almost entirely of wood, so I never really considered what they did to be all that special - and what kind of kid wants to hang around a construction site anyway?

Looking back, I wish I took a bit more interest in what they were trying to teach me - not because I regret the decisions I’ve taken in life, but more so because I see a lot of their expertise in some of the articles I write about today. Similarly, after living so long in Taiwan among all of these concrete buildings, it’s easy to feel a bit nostalgic for those things that I thought were far too common in my youth.

Here in Taiwan, architectural design and construction techniques are concepts that have evolved considerably over time. If you’ve been here long enough, I’m sure you’ll probably have noticed that at some point someone came to the conclusion that the best way to protect people’s homes (from the harsh tropical environment) was to simply pour copious amounts of concrete, and hope for the best.

It wasn’t always like that though - As you might have seen from my various articles about the Japanese period, the architects of that era employed highly-skilled carpenters to assist in the development of the newly acquired colony. Granted, the environmental issues faced by the architects of that era were similar to what those today have to deal with, but they found a way to deal with it, and amazingly many of the wooden buildings that were constructed more than a century ago are in better shape than concrete structures half their age.

That being said, while there are quite a few of these heritage buildings that remain in great shape, and others that have received a bit of restoration - there are many that can be best described as ‘having seen better days’, and today I’m going to be introducing one of them.

In a recent article, I introduced Dashan Railway Station (大山火車站), a small train station in central Taiwan’s Miaoli county, which is nearing almost a century of operation. I explained in detail in that article how the small station located along Taiwan’s Coastal Railway (海岸線) is known as one of the Coastal Five Treasures (海線五寶), or the Coastal Three Treasures (海線三寶), depending on who you ask.

Links: Dashan Railway Station (大山火車站) | Xiangshan Railway Station (香山車站)

I don’t want to spend too much time re-hashing information that I’ve already provided, but each of these so-called “treasures” refers to century-old wooden train stations along the coastal railway line, three of which are located in Miaoli, while the other two are in Taichung. In each case, these historic stations are considerably smaller than what you’d expect from most of Taiwan’s other train stations, but have amazingly remained in operation for a century.

Given their age, each of these train stations has been afforded the designation as a protected heritage building, and at some point they’ll all (probably) receive the colloquial fresh coat of paint that they deserve, but as they’re set to celebrate their centennial in 2022, you’d be excused for wondering why they haven’t already received the attention they so desperately require.

Especially in the case of this particular station.

Of Miaoli’s so-called ‘Three Treasures’, Tanwen Station (談文車站) is probably in the worst shape of the bunch, but even though it looks as if it is falling apart, it has fortunately remained faithful to its original architectural design. Likewise, the materials used to construct the building almost a century ago remain in relatively good shape meaning that if you’re able to visit before they restore the building, you’ll get to see it in its original glory!

Coastal Railway (海岸線 / かいがんせん)

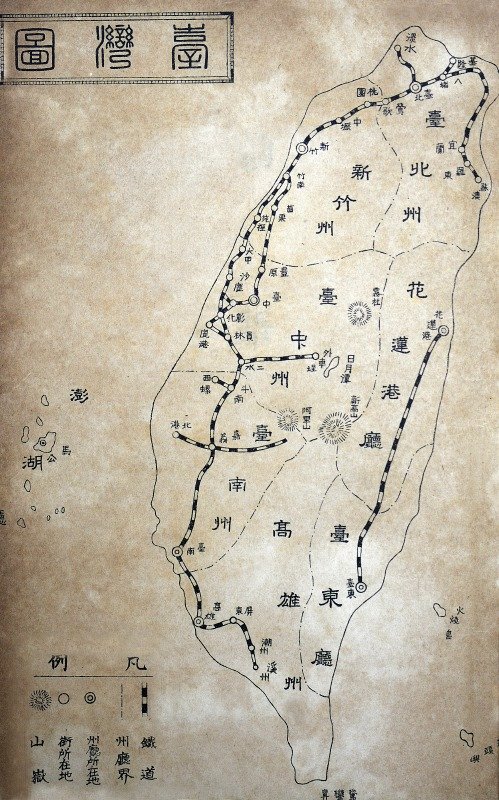

The history of the railway in Taiwan dates back as far as 1891 (光緒17), when the Qing governor, attempted to construct a route stretching from Keelung (基隆) all the way to Hsinchu (新竹). Ultimately though, the construction of the railway came at too high of a cost, especially with war raging back home in China, so any plans to expand it further were put on hold.

A few short years later in 1895 (明治28), the Japanese took control of Taiwan, and brought with them a team of skilled engineers who were tasked with coming up with plans to have that already established railway evaluated, and then to come up with suggestions to extend it all the way to the south of Taiwan and beyond.

The Jūkan Tetsudo Project (ゅうかんてつどう / 縱貫鐵道), otherwise known as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project’ sought to have the railroad pass through all of Taiwan’s already established settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄).

Completed in 1908 (明治41), the more than four-hundred kilometer railway connected the north to the south for the first time ever, and was all part of the Japanese Colonial Government’s master plan to ensure that Taiwan’s precious natural resources would be able to flow smoothy out of the ports in Northern, Central, and Southern Taiwan.

Once completed, the Railway Department of the Governor General of Taiwan (台灣總督府交通局鐵道部) set its sights on constructing branch lines across the country as well as expanding the railway network with a line on the eastern coast as well.

However, after almost a decade of service, unforeseen circumstances in central Taiwan necessitated changes in the way that the western railway was operated, with issues arising due to typhoon and earthquake damage. More specifically, the western trunk railway in southern Miaoli passed through the mountains and required somewhat of a steep incline in several sections before eventually crossing bridges across the Da’an (大安溪) and Da’jia Rivers (大甲溪).

Issues with the railway in the aftermath of a couple of devastating earthquakes created a lot of congestion, and periodic service outages in passenger and freight service when the railway and the bridges had to be repaired.

Link: Long-Teng Bridge (龍騰斷橋)

To solve this problem, the team of railway engineers put forward a plan to construct the Kaigan-sen (かいがんせん / 海岸線), or the Coastal Railway Branch line between Chikunangai (ちくなんがい / 竹南街) and Shoka (しょうかちょう / 彰化廳), or the cities we refer to today as Chunan (竹南) and Changhua (彰化).

Link: Western Trunk Line | 縱貫線 (Wiki)

Construction on the ninety kilometer Coastal Line started in 1919, and amazingly was completed just a few short years later in 1922 (大正11), servicing eighteen stations, some of which (as I mentioned above) continue to remain in service today.

Those stations were: Zhunan (竹南), Tanwen (談文湖), Dashan (大山), Houlong (後龍), Longgang (公司寮), Baishatun (白沙墩), Xinpu (新埔), Tongxiao (吞霄), Yuanli (苑裡), Rinan (日南), Dajia (大甲), Taichung Port (甲南), Qingshui (清水), Shalu (沙轆), Longjing (龍井), Dadu (大肚), Zhuifen (追分) and Changhua (彰化).

(Note: English is current name / Chinese is the original Japanese-era station name)

The completion of the Coastal Railway was incredibly signficant for a number reasons - most importantly, it assisted with moving freight between the ports in Keelung and Taichung much more efficiently, especially when it came to moving things out central Taiwan given that one of the stations was located at the port in Taichung. Although the railway was primarily used for moving freight back and forth, another important aspect was that the railway allowed for the smaller communities along the coast to grow and become more economically viable.

On that last point, the construction of the railway along the coast not only provided passenger service to the communities that grew along the coast, but it also allowed for entrepreneurs in those areas access to a modern method of exporting their own products for the first time. If you know anything about the relationship between Japan and Taiwan, one of the things that the Japanese absolutely love about this beautiful country is the wide variety of fruit that is grown here.

The coastal railway helped to ignite that passion with the coastal area in Miaoli exporting massive amounts of watermelons and other produce.

Tanwen Station (談文湖車站)

When the Western Coastal Railway opened for service, a number of railway stations simultaneously opened their doors, marking a historic day for passenger and freight service along Taiwan’s western coast, and more importantly improving upon to efficiency of the already existing railway. One of those stations was Miaoli’s Tanwen Station (談文車站 / だんぶんえき), which officially opened on October 11th, 1922 (大正11年).

Originally known as ‘Tanbunmizūmi Station’ (談文湖駅 / だんぶんみずうみえき), or ‘Tanwenhu’ in Mandarin, you might notice that at some point over the past century, one of the characters in the name seems to have disappeared. Currently referred to as “Tanwen” (談文), the character “湖” (mizūmi / hú / lake) was removed shortly after the Japanese-era came to an end.

The original name was derived from the fact that the low-lying area where the station was constructed was once home to a freshwater lake, part of an estuary of the nearby Zhonggang River (中港溪), which flows from the mountains and empties in the ocean.

That lake however seems to have disappeared, much like the character in the original name.

If you visit the station, you’ll likely notice that beyond the railway platforms there are a number of rice paddies, so I’m assuming that the lake that once existed there was at some point absorbed into the agricultural network set up by local farmers. Nevertheless, a few years after the Japanese-era came to an end, the Chinese Nationalist-controlled Taiwan Railway Administration officially renamed the station “Tanwen Station” (談文車站), removing mention of the ‘lake’ in the original name.

Unlike most the nation’s railway stations, Tanwen Station isn’t located within a town, village or even a community - It sits quietly along the Taiwan #1 Highway (台1線 / 縱貫公路), and it’s safe to say that most of the out-of-towners who pass by in their cars aren’t even likely to notice it. One of the reasons for this is because the station is also uniquely located down a hill just off of the highway. To reach the front door, you’ll have to walk down the narrow pathway, which is only really wide enough for scooters.

As mentioned above, one of the main reasons for the construction of the Coastal Railway was to alleviate congestion on the main rail line between Hsinchu and Taichung, but another reason that the railway could similarly offer freight access to the farmers along the coast, who most notably were in the business of exporting Miaoli’s famed watermelons to the ports in Taichung and Keelung for the market back in Japan.

So, if you’ve ever heard someone claim that the coastal railway was constructed to essentially get those precious watermelons back to Japan faster, they wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. If you’ve ever eaten a Taiwanese watermelon (or any fruit grown here), it shouldn’t really surprise you!

That being said, when you visit Tanwen Station today, you’d likely come to a conclusion (similar to my own) that that the station doesn’t really seem like it was set up in an optimal way for loading freight. Amazingly though, given the station’s location, and being the first stop along the Coastal railway, it was a prosperous one, given that neighboring Zaoqiao (造橋) was in the business of exporting acacia (相思木) and charcoal while Gongguan (公館) was producing red tiles (紅瓦) and Nanzhuang (南庄) was mining coal, all of which would have been loaded on freight trains at Tanwen to be sent south to the port in Taichung.

Having visited the station, I found it a bit difficult to believe that so much freight could have passed through there over the years. Taking a look at the satellite view on Google Maps however provides an explanation as to how this was actually possible - While the station itself was located in a low-lying area off of the (current) highway, another road was constructed on the opposite side of the tracks to facilitate the processing and loading of freight onto trains. While also quite narrow, the road would have serviced one-way traffic in and out, and looks as if it would have been an efficient set up with passengers entering through the station on one side and the freight being processed on the other side of the tracks.

The economic prosperity created by the station ultimately only ended up lasting a few decades as when the Japanese-era ended, so did much of the exporting of goods that went with it. The Coastal Railway continued its regular service, but as time passed, the number of freight trains running through the area gradually decreased, and today they have become almost non-existent.

Official figures state that in 2020, 24,242 passengers got off and on the train at Tanwen Station, which means that on average fewer than fifty people pass through its gates everyday. To offer a point of comparison, the next station over, Zhunan Station (竹南車站), records almost 15,000 daily passengers, which should go to show just how quiet it is at Tanwen Station.

Before I get into the architectural design of the station, I’m going to provide a brief timeline of events that took place at the station over the past century:

10/11/1922 (大正11年) - Tanbunmizūmi Station (淡文湖駅) officially opens for service.

3/10/1954 (民國43年) - The name of the station is officially changed to Tanwen Station (談文車站).

5/30/1976 (民國65年) - A head-on collision near the station results in 29 dead and 141 injured.

3/15/1991 (民國80年) - The station is reclassified as a Simple Platform Station (簡易站).

3/21/2008 (民國97年) - The station is recognized as a protected historic building (歷史建築).

06/30/2015 (民國104年) - The station switches to the usage of card swiping services rather than issuing tickets.

10/10/2022 (民國111年) - The station will celebrate its 100th year of service.

Architectural Design

Interestingly, when we talk about the stations that make up Miaoli’s Japanese-era “Three Treasures”, the architectural design of each of the stations differ only slightly. I suppose this shouldn’t be too much of a surprise given that they were all relatively small stations, each of which opened in the same year, meaning that they obviously saved some money when it came to architectural design and construction costs.

These buildings are about as formulaic as you’ll get with Japanese architectural design, but don’t let that fool you - the simplicity of these stations allows for some special design elements.

Obviously, as mentioned above, this station is currently in pretty bad shape compared to its contemporaries in Dashan and Xinpu, but even though the paint is chipping and parts of the station look like they’re falling apart, it is remarkably still in pretty good shape - especially when you take into consideration how old it is and that it has been completely open to the elements for a number of years.

Constructed in a fusion of Japanese and Western architectural design, one of the reasons these stations stand out today is that they were built almost entirely of wood (木造結構), more specifically locally sourced Taiwanese cedar (杉木). Another reason is because the architectural design fusion in the stations that were constructed during the Taishō era (大正) borrowed elements of Western Baroque (巴洛克建築), with that of traditional Japanese design.

To start, the station was constructed using the ubiquitous Irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of design, most often referred to simply in English as the “East Asian hip-and-gable roof” which more or less means that the building has a roof that is larger than its base. In this style of design, one of the best ways to ensure structural stability was to construct a network of beams and trusses within both the interior and exterior of the building. This allows the roof to (in this case ever to slightly) eclipse the base (母屋) while ensuring that its weight is evenly distributed so that it doesn’t collapse.

One of the areas where you’ll find that the dilapidated state of the station most interesting is that you can find parts where the ‘bamboo mud walls’ (編竹夾泥牆) are exposed, giving you a pretty good view of how walls were reinforced and insulated in Taiwan during the colonial era. This construction method was similar to what was commonly used back in Japan, but since bamboo was both cheap and abundant in Taiwan, the style was modified to form a lattice using bamboo, which is an impressively reliable building material.

Link: Bamboo Mud Wall (Wiki)

The roof was designed using the kirizuma-zukuri (妻造的樣式) style, which is one of the oldest and most commonly used designs in Japan. Translated simply as a “cut-out gable” roof, the kirizuma-style is one of the simplest of Japan’s ‘hip-and-gable’ roofs. What this basically means is that you have a section of the roof (above the rear entrance) that ‘cuts’ out from the rest of the roof and faces outward like an open book (入), while the longer part of the roof is curved facing in the opposite direction. From either the sky walk or the highway, you can get an excellent view of the roof as you descend either toward the building.

The roof was originally covered in Japanese-style black tiles (日式黑瓦), but like nearby Dashan Station, the tiles were replaced at some point (I haven’t found a specific date) with imitation cement tiles that remain similar to the original sodegawara (袖瓦/そでがわら), munagawara (棟瓦 /むながわらあ), nokigawara (軒瓦/のきがわら), and onigawara (鬼瓦/おにがわら) elements of traditional Japanese roof design.

One of the most notable ‘baroque-inspired’ elements of the building’s architectural design is the addition of the round ox-eye window (牛眼窗) located above the ‘cut’ section of the roof near the arch. If you’re descending the sky walk from the platform, its likely one of the first things you’ll notice as it is facing in that direction. The window helps to provide natural light into the station hall, and is one of those architectural elements that Japanese architects of the period absolutely loved.

The interior of the building is split in two sections, much like what we saw the former Qidu Railway Station with the largest section acting as the station hall while the other was where the station staff and ticket windows were located. Given that the station remains in operation today, only the station hall section is open to the public. That being said, the daily operation of the station is coordinated out of neighouring Zhunan Station (竹南車站), and the only employee you’ll find working there is most often found sitting within in a kiosk on the platform area. The station office is completely closed as is the ticket booth (the station shifted to card swiping for ticket purchasing) so you can’t even take a peek inside to see what the office looks like.

Today the station hall has been more or less stripped down and is pretty much empty, except for a few notices on the walls. The relative emptiness of the interior however allows you to appreciate the design of the building a bit more as you are free to walk around and examine everything closely, and at your leisure.

Personally, while I did appreciate that the station hall was empty, I thought its size, the open windows and the natural afternoon light made it a really comfortable experience, especially in comparison to the modern stations you’ll find throughout the country today.

One of my favorite aspects of the architectural design of the station is the L-shaped covered walkway located to the rear of the station hall and around to the side. As a son of a carpenter, this is one of the areas where I was able to really appreciate the traditional Japanese-style carpentry. Even though you can find these covered walkways included within almost all of the older Japanese-era stations, out of those that I’ve visited so far, this one is my favorite as you can better appreciate its age when you’re there.

Unfortunately, even though Tanwen Station is a protected historic property, it has certainly seen better days in terms of its condition. It’s unclear as to when the local government will ever pull the trigger on repairing the station, or having it completely restored - but if it doesn’t happen within the next few years, there might not be much left of the original building to restore.

One would hope that it would eventually receive the same treatment that the nearby Xiangshan Station has received, but only time will tell.

Still, I’m happy that I was able to check out the station in its original condition before it was fully repaired. If you feel the same way, and would like to enjoy a similar experience, I recommend planning a trip to the station within the near future.

Getting There

Address: #29 Ren-ai Road, Zaoqiao Township, Miaoli County (苗栗縣造橋鄉談文村仁愛路29號)

GPS: 24.656440 120.858330

As is the case with all of my articles about Taiwan’s historic railway stations, I’m going to say something that shouldn’t really surprise you - When you ask what is the best way to get to this train station, the answer should be pretty obvious: Take the train!

Tanwen Railway Station is one of the first stations you’ll reach after passing over into Miaoli County from Hsinchu. There are however a couple of important things to remember about taking the train: The first is that the station is located south of Hsinchu Station (新竹車站) on the Coastal Line (海線), and the second is that the station is only serviced by local commuter trains (區間車). What this means is that if you take an express train from Taipei or anywhere north of Hsinchu, you’ll have to switch to a commuter train once you’re there.

Be very careful about this, because the majority of trains leaving Hsinchu will take the mountain line (山線), and that’s definitely not where you want to be (on this excursion anyway). The ride to the station should take less than half an hour (25 minutes to be precise) from Hsinchu, and once you’re there you’ll be able to check out the station at your leisure before hopping back on the train to your next destination.

And if you’re asking for recommendations, I’d suggest stopping by the other Japanese-era railway stations in the vicinity such as Xiangshan (香山車站), Dashan (大山車站) and Xinpu (新埔車站) - or hopping back on the Mountain Line to check out Zaoqiao Station (造橋車站) and Tongluo Station (銅鑼車站).

For most weekend visitors, the station acts as a starting point for the Zhenghan Trail (鄭漢紀念步道), a relatively short hiking trail that provides excellent views of the coast and the Coastal Railway. It’s also a pretty popular location for railway photographers to take landscape photos of trains coming through the coastal landscape. If you’re interested in the trail, I highly recommend checking out the link below, which provides all the information you’ll need about hiking the trail.

Link: Zhenghan Trail 鄭漢幾年步道 (Taiwan Trails and Tales)

If on the other hand you’re in the area and you’re driving a car or scooter, but still want to stop by and check out the station, that’s okay as well. You should be able to easily find the station if you input the address provided above into your GPS or Google Maps. The station is located along the side of the road in Miaoli’s Zaoqiao Township (造橋鄉). If you’re driving a car, the station is next to a busy country road where parking is somewhat awkward, although not entirely impossible - if you’re only stopping by for a short time.

When you arrive, you’re free to walk around and check it out as it is pretty much an empty shell these days with riders having to walk across the sky walk to the platforms to swipe in and out.

References

談文車站 | Tanwen Station | 談文駅 (Wiki)

海線五寶 (Wiki)

細說苗栗「海線三寶」車站物語 (臺灣故事)

海線的老火車站 (二): 談文火車站 (Maggie’s Home)

『談文車站』苗栗縣定歷史建築~台鐵海線五寶之一的木造車站! (瑋瑋*美食萬歲 )

木造車站-海線五寶 (張誌恩 / 許正諱)

海線僅存五座木造車站:談文、大山、新埔、日南、追分全收錄!(David Win)