Given the amount of time I’ve spent researching the history of Taiwan’s Japanese Colonial Era, most readers are likely to assume that my interest is based on a mutual love for both Taiwan and Japan. Admittedly though, after all these years living in Asia, I’ve been almost everywhere else but Japan.

Like most young people, I was always interested in Japanese stuff, so when I got to university and needed to take a foreign language credit, it was a no-brainer: I signed up for Japanese class.

The thing is though, the class was over-booked and when I arrived on the first day, the classroom had a foul sour-like stench.

The first thought that came to mind was: Oh no! I’m in a class full of Otaku!

When the professor walked into the classroom he said: This class is overbooked and there are more people here than there are seats. Would anyone like to transfer to Mandarin? There were few takers. Why study Chinese? Anime wasn’t made in China.

I on the other hand, having a low tolerance for stink, raised my hand. The professor came over, presented me with a transfer sheet and I was on my way.

The funny thing is that after studying Mandarin for a couple of years at school in Canada, I then took an opportunity to continue my studies at Peking University. After that I spent some time on exchange at Xiamen University before arriving here in Taiwan, where I’ve been for the last decade.

Who knows where I’d be right now if I didn’t have such a low tolerance for stinky people.

I haven’t been avoiding Japan all this time - I’ve always wanted to go, but I’ve also happy when presented with opportunities to backpack through South East Asia, India, Nepal and go island hopping in the Pacific.

I figured that if I visited Japan that I’d fall in love with the place and every vacation after that would see me headed in the same direction. Coincidentally I think that already happened to my girlfriend, who has travelled to Japan a dozen times and speaks the language.

So when she informed me that as part of my birthday present that we’d be heading to Okinawa for a week, I instantly got excited.

It would be my first taste of Japan and I couldn’t wait to check out all the cool Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples while stuffing my face with ramen and sushi.

I was in for a bit of a rude awakening though.

Okinawa was actually nothing like I expected. Even though the islands are a part of Japan, they are in many ways quite ‘different’ from the rest of the country in terms of culture, language and religious practices - and for a lot of the people living there, being referred to as ‘Japanese’ is a contentious issue.

When you do a bit of reading about the history of the Ryukyu islands, you’ll find that there are valid reasons for this. When the islands were annexed by the Empire of Japan, the Meiji government at the time did its best to suppress the ethnic identity, culture and language of the local people in an attempt to assimilate them into Japanese society.

These attempts were obviously not looked upon favourably by the locals and while these policies did a tremendous amount of damage to the local culture, the arrival of the Americans and the decimation of pretty much everything on the island put that to a stop.

In the ensuing decades under American occupation, the people of Okinawa were given the opportunity to revive their language and cultural identity while also working to completely rebuild and redevelop their home.

Unfortunately even though the Okinawa of today has been completely redeveloped and shows surprisingly little evidence of the war, the work to revive Ryukyuan language and culture remains a work in progress.

Interestingly, as Okinawa redeveloped, most of the buildings lost during the war that were considered ‘culturally’ or ‘religiously’ significant, especially those of Japanese origin, were never rebuilt. So, if you’re travelling to the islands hoping to find a bunch of temples or shrines, you’re likely to be disappointed.

It shouldn’t really be all that surprising though, Shintoism, the Japanese state religion was never really that popular with the Ryukyuan people, who preferred their native folk religion and ancestral worship.

Never fear though, you’ll still be able to find a couple of Shinto Shrines and Buddhist Temples to visit if you have your heart set on a cultural experience.

There are a few things that you’ll have to keep in mind when it comes to Okinawa’s shrines and temples, which are essentially a lot like Okinawa itself - much different than the rest of Japan.

The first thing you’ll need to keep in mind is that on the mainland there are more than 80,000 Shinto Shrines, with the majority of them being associated with a religious network of shrines.

In Okinawa however there are only eight shrines in total, referred to as the Ryukyu Eight Shrines (琉球八社) and the only thing they are associated with is a neighboring Buddhist temple.

Link: Ryukyu Eight Shrines 琉球八社 (Samurai Archives)

Link: 琉球八社 (Wiki)

The lack of association with a network of shrines on the mainland essentially means that Okinawan shrines don’t receive much in terms of financial support and instead need to rely on the kindness of locals.

This isn’t entirely a terrible thing though as it has allowed the local people to take a bit of liberty with the architectural design of their shrines mixing in local Okinawan elements with traditional designs as well as allowing for the inclusion of more localized “kami” from Ryukyuan folk religion.

Additionally, of the eight shrines that exist today, almost all of them are located in the greater Naha area - This means that the further you travel outside of the capital, the less likely you are to find a shrine or a temple, even in the few other larger populated areas.

Today we’re going to be taking a look at the Futenma Shrine, one of the oldest and most important shrines in Okinawa, which just so happens to also be the largest and the prettiest of the bunch.

However, due to the length of this post (and the lack of in-depth English-language information available about the shrine), I’m going to be splitting it into two with this one focusing on the Shinto Shrine while the second post will focus on the Buddhist Temple located next door and information about how to get there.

Futenma Shinto Shrine (普天滿宮)

Dating back to the 14th Century, the Futenma Shinto Shrine has been a constant fixture of life in Okinawa for over six centuries. The shrine is considered to be the most important of the Eight Ryukyuan Shrines and over its long history, it has become a favorite among the locals and the (former) royal family.

Considering that it is one of the most important shrines in the whole of Okinawa, it shouldn’t be a surprise that every year on the first day of the Lunar New Year over 100,000 people walk through the main gate of the shrine to look for new year blessings. On every other day of the year though, you’ll find that the shrine is busy with locals visiting to pray for help finding love and having children. Likewise businesses will often make ‘official’ visits to make offerings looking to receive a divine blessing for prosperity and success.

If you’re visiting the shrine hoping to see a six hundred year old place of worship, you’re going to be a bit disappointed - The shrine that we see today was rebuilt in 2005 and looks pristine. If you’ve visited Japan though, what you should be able to respect about this shrine is its subtle differences from what has become the norm on the mainland. Futenma, and the others found in Okinawa follow tradition but they also make sure to add a bit of Okinawan charm to their design making the shrines stand out from what you may be used to.

Before we get into any of that though, let’s start by explaining the legends that were responsible for the construction of a shrine on this site in the first place:

The first legend tells of a young woman named “Megami,” (普天満女神) who despite being one of the most beautiful women in the area was pious and devout and instead of spending time with men, she spent her time locked in her room dedicating herself to spiritual pursuits. When her younger sister married, her husband’s curiosity one day got the best of him and he wanted to find out if Megami was really as beautiful as people said she was. When he took a sneak peak, she caught him, turned hysterical, left home and disappeared into the cave never to be seen again.

The next legend tells of a local couple who in order to survive worked several jobs - In particular the wife would walk every day from the Ginowan area to Shuri Castle where she worked as a royal maid. Every day after work on her long walk home she would stop in the area to pray. A popular Shinto deity named Kumano (熊野権現) took note of this and one day appeared to the woman as an old hermit and requested that she take care of a wrapped package for him. After several years the man hadn’t returned to take the package, but each day the wife would return to the same place hoping to find him. One day on her way home she stopped to pray and the god appeared to her and told her to open the package which was filled with gold making them wealthy and prosperous.

Even though the legends are a bit strange, through them we can better understand why Futenma Shrine has become such a popular place for local people who visit wishing to find love by the grace of Megami, now known as the “Futenma Goddess”, or good fortune thanks to Kumano.

Futenma Cave(普天滿宮洞穴)

The Futenma Cave, where it all started, is a 280 meter long limestone cave filled with stalagmite. Even though the cave is quite large, visitors are only able to access a front section that is about 50 meters in length while the rest of the cave is off limits to guests.

If you want to check out the cave, it is free of charge, but you’ll have to wait for one of the guided tours to take place. To sign up, simply walk in the door to the left of the main shrine, sign your name on the book and then patiently wait in the nicely air-conditioned room for someone from the temple to open the door to bring you in.

When you enter the cave, you will be led by one of the Miko’s (巫女) who will request that you follow the rules and refrain from taking photos inside the sacred area. While doing research for this post, I discovered that quite a few people didn’t bother to pay attention to that request and took photos anyway.

Admittedly, it would have been quite easy to take photos while inside as they’re not exactly chasing you around or keeping much of an eye on you, but I followed the rules and didn’t take any photos.

It may not be your religion or your culture, but it is still important to remain respectful of the local customs when you’re traveling.

The interior of the cave is quite impressive with large stalagmites and stalactites protruding from the roof of the cave and a small shrine nestled in among the rocks. The shrine, dedicated to one of the two gods found on the grounds is housed within a hokora (神庫), which you are only able to view from a distance.

The area is well-lit but you’ll also find quite a bit of natural sunlight entering the cave from some holes in the ceiling. While inside you’re free to walk around a bit, but there isn’t really that much to see, so your visit probably won’t take any longer than ten minutes.

The significant thing about the cave is that archaeologists have found quite a few interesting artifacts inside that tell of the history of the area - Some of those finds are put on display in a glass case near at the entrance of the cave.

History

Starting from humble origins, the Futenma Shrine that we see today was initially just a simple cave shrine where locals would come and pay homage to the cave lady.

A royal visit in the mid-15th Century by King Sho Taikyu (尚泰久王), who was well known for his patronage of Buddhism, cemented that from that time on, a much larger shrine would exist on the site.

Even though the temple is almost six hundred years old, its history hasn’t been well documented and if you’ve done any research about it you’ll find that certain dates and events aren’t really that well recorded. It also goes without saying that the shrine has had to be rebuilt on several different occasions, with two of those rebuilds happening within the last century. So even though the shrine is steeped in tradition and history, the actual structures that you see both above and below ground are all relatively new.

I’m not going to spend a lot of time going over every fine detail of the shrine’s long history, but below I’m going to provide a list of important dates that I think better explain some of the important events that happened over the past few hundred years.

1450 (15世紀中半) - King Sho Taikyu (尚泰久王) orders the construction of a shrine at the site of the Futenma Cave as it has become a popular place of worship among locals.

1868 (明治元年) - The Japanese government institutes a policy known as “Shinbutsu Bunri” (神仏分離) which orders the complete separation of Shinto from Buddhism, which were previously amalgamated and often inseparable. The policy also promoted Shintoism as the state religion and is remembered as a failed attempt to destroy the ‘foreign’ influence of Buddhism in Japan and its colonies.

1871 (明治4年) - The Meiji Government institutes a shrine ranking system and Futenma is classified as a “Mukakusha Shrine” (無格社) meaning that it is legally recognized but unassociated with the network of shrines on the mainland.

1945 (昭和20年) - The Shrine is destroyed during the Battle of Okinawa.

1953 (昭和28年) - Reconstruction of the Cave Shrine (奧宮) is completed.

1963 (昭和38年) - Reconstruction of the Haiden (拝殿) is completed.

1968 (昭和43年) - Reconstruction of the Honden (本殿) is completed.

1969 - 1970 (昭和43年-44年) - As is tradition with Kumano (熊野権現) worship, in order to receive the kami into your shrine, it first has to be ‘divided’ through a process known as ‘bunrei’ (分霊) or ‘kanjo’ (勧請) from a shrine at another location. A year of celebrations take place in order for Futenma Shrine to receive a new Kumano from the sacred Kumano Sanzan (熊野三山) mountains just south of Nara (奈良).

1973 (昭和48年) - The Shrine officially registers as a Religious Organization after Okinawa’s return to Japanese Control.

2004 (平成16年) - At the turn of the century, the shrine is in a bit of a state of disrepair due to years of typhoon and earthquake damage so a complete reconstruction of the shrine becomes necessary and is completed in 2005.

The Shrine Gate (鳥居)

The gate to the shrine is known in Japan as a "Torii" gate, which simply translated into English as a ‘bird perch’. These gates are typically found at the entrance of a shrine and their purpose is to demarcate the transition from the outside profane realm to that of a sacred one. This means that once you pass through the gate, it is time to stop joking around and to be respectful.

The Torii at Futenma is known as a Myojin torii (明神鳥居) which is one of the most common styles of Torii design and simply means that its upper beam is curved while the lower beam is straight.

Between the two beams you may notice a faded plaque that indicates the name of the shrine and reads “Futenma Shrine” (普天間宮).

Hung from the lower beam of the gate you’ll notice something known as the “sacred rope” or the “shimenawa” (標縄). The rope is thick and expertly braided and is decorated with “shide” (紙垂), which are beautifully cut paper streamers that are used in Shinto rituals. These sacred ropes are found all over Japan and have many different uses but here at the Shinto shrine it is used to help ward away evil spirits

Visiting Path (參道)

The “Sando” (參道) or “Visiting Path” is a common feature with Japanese Shinto and Buddhist places of worship and act as a path that leads to the Hall of Worship. The length of the path tends to vary between shrine with some being quite short while others can be several kilometers long.

The path at the Futenma Shrine is quite short and is simply a set of cement stairs with stone lanterns on either side that opens up to the Purification Fountain on the left and the Hall of Worship just ahead.

Purification Fountain (手水舍)

An important aspect of Shintoism is something known as the "sacred-profane dichotomy". In terms of this temple, the Torii gate at the entrance of a temple separates the world of the 'sin' from that of the 'sacred'. When you walk through the gate you are leaving the world of the profane which means that you should do so in the cleanest possible manner. So in order to ready yourself for entrance into the sacred realm you would have to do so with a purified body and mind.

As you approach the “chozuya” you’ll notice a handy sign next to it indicating the proper method of purifying yourself with a ceremony known as “temizu” (手水). The simple ceremony includes a few gestures that you’ll probably want to take part in if not just as a sign of respect, but because its hot in Okinawa and washing yourself with cold water is quite refreshing.

Pick up a ladle with your right hand, fill it with water and clean your left hand.

Swap the ladle to your left hand and then wash your right hand.

Swap hands again and pour some water into your left hand and take a drink.

Wash your left hand again and then tilt the ladle vertically so that the remaining water runs down the handle.

Administration Office (社務所)

The “Shamusho” (社務所) is directly behind the Purification Fountain and reaches almost as far as the Hall of Worship. The building is traditionally used to conduct the business of running the shrine and also acts as a place to allow the shrine personnel to rest. The building is also where you’ll go if the shrine is holding a lecture or if the priests are holding special events or prayer ceremonies that aren’t held in the Hall of Worship.

Traditionally the Shamusho is also where you’d go to purchase good luck charms, amulets, ema, etc. from the shrine, but at this particular shrine, they have that area directly connected to the Hall of Worship where you’ll find the young Miko priestesses working at a public counter where they not only sell the charms but also coordinate the cave tours with tourists.

I suppose the main reason for the separation of the Administration Office and the Public Counter in this case is largely due to the noise created by tourists waiting around for cave tours. The separation allows the priests to hang out in the administration office or give lectures without constantly being disturbed.

Stone Guardians (狛犬)

Shinto Shrines and temples in Japan are traditionally guarded by stone lion-dogs known as “Komainu” (狛犬). Thought to have originated in Korea, usage of these stone lion-dogs has become ubiquitous with places of worship throughout almost every country in Asia where they typically appear in front of a temple and are meant to help ward off evil spirits.

Okinawa being Okinawa though, the traditional stone lion-dogs that guard the shrine have been replaced with the Shisa (シーサー), or “shi-shi” (獅子) in the local language. The Shisa lions, I guess you could say are a distant cousin of the Komainu and are prevalent throughout the Ryukyuan islands acting as not only the guardians of temples and shrines, but also homes and businesses as well.

The Shisa first appeared in Okinawa in the 15th Century and in the years since the lion has transformed into an image that symbolises the cultural identity of the people of the Ryukyuan islands and there are many legends in the area that tell of how they arrived.

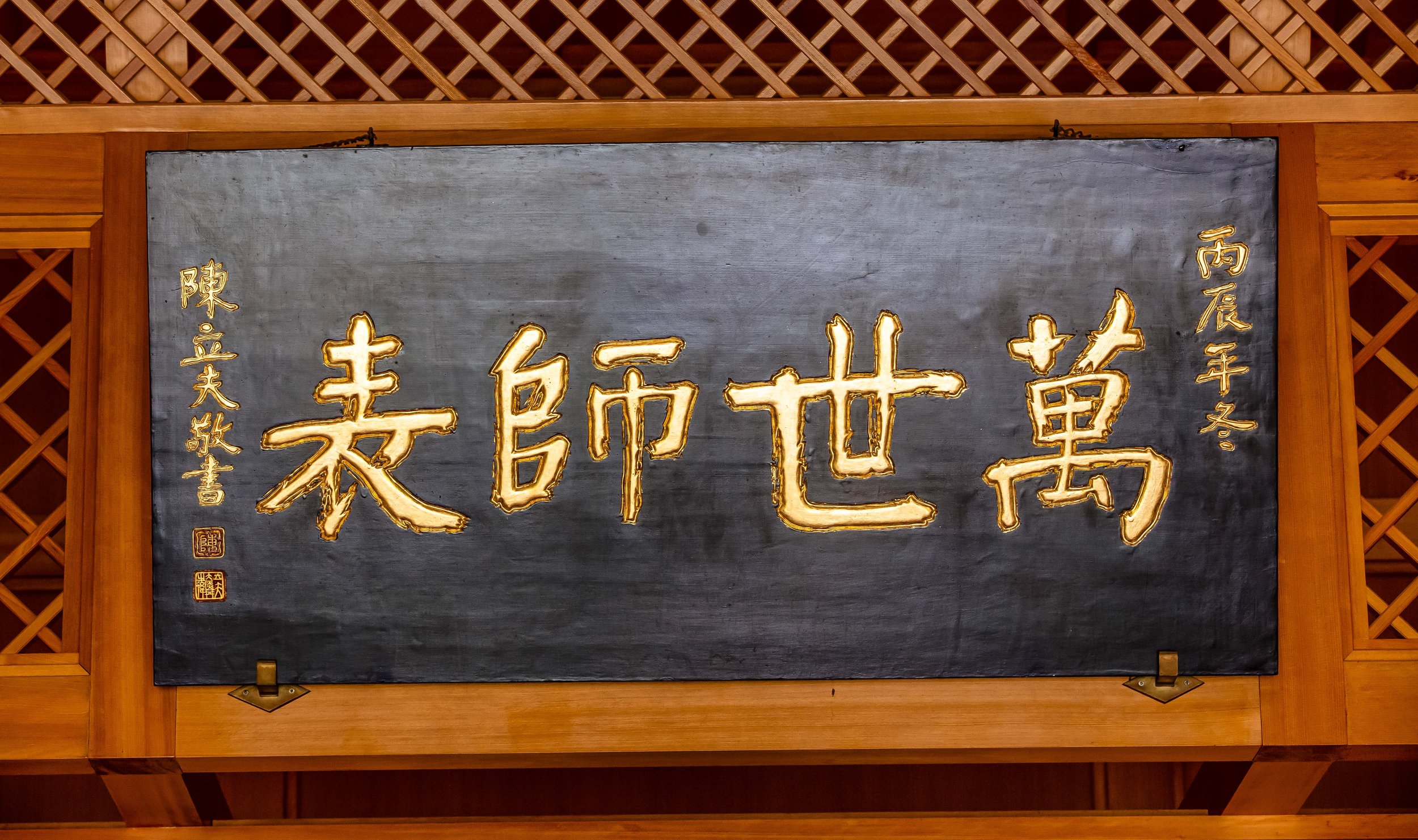

Hall of Worship (拜殿)

For most visitors, the Hall of Worship or the “Haiden” is the main attraction of a visit to the shrine and is the place where most of the local people will head once they’ve finished at the purification fountain.

From a distance, the Hall of Worship is extremely picturesque and the closer you get the more you’re able to fully enjoy the finer details of its design. Specifically, there are quite a few elements of the halls design where you’re going to notice strikingly distinct differences from what is the norm on the mainland.

The first major difference is that that the shrine was constructed using a combination of cement and wood. My original impression was that they took some shortcuts with the construction of the shrine, but would later find out that I was mistaken. The reason for this combination is quite simple - Okinawa is constantly under the threat of typhoons making landfall during the summer. In fact, the shrine was was reconstructed in the late 1960s had to be completely replaced less than four decades later due to damage caused by extreme weather. So when they rebuilt the shrine again in 2004, they made sure to construct it in a way that kept with tradition, but also hoping that it could last a bit longer this time.

Another local contribution to the shrine is the Okinawan limestone that was used to construct steps and the elevated walkway that leads up to the front door of the hall and around the sides.

The biggest difference however is the beautiful red tiled roof that has become quite synonymous with the architecture found on the islands. The red tiles, known as “Aka-Gawara” (沖繩赤瓦) are created using a black soil found in the south of Okinawa which in addition to the elaborate firing process produces the distinct colors.

The combination of the red tiles and the beautiful blue Okinawan sky makes the shrine shine in the sunlight and at the same time makes some of the shrines on the mainland look a bit dull.

Link: Ryukyuan Architecture in Zamami: Red Tile Roofs (The Zamami Times)

Most of what you’re going to want to see from the Hall of Worship is on the exterior, but if you’d really like to walk up to the doors to take a peak inside, you’re going to want to follow tradition and first follow a few steps which will impress the locals.

First you’ll want to walk up the steps to the wooden box in front of the main doors. You can drop in a small donation (there’s no set amount), then clap your hands twice to alert the Kami of your presence, then with your hands clasped together, bow your head and make a wish. When you’re done, its tradition to bow. From there you can approach the glass windows at the main door and take a peak inside of the shrine room to see whats happening.

The interior is rather simple with a shrine in the middle and a mirror placed on top of it. There are meditation cushions lined up in front of the shrine and there is a drum to the right. The interior doesn’t really have much going on, so if you peak inside try not to take too long because others might be there wanting to pray and you may be blocking their line of sight with the kami enshrined inside.

Main Hall (本殿)

The Main Hall or the “Honden” (本殿) is the literal beating heart of any Shinto Shrine and is where the kami is enshrined. It is a space that is considered so sacred that it is off-limits to anyone other than the priests who reside at the shrine. Contrast to what you’ll find at a Buddhist temple, where the statues of Buddha’s are situated within a shrine and are easily approached, in a shrine like this, a “kami” is only ever placed within a Honden and is physically represented in the Hall of Worship by a mirror.

The Honden is located directly behind the Hall of Worship and can be reached only by walking through one of the two sliding doors in the hall and then up a set of stairs to the small shrine.

Even though the area is off limits, when you take a tour of the cave, you’ll be able to check it out from the entrance to the cave. It is located on a small hill on top of the cave at the rear of the Hall of Worship.

In the second part part of this post I will introduce the beautiful Futenma Buddhist Temple which sits directly next to tis shrine as well as pertinent travel information that you’ll need to make your way to the shrine. When I’ve posted the second part, I’ll update here with a link. I hope this post helps travelers understand this beautiful shrine a bit more than the scattered bits of information you’re able to find elsewhere on the net.

If you’re visiting Okinawa, I highly recommend stopping by this beautiful shrine.