If it weren’t obvious enough already, a large portion of the research and writing I do about Taiwan revolves around the island’s five decade-long Japanese Colonial era. Over the past few years, I’ve worked to combine my photography with my writing and research skills to help tell the stories of some of the nation’s historic buildings, which is admittedly a great time to be into this kind of thing with the number of buildings that have been restored in recent years.

Writing about Shinto Shrines, Martial Arts Halls, Civic Buildings, Train Stations, and the dormitories provided to the civil servants of the era, I’ve covered a wide range of topics, but one that I’m especially proud of was a long research project that delved deeply into the Taiwanese government’s attempt to restore these buildings, and then seek private enterprises to assist in their operation. Coming from a university background in International Development, it’s important for me to see that the government isn’t just throwing bags of taxpayers dollars at these historic buildings with no clear, or sustainable vision for the future - Because, let’s face it, the reach of the government can only go so far - and attracting a steady stream of visitors to these historic buildings is one of the best ways to ensure that they continue to be saved, rather than bulldozed.

If you haven’t had the chance to read it, I highly recommend taking a look at the (sorry, very long) article I wrote about how the Taiwanese government is officially enlisting the participation of private enterprises to assist with the operation of some of these buildings, especially since it will offer a lot more context to what I’m going to be introducing below.

Link: The role of Public-Private Partnerships in Conserving Historic Buildings in Taiwan

Since completing the article above, I’ve naturally become interested in how those remaining buildings from that era are put to use - and with restoration projects taking place around the country at an astounding rate, the resurrection of these buildings has brought about a new level of awareness about the nation’s modern history. That history, which spans periods of Dutch, Spanish, Qing and Japanese-eras of colonial control, is something that was largely frowned upon in the nation’s classrooms during the Martial Law Period, but has within the last few decades become an important tool for helping the people of Taiwan become more aware of the history, where they come from, and more important has assisted in forming a Taiwanese identity.

For some people, a visit to these historic buildings can help them learn more about what it means to be Taiwanese. Some of the time though, people just want to sit in a coffee shop and relax - and thanks to places like Tokyo Bike Taipei, people can do just that while enjoying a bit of history at the same time!

Before I start, there are a few housekeeping notes that I’d like to remind readers about: The first is that I’m going to spend a bit of time introducing the historic building and what it was used for prior to it’s recent restoration and the coffee shop taking up residence within. The next thing I’d like everyone to keep in mind is that as always, I’m not getting paid for this post. I’ll briefly introduce the coffee shop, but I’m not going to be sharing photos of the menu or the coffee that I had while visiting - I’m not a food blogger and I’m writing this purely out of interest for the building - although I did enjoy my visit as I feel like the building is being put to pretty good use.

Shintomicho Market Dormitory (新富町食料品小賣市場員工宿舍)

Restored alongside the dormitory, the historic Shintomicho Market building was brought back to life as a cultural and tourist attraction in early 2017. An important part of the Bangkha neighborhood for at least nine decades, the building fell into disuse in the early 1990s and was abandoned for quite a while prior to the city recognizing it as a civic historic monument (市定古蹟).

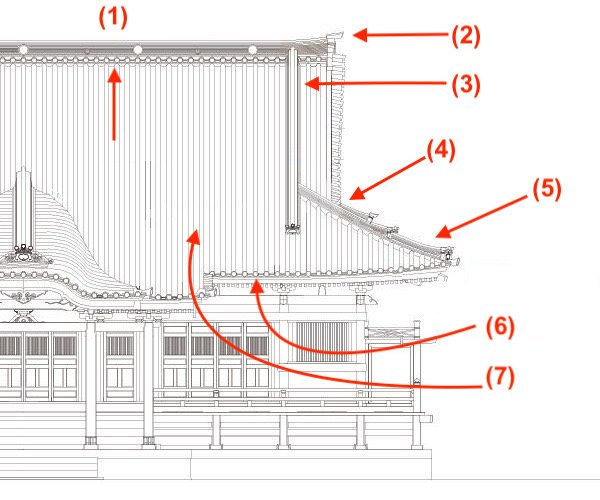

Walking through the artistically-designed building today, you’d probably find it hard to believe that it was constructed to house a wet market - especially if you’ve had experienced walking through any of Taiwan’s other traditional markets. Constructed in 1935 (昭和10年), which was pretty much the height of the Showa era (昭和) in Taiwan, the building was designed as a fusion of eastern and western architectural styles, but also displayed the modern approach to construction that the era is best known for.

To better explain, Taiwan was taken over during the Meiji era (1868-1912), followed by the Taisho era (1912-1926), and then the Showa era (1926-1989). Each of these so-called ‘eras’ is named after the emperor who ruled over the Japanese empire at the time. When the Japanese first arrived in Taiwan in 1895 (明治28年), the construction and development that took place was rudimentary, and later refined during the Taisho era. Initially, the infrastructure required for major construction projects was constrained, but as time passed by and the island was developed, it became much easier to construct more complex buildings. No where is this more prevalent than in the history of the nation’s historic railway stations, some of which (despite being a century old) are second and third generation structures. So, as the island developed, construction techniques were refined, and the Showa era thus became one of the more artistic with regard to architectural design.

Compared to modern wet markets, which are naturally dark, dank and smelly, the authorities at the time constructed this beautiful building with natural ventilation and natural light, making it the kind of place where vendors would compete ferociously to get a spot.

The newly constructed market brought with it not only prosperity for the local vendors, but a more sanitary experience where people were able to purchase daily necessities in an era where modern supermarkets had yet to appear. Attracting both Taiwanese and Japanese customers, the market would have been a cultural melting pot with freshly grown produce and meat. Suffice to say, like most buildings that were constructed in the late stages of the colonial era, prosperity would have been somewhat fleeting as the outbreak of the Second World War brought with it air raids by the allied forces and the decline of the local economy.

In the post-war era, the influx of refugees fleeing the Chinese Civil War created new opportunity for the market. One of the issues however was in order to actually open up shop within the building, vendors were required to obtain a license, something that would have been rather difficult for the local Taiwanese members of society given the political climate of the Martial Law period. Thus, the market started to expand from the original building to a wet market (which continues to remain in operation today) as it was easier for vendors to set up unlicensed stalls nearby. As Taiwan continued to develop over the next few decades, wholesale markets, supermarkets and hypermarkets started appearing across the country making it difficult for traditional wet markets to compete with lower prices.

As mentioned earlier, the market building was more or less abandoned in the early 1990s, and was left on its own for quite a while prior to being recognized as a protected civic monument. Years of abandonment left the building in pretty terrible shape, but it has been beautifully restored, and even though I’m not particularly a big fan of the way it’s used today, it’s a pretty cool place to visit if you’re in the area, especially for anyone visiting Longshan Temple (龍山寺).

The purpose of this article however isn’t to introduce the market, something that I might go into more detail in the future, but instead the Japanese-style dormitory constructed to the rear, where the TokyoBike Taipei coffee shop is located today.

Unfortunately, very little information has been published about the former dormitory, so I’ll be presenting a few facts based on the little information I could find and mixing it with my personal experience within the building and comparing it to some of the other buildings I’ve introduced in the past in order to offer readers a better idea of what you’d see during a visit to the building today.

Constructed alongside the market, the historic dormitory dates back to 1935, and to the naked eye appears similar to almost all of the other Japanese-era dormitories that I’ve introduced in the past. There is however a major difference about the building’s design that makes is different. Constructed to house the administrator of the market (and his family), the building also provided office space for the daily operation of the market. So, even though it might appear similar to other Japanese-era homes from the outside, the interior has some slight design variations that make it stand apart.

Officially classified as a ‘Single-Family Dwelling’ (獨棟木造日式建築), the size of the building was determined by the standard set in 1922 by the Taiwan Colonial Government’s building standards policy (台灣總督府官舍建築標準). In what would have been considered a low-ranking position in terms of the hierarchy of Japanese-era civic officials, the amount of space allotted for the construction of the building would have been about 83㎡ (25坪). In this case though, given that an office space for the administration of the market would have been included in the architectural design of the house, it would have made the amount of space somewhat cramped for the family living there.

Link: 台灣日式建築:官舍 —— 台灣樣.建築百科

While the building combined both private and public functions, the spatial design of the interior allowed for a comfortable separation between these two spaces, offering privacy to the families who occupied the space over the years. That being said, as (what would have been considered) a low-ranking official, the entrances to the house were notably different in comparison to its contemporaries.

For the family, the main entrance would have passed through the kitchen, where you’d have to pass through to reach the private space. For guests, or business-related visitors, a separate entrance would have offered access from a door to the right of the main entrance, offering direct access to the office space. Today, that ‘office space’ continues to be used as an administrative space for the coffeeshop, so it’s not actually open to the public.

In this particular case, what made the ‘family-side’ entrance different from others was that it was connected directly to the kitchen, which in most cases would have been a rear door to a garden. Passing directly through the ground-level kitchen brings you to a set of stairs where you walk up to the elevated private section of the house. Today, the coffeeshop maintains a similar design in that the barista’s bar as well as the kitchen is located in this ground-level area with the guest seating area in within the private area.

Despite some of the differences in interior design, its important to note that the basic design rule for traditional Japanese homes remains the same in that the building consists of the following three functional spaces: a living space (起居空間), a service space (服務空間) and a passage space (通行空間). Within each of these ‘spaces’ there can be a number of rooms, depending on the size of the building, but this one is somewhat basic, so it’s easier to describe.

Starting with the service space, you’ll find the kitchen (台所 / だいどころ), bathroom (風呂 / ふろ) and washroom (便所 / べんじょ). Interestingly, the bathroom and the washroom were located on opposite ends of the long ‘engawa’ (緣側/えんがわ) veranda between the living space and the office space.

Part of the ‘passage space’, the engawa is a large sliding-door veranda that could be opened up to allow some fresh air into the building as well as a space for the family to relax given that they didn’t have much of a front yard. The rest of the passage space in the building however is not as clearly defined as other Japanese-era residences, which only really consists of the space between the kitchen and the private living area and the kitchen and the office space.

Finally, the ‘living space’ may seem considerably different from what we’re used to by western standards but what the space essentially consists of is a two-room open space separated by something similar to a living room with the other being the bedroom. The first of these two spaces (座敷 / ざしき), and is essentially a living room where the family could spend time together. Within this space you’d find an alcove referred to as tokonoma (床の間/とこのま) and a chigaidana (違棚 / ちがいだな), which are both reserved for placing some decorative elements in the living space. During the Japanese-era, you’d likely find calligraphy, floral arrangements or simple artistic elements. Today, you’ll find one of TokyoBike’s beautiful bicycles on display.

Link: Tokonoma (Wiki)

The second section of the living space is the area reserved as the family’s sleeping space (居間 / いま). Essentially just an open space, save for the two alcoves against the walls, known as ‘oshiire’ (押入 / おしいれ). Within these two closet-like spaces, the family would store their bedding during the day, in addition to their clothing and other personal items. Today this narrow bedroom space is simply home to a couple of tables for the patrons of the coffeeshop.

TokyoBike Taipei

Originally located in the Minsheng East Community (民生社區), a block of social housing that was recently demolished by the city, Tokyo Bike Taiwan was forced to relocate after seven years of operation in it’s original location due to a long-planned urban renewal plan, which coincidentally also saw the demolition of the former Taiwan Railway Dormitories that I wrote about a few years back.

The dorm, which was initially occupied by Dadaocheng’s famed Hoshing 1947 pastry shop (合興壹玖肆柒) became available in late March of 2021 when the branch, which housed a traditional tea shop paired with the company’s pastries closed its doors after three years of operation. Even though the final Facebook post on Hoshing 88’s (合興八十八亭) page doesn’t offer a reason as to why the teashop went out of business, it’s safe to assume that a lack of business due to the COVID-19 pandemic was one of the deciding factors. Taiwan remained relatively safe for much of the pandemic, due to proactive policy decisions, but businesses around the country, much like the rest of the world, suffered immensely.

The opportunity to migrate from one historic area of the capital to an even more historic building was probably almost too good to be true for the owners of Tokyo Bike Taiwan, but as I described in my article about these Public-Private Partnerships, there is an official application process that has to be undertaken, and a fair advertising period has to be ensured so that the process is undertaken fairly and transparently.

Prospective renters have to come up with a business plan and undergo a long contract process prior to any agreements being signed. While the pandemic might have dealt the final blow to the building’s previous tenants, it could also have proved to be an opportunity for TokyoBike as competition was not likely to have been as fierce for the operational rights of the building. The application was obviously approved, and on December 21st, 2021, TokyoBike Taiwan officially reopened in the Shintomicho Market.

Note: I’m just making some assumptions here. I haven’t actually confirmed any of that.

Suffice to say, that is an oversimplification of the events that led up to the move to Wanhua.

This leads me to an important point - TokyoBike Taiwan is primarily a bike-selling and rental company that also provides general maintenance for the hip Japanese bicycles. You won’t see any of the bike sales taking place within the coffeeshop though, which begs the question: Where are all the bikes?

The bike showroom and the coffeeshop are separated, with the latter located within the beautifully restored Shintomicho Market building, known today as the “Taipei U-Mkt”, which offers a beautiful showroom on the second floor of the building as part of the rental agreement with the city.

The TokyoBike café features a menu of reasonably priced coffees, single-origin drip coffees, tea, sandwiches, hamburgers and appetizers that can be enjoyed within the cafe or for take out. Seating within the café is limited with only about four tables, a sofa, and bar-style seating next to the windows.

While I did enjoy my coffee when I visited the café, I have to say that I really appreciated the minimalist style design, which falls in line with the branding of ‘TokyoBike’, that officially follows a philosophy coined as “TokyoSlow,” combining ‘simplicity’, with ‘local art’ and ‘culture’.

Something that Taiwan’s hipster scene I’m sure really appreciates.

If any of this interests you and you find yourself in the area, then I recommend you stop by to check out the historic building and try some of the coffee or food they have available.

It's also a pretty good opportunity to let you know that if you visit the market or the coffeeshop that a good friend of mine just opened the Wanderland Bar within the Shintomicho Market where you can enjoy some cocktails and craft beer. As I’m posting this, I haven’t had the chance yet to visit, but I look forward to going soon, and I’ll make sure to stop by for a coffee as well!

Link: Wanderland Bar 萬華世界下午酒場 (Facebook)

Getting There

Address: #70, Sanshui Street, Wanhua District, Taipei (台北市萬華區三水街70號1樓)

GPS: 25.034700, 121.504860

If you plan on visiting this quaint little coffee shop, the best way to get there is to just hop on the Taipei MRT. I could spend a bunch of time telling you how to get there with a car, scooter, or Youbike, but in each of these cases, it doesn’t really make a lot of sense to take either of these methods of transportation.

The reason for this is actually quite simple - parking in Wanhua, especially near Longshan Temple is a notorious pain in the ass. There are, of course, some parking lots and roadside parking spaces nearby, but it’s likely that you’ll find yourself circling for quite a while before you find a spot. Similarly, the closest Youbike docking station is near the entrance to the temple, but the coffeeshop is at least a five-to-ten minute walk from there, depending on the amount of foot traffic in the area.

If you choose to make use of the fastest and most convenient method of travel, simply hop on the Taipei MRT’s Blue Line (板南線) and make your way to Longshan Temple Station (龍山寺捷運站). From there you’ll want to head in the direction of Exit 3 (3號出口) where you’ll find a small alley on the left. From the exit you just walk to the end of the alley and you’ll find the coffeeshop hidden in a corner by the old Xinfu Market (新富市場) and the Shintomicho Cultural Market (新富町文化市場). If you take the MRT, the walk to the coffeeshop should take less than a minute, and you won’t have to pay for or search for parking!

Website: TokyoBike Taiwan | Facebook

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday (08:30 - 6:00)

While in the Bangkha (艋舺) area, there are a number of things that you can do to pass your time. In addition to the coffeeshop you’ll find what’s known as the Bangka Big Three Temples (艋舺三大廟門) - Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺), Qingshan Temple (艋舺青山宮) and Qingshui Temple (艋舺清水巖) in addition to Bopiliao Historic Block (剝皮寮歷史街區) and several night markets.

As far as I can tell, since the opening of the coffeeshop within the historic dorm, it has become quite a popular spot for local Instagrammers and coffee lovers. Truth be told, I visited the during the week and was fortunately able to avoid the crowds, but a friend visited a few days later and commented that there weren’t any seats available and there were a bunch of people outside taking photos. If you’re planning a weekend visit, it’s probably important that you keep this in mind as the seating within the old dorm is quite limited.

The popularity of the coffeeshop is something that can hopefully last for quite a while, and I hope that its success is one that others might consider when applying to form a partnership with the government in one of these historic buildings. Putting these places to good use is one of the best methods of ensuring that they continue to be saved, allowing people to continue enjoying them for years to come!

References

台北最美單車咖啡廳「tokyobike」!落腳萬華新富町,獨棟木造日式古蹟建築 (Shopping Design)

Taipei's U-Mkt: A traditional Market Reborn (Taiwan Panorama)

新富町文化市場 (Travel Taipei)

新富町文化市場──古老市集的新生 (中央社)

新富市場 (國家文化資產網)