Throughout history, Taiwan has been an island of ‘gates’ and if you’ve followed, or researched the history of the country enough, you’re probably already aware that every major town - Taipei, Hsinchu, Chiayi, Tainan, etc., all had their own gates. Useful not only for demarcating territory, the gates were instrumental in protecting its citizenry, as well. Using Taipei as an example, today, if you travel around the city, it’s highly likely that you’ll encounter the ‘Beimen’ (北門), ‘Ximen’ (西門), ‘Nanmen’ (南門) and ‘Dongmen' (東門) areas of the city. These areas signify the historic locations of the northern, western, southern, and eastern entrances of the city.

Even though the original walls that once enclosed and protected the city were demolished more than a century ago, we still recognize districts of the city using these terms, and the same goes for other major cities and towns around the country, where you can trace the history of these historic walled cities.

When the Japanese first set foot in Taiwan in 1895, the ‘walled’ cities that had been constructed prior to their arrival were far too small for what the colonial government envisioned as a proper city, so they were promptly torn down. In most cases, the decorative gates that went with the walls were torn down as well, but, we’re fortunate that in some areas, the gates were preserved for their architectural beauty. A few examples of these remaining gates are Taipei’s North Gate (北門), Hsinchu’s East Gate (西門), Tainan’s East Gate (大東門), little East Gate (小東門), South Gate (大南門), and in the southern town of Hengchun (恆春), the only former walled city in Taiwan where all of its original gates remain standing.

When it comes to Chiayi, though, a number of factors contributed to the walls of the historic city of Tsulosan (諸羅山) coming down. First, though, before I talk about their destruction, let me start by telling the story of their creation: In 1727, Liu Lang-bi (劉良璧), a local magistrate, ordered the construction of a walled city, surrounded by four gates to help protect the residents of Tsulosan. Today, we usually just refer to these gates using their cardinal directions, but they also had more formal names as well. The Eastern Gate was known as “Chin Shan" (襟山), the Western Gate was "Tai Hai" (帶海), the Southern Gate was ”Chung Yang" (崇陽), and "Kung Chen" (拱辰) was used for the for the Northern Gate. However, the Qing at the time weren’t as invested in protecting the area as much as they were other areas of Taiwan, so unlike the stone walls that protected Taipei, Tsulosan’s walls were constructed with sharpened bamboo, in a technique that was known as ‘piercing-bamboo walls’ (刺竹). Those walls would come in quite handy a few decades later as they assisted the residents of the town in resisting invasion during the Lin Shuangwen Rebellion (林爽文事件), which to say the least was an historic event of epic proportions, and would ultimately result in the Qianlong Emperor (乾隆皇帝) bestowing the name ‘Kagee’ (嘉義) on the city, a name that is still used today.

The demise of the walls and the city gates, however, came much later during the Japanese conquest of Taiwan in 1895. The residents of Kagee valiantly resisted the Japanese military, but with advanced artillery, the residents didn’t stand much of a chance. The campaign to take control of Kagee resulted in the destruction of the North Gate, and severely damaging the others. The other two gates, sadly, came down just a few years later, in 1904 and 1906, when two massive earthquakes devastated the area.

That being said, when the Great Kagi Earthquake (嘉義大地震) occurred in 1906 (明治39年), very little of what had been constructed in the original walled city was left standing as most of the town was reduced to rubble.

Despite just a few years earlier shelling the town with artillery, in the aftermath of the earthquake, the colonial government did a pretty good job endearing itself to the residents of the town. The government quickly got to work coordinating humanitarian efforts, rescuing and treating the injured, but also for how they dealt with the thousands of dead bodies in the city, which, due to local taboos, the Formosan residents were afraid to disturb. With a clean slate, as a result of the devastation of the earthquake, the colonial government saw the opportunity for reconstruction, and immediately developed an ‘urban correction’ (市區改正) plan that would develop the town into a city, and one that was worthy of the government’s ambition for the area.

Amazingly, in just a few short years, Kagi would transform into one of Taiwan’s economic powerhouses, bringing riches to its citizens on a scale that few could have ever imagined.

One of the important things to keep in mind about Kagi was that it was strategically located in one of the most ‘tropical’ areas of the Japanese empire, and thus it was able to became one of Taiwan’s most prominent areas for the cultivation of sugarcane and various types of fruit, most notably the pineapple, which was a prized commodity for the Japanese. If the tropical nature of the plains weren’t already significant enough, when massive deposits of precious cypress in the mountainous areas near the town were discovered, Kagi became a veritable gold mine for the fledgling empire, which above all else, coveted the treasure trove of natural resources that Taiwan had to offer.

Suffice to say, the extraction of these natural resources became such an important industry that at massive expense, a ninety kilometer-long branch railway, which would become the highest elevated railway in the Japanese Empire, was constructed just to transport all of the timber out of the area.

That railway, known today as the Alishan Forest Railway (阿里山森林鐵路) has become one of Taiwan’s most iconic tourist destinations, and it all starts in the beautiful city of Chiayi, including what has also become one of the most iconic Japanese-era railway stations, Beimen Station (北門車站).

Obviously, I wouldn’t have spent so much time introducing the historic gates above if there wasn’t a good reason. If you take a look at the Japanese-era map of Kagi above, with the walled city illustrated on top, you’ll understand why. During the Japanese-era, Kagi was separated into several districts, which split the town up based on where the gates once existed. There was Hokumon District (北門町 / ほくもんちょう), Tomon District (東門町 / とうもんちょう), Seimon District (西門町 / せいもんちょう), and Nanmon District (南門町 / なんもんちょう). If you can’t understand Japanese or Chinese, you may be wondering why the names of these districts are significant, so before I start introducing the station, I should probably offer a brief language lesson to help clear up any confusion.

Below, I’ll introduce the names of each of the four historic gates with their original Taiwanese, Mandarin Pinyin, and the Japanese name, where I’ll think you should be able to see similarities between each of them, despite the fact that they’re three different languages. It’s also important to note that even though these gates had their own formal names, the names using the cardinal directions also apply to the gates in every walled city in Taiwan.

North Gate (北門 / Pak-mng / Beimen / Hokumon)

East Gate (東門 / Tang-mng / Dongmen / Tomon)

South Gate (南門 / Lâm-mng / Nanmen / Nanmon)

West Gate (西門 / Se-mng / Ximen / Seimon)

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, let’s clear up something might also confuse people. If you’ve read this far, you’re probably well aware that I’m going to be introducing a train station in Chiayi, however, it’s important to note that Chiayi’s ‘Beimen’, otherwise known as ‘Hokumon Station’, wasn’t the only train station with that particular name in Taiwan.

Taipei was also once home to a ‘Hokumon Station,’ close to where the Taiwan Railway Museum (臺灣總督府鐵道部) is located today. Just across the street from the city’s iconic North Gate, today, you’ll find the underground ‘Beimen MRT Station’ (北門捷運站), which maintains the name of the original station, and the Japanese-era district where it was located. If you’ve landed here looking for information about how to get around Taipei, or the MRT station, I’m sorry, you’re in the wrong spot.

Unfortunately, this is common issue given that search engines are more likely to point you in the direction of Taipei than anywhere else in Taiwan.

One thing that might change all of that, though, has been the long-awaited reopening of the Alishan Forest Railway (阿里山森林鐵路) after considerable damage caused by typhoons and earthquakes, which shut the railway down for more than a decade. With the branch railway operational again, the area is receiving a massive increase in tourism, with people traveling to Chiayi just to take the iconic railway.

As I move on below, I’ll introduce the history of Beimen Station, including some additional information about the Alishan Railway, with a timeline of events, an introduction to the station’s architectural design, and I’ll end by offering readers an idea about how to visit.

Hokumon Station (北門驛 / ほくもんえき)

To introduce the history of the Beimen Railway Station, I’ll have to start by offering a bit of a backstory of events leading up to the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan, and the development of the railway, which ushered in an era of modernity, development, and economic opportunity.

Overall, the construction of Taiwan’s railway not only offered the people of the island with a means of public transportation, but allowed for the transport of goods and services around the island. This ushered in a period of connectivity and economic opportunity that the people of Taiwan had yet to experience. While there were obvious benefits for the residents of the island, it’s also important to keep in mind that the railroad was an instrumental tool, which assisted in fueling Japan’s goal of extracting the island’s precious natural resources.

The history of the railway in Taiwan dates back as early as 1891 (光緒17年), just a few short years prior to the Japanese take over of the island. The original railway project, ironically, turned out to be one of the most ambitious development projects undertaken by the Qing government, under the leadership of then governor, Liu Mingchuan (劉銘傳). The Qing-era railway would stretch from the port city of Keelung (基隆) to Hsinchu (新竹), but even though the project was led by foreign engineers, the final result turned out to be quite rudimentary, and ultimately came at far too high of a cost for the Qing to finance beyond the northern portion of the island.

One could argue that they were preoccupied with both war and revolution, so finances were stretched quite thin, but it’s also important to note that the Qing never particularly cared very much about developing Taiwan, nor did they have the ability to control anything beyond a few pockets of communities along the western coast.

Understandably, if you don’t care about something, why waste money on it?

The Qing Dynasty was established at a time when China’s previous rulers had become far too weak to contend with the constant rebellions and civil disorder that were erupting around the country, and in what may seem like a case of history repeating itself, by the late 1800s, Qing rule had similarly become incompetent, and corruption was rife throughout the country.

The corruption and incompetence that was prevalent throughout China’s bureaucracy prevented its rulers from modernizing its military, but it also resulted in some diplomatic missteps that ultimately led to war with Japan. Having recently gone through a revolution of its own, in a very short time, Japan had transformed itself into one of the world’s major military powers, and when the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) broke out, it ended about as quickly as it began. China’s surrender resulted in considerable embarrassment for the Qing rulers, who were entirely unprepared to wage a modern war against a much better equipped Japanese military. But more importantly, for the first time in recorded history, the balance of power in Asia shifted away from China.

In response, the Qing’s surrender to the Japanese would ultimately become the catalyst for revolution, which would within a little over a decade would bring thousands of years of imperial rule to an end.

Unable to compete with might of the Japanese military, the Qing elected to sue for peace, just a little more than six months into the war, which formally came to an end with the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki (下関条約).

Most notably, the key stipulations of the treaty were that China would be forced to recognize the independence of Korea, which had until that point been a vassal kingdom that had to pay tribute to China, and that Taiwan and the Penghu Islands would be ceded to Japan.

Shortly thereafter, the Japanese military set sail for Taiwan, landing in Keelung on May 29th, 1895. When they arrived, they were met with resistance from the remnants of the Qing forces stationed on the island, local Hakka militias, as well as from indigenous groups. Over the next five months, the Japanese made their way across the island waging a brutal guerrilla war that ‘officially’ came to an end with the fall of Tainan. That being said, even though the military had more or less taken control of Taiwan’s major towns, the insurgency against their rule lasted for quite a few more years, resulting in some terrible massacres.

Similar to what took place in China, the superiority of the modern Japanese military easily dispatched the local militias that put up a resistance. The campaign, however taught the Japanese a hard, yet valuable lesson, as figures show that over ninety-percent of the Japanese military deaths during the pacification of Taiwan were mostly due to malaria-related complications.

Link: Disease and Mortality in the History of Taiwan (Ts'ui-jung Liu and Shi-yung Liu)

History has shown that for the majority of time that the Qing controlled Taiwan, they were mostly uninterested in the island referring to it condescendingly as a "ball of mud beyond the sea" which added "nothing to the breadth of China" (海外泥丸,不足為中國加廣). The hostile environment on the island was just one of the many reasons why they were so ambivalent about doing much during their time here, but that probably wasn’t something they were too forthcoming with when the Japanese took an active interest in taking over.

Having to learn the hard way, the Japanese authorities were intent on addressing these health-related issues, especially since it stood in their way of extracting the island’s vast treasure trove of natural resources. To accomplish that mission, they would first have to put in place the necessary infrastructure for combating these diseases.

It would end up taking several years for the Japanese to take complete control of Taiwan, and yes, their losses were considerable, however, it was the people of Taiwan suffered the most, especially with the heavy-handed tactics that the colonial government took to suppressing dissent to their rule. That being said, when the dust of war settled, and the island started to develop, living standards improved, and the frequency of rebellions decreased. As mentioned earlier, in 1906, when the Meishan Earthquake (梅山地震), the third deadliest earthquake in Taiwan’s recorded history, reduced Kagi to rubble, the military and medical personnel were quickly dispatched to assist in rescue and recovery efforts. The earthquake may have devastated the city, but despite all the suffering and destruction it caused, it also brought with it opportunity. The reconstruction of Kagi allowed the government to completely alter the town’s urban planning structure, and developed it at such a rapid pace, that the town started to flourish as it never had before. As a major economic center for agriculture, timber and sugar, and Taiwan’s fourth-most populated city at the time, the colonial government placed a considerable amount of attention on the urban development of the city, and the response of the Japanese authorities to the earthquake in regard to both their humanitarian efforts and the reconstruction of the town was something that brought people together in a way that, after a decade of violence, many people would have imagined unlikely.

One of the colonial government’s first major development projects in Taiwan got its start shortly after the Japanese stepped foot in Keelung in 1895. The military had brought with them a group of western-educated military engineers, who were tasked with getting the existing railway between Keelung and Hsinchu back up and running. They were also tasked with coming up with proposals for the extension of the railway across the island. As the military made its way south, the engineers followed close behind surveying the land for the future railway. By 1902, the team came up with a proposal for the ‘Jukan Tetsudo Project’ (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), otherwise known as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project,’ which would have the railroad pass through each of Taiwan’s established settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄).

Construction was divided into three phases with teams of engineers spread out between the ‘northern’, ‘central’ and ‘southern' regions of the island. Amazingly, in just four short years, from 1900 and 1904, the northern and southern portions of the railway were completed, but due to unforeseen complications, the central portion met with delays and construction issues. Nevertheless, the more than four-hundred kilometer western railway was completed in 1908 (明治41), taking under a decade to complete, a feat in its own right, given all of the obstacles that had to be overcome.

To celebrate this massive accomplishment, the Colonial Government held an inauguration ceremony within the newly established Taichung Park (台中公園) with Prince Kanin Kotohito (閑院宮載仁親王) invited to take part in the ceremony. For its part, the colonial government touted the completion of the railway as a major accomplishment that would usher in a new era of peace and stability in Taiwan, and one that would help to both bring about a period of modernization and economic stability.

For the most part, they were right about that. Taiwan’s railway has been transformational, and even today, it is instrumental in maintaining a high quality of life in the country.

As mentioned earlier, the northern and southern portions of the railway were completed the fastest. The southern section, originally between Kaohsiung and Tainan opened for service in 1900, and just two years later, the railway was extended to Chiayi, where the First Generation Kagi Station (嘉義驛) opened on April 20th, 1902 (明治35年). The opening of this particular station was monumental not only in that it connected one of southern Taiwan’s largest towns, but also for the colonial government’s plans to start extracting natural resources from the nearby mountainous region.

Prior to the completion of the main line, construction on the Alishan branch railway commenced in 1907, with a terminus for the branch line at Kagi Station. The construction of the railway, however, which is now considered to be one of the ‘most beautiful rail lines in the world,’ met with considerable difficulties and delays.

Just after taking control of Taiwan, the colonial government dispatched researchers across the island to identify areas that were ripe for the extraction of natural resources, and in 1899, massive reserves of cedar were discovered in the Alishan region. Planning for the construction of a branch railway, which would assist in the transportation of timber from the mountain got underway shortly thereafter. However, the planning process, which included surveying the land, and mapping out possible routes, ended up taking several years.

During the planning process, one of the main concerns was the slope of the ascent up the mountain, and ultimately the cost of undertaking such an ambitious endeavor. However, when plans were finalized and sent back to Japan for review, the project had to be shelved due to the Japanese-Russian War between 1904 and 1905. When the war came to an end, and the finances were available, construction on the railway officially started in 1907, just a year after the earthquake toppled much of what once stood in Kagi. Interestingly, though, instead of directly funding the project, the Japanese Diet signed a contract with a private company, Fujita-Gumi (藤田組), which would be responsible for the construction of the railway, and later, the extraction of timber. That being said, after investing a considerable amount of funds in the construction of the railway, the company discovered that in order to complete the project, they’d ultimately have to invest more than double what they had already committed, which gave them cold feet and construction came to an abrupt halt just over a year in with the railway half completed.

By 1910, the Japanese government, victorious in their war with the Russians, and having already started reaping tremendous wealth from their Taiwanese colony, bought out the Fujita group and construction on the railway started once again. The 86 kilometer branch railway was completed in 1913, a massive achievement at the time, as it was the highest-elevated railway in the Japanese empire, and required a tremendous amount of engineering know-how.

Along the route, trains traveled through more than fifty tunnels and over (almost) eighty wooden bridges, starting from an elevation of 30m to 2,216m at its terminus. To compliment the line, twenty-two stations were constructed, one of them being Hokumon Station (北門驛 / ほくもんえき), a short distance from Kagi Station.

Despite being quite small, Hokumon Station would become one of the most important stations along the route due to its being situated in a strategic location next to the headquarters of the Forestry Bureau, a village set up for the workers (known today as Hinoki Village), the lumber mills, a timber factory, and the Machine Works (林鐵修築工程), which was responsible for the maintenance of the trains and the railway.

The station officially opened for service on October 1st, 1910 (明治43年), and if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll likely notice that this was a few years prior to the completion of the railway. During the construction process, Hokumon Station was instrumental in running limited service between Kagi Station (嘉義驛) and Taketozaki Station (竹頭崎驛), serving as the main way-point for transporting construction staff to sites along the railway.

I probably sound a bit old saying this, but a lot of people may find it hard to believe, but before the advent of the Internet and Social Media, word also tended to spread quickly, and soon after the Alishan railway was completed, people from all over Taiwan started discovering that Alishan was spectacularly beautiful, quickly transforming it into a popular tourist destination. In 1918 (大正7年), passenger service was added to the railway for the first time, transporting tourists up into the mountains on what were known as ‘convenience cars’ (便乘列車), which were added to the rear of the freight trains.

As time went by, the Alishan Line continued to grow, and more stations were eventually added, with the line extended even higher into the mountains. By 1933 (昭和8年), the same year that the Second Generation Kagi Station (第二代嘉義車站) was completed, Sakaecho Station (栄町驛 / さかえちょうえき), located in the space between Kagi and Hokumon Station was constructed, and even more importantly, Niitakaguchi Station (新高口驛) opened to massive approval from the tourist public.

Personally, I’m not particularly sure why Sakaecho Station was ever constructed, but Niitaguchi Station on the other hand ended up being the station the highest station in the Japanese empire. It was also the gateway to ‘Mount Niitaka’ (新高山), which we refer to today as Yushan, or Jade Mountain (玉山) and offered an express route to the lodge near the trailhead. When it opened, hikers were able to summit the mountain much more quickly, making it accessible for anyone who wanted to climb Taiwan’s (and Japan’s at the time) highest peak.

When the Japanese were forced to give up control of Taiwan at the end of the Second World War, the extraction of cypress from the mountains in the Alishan area is something that actively continued under the new regime, and the branch railway remained active for quite some time. The popularity of the railway with all of Taiwan’s new arrivals, though, made Hokumon Station, which had started being referred to in Mandarin as ‘Beimen Station’ a bit outdated, so, in 1973 (明國62年), a new passenger station was constructed on the opposite side of the tracks, leaving the original station responsible for managing the freight that was passing through.

The popularity of the railway would eventually fall into decline after the completion of the Alishan Highway (阿里山公路), allowing people to drive their own vehicles up the mountains, or take buses. With the ability to travel up the mountain at your leisure, the railway would became a nostalgic tourist attraction, but due to a number of accidents along the route over the following decades, in addition to damage caused by landslides, the railway was shut down for almost a decade for repairs.

Sadly, in 1998, just a month after Beimen Station was officially recognized as a Chiayi City Protected Heritage Site (嘉義市定古蹟), fire broke out at the station, causing irreparable damage to about forty percent of the building. The city government promptly approved funding for repairs, and construction quickly got underway to restore the building, simultaneously taking the initiative to completely clean up the station-front, making it more pedestrian-friendly.

What happened after that, I’ll quickly touch upon, but since there are some legal matters that are still going through the court system, I’m not going to say too much. To briefly summarize, the ‘Beimen Passenger Station’ on the opposite side of the tracks was phased out in 2007, with the building quickly torn down so that it could be replaced. Passenger service was returned to the original station for a short time while a new building was being constructed.

The new station would be considerably larger, and would even include a hotel (阿里山麗星北門大飯店). The Chiayi City government entered into a BOT agreement with a private company, resulting in years of litigation and appeals on both sides. The issue at hand was that with the railway shutdown due to considerable damage caused by typhoons, the company took a major loss of revenue, given that few were interested in staying a hotel that connected to a shut down railway. The Chiayi City Government can’t really be blamed for any of this, though.

Link: The role of Public-Private Partnerships in Conserving Historic Buildings in Taiwan

Today, with the railway back up and running, both the new passenger station and the hotel are open to the public. With freight service phased out, and passenger services transferred across the tracks, the historic station has been emptied and once again entered a period of restoration, and unfortunately, during my two recent trips to the city, the interior of the building was inaccessible as construction had yet to be completed.

At some point in the near future the station will be completely reopened to the public as a tourist destination now that its time as a railway station has officially come to an end. However, I’m sure with the eventual retirement of Chiayi Station, and the inclusion of the Alishan Forest Railway Garage Park (阿里山森林鐵路車庫園區), Beimen Station will become part of a greater railway park that celebrates the city’s rich history.

Before I move on to detailing the architectural design of the station, I’ve put together a condensed timeline of events in the drop down box below with regard to the station’s history for anyone who is interested:

-

1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese take control of Taiwan as per the terms of China’s surrender in the Sino-Japanese War.

1896 (明治29年) - The Colonial Government puts a team of engineers in place to plan for a railway network on the newly acquired island.

1899 (明治30年) - The Japanese discover massive reserves of precious cedar in the Alishan Forest Area and planning starts for a railway for the extraction of timber.

1900 (明治33年) - The first completed section of the Japanese-era railway opens for service in southern Taiwan between the port town of Kaohsiung and Tainan. The transportation bureau sends engineers to the Alishan area to investigate the feasibility of building a railway to transport timber freight down the mountain.

1902 (明治35年) - After years of planning and surveying, the government formally approves the Jukan Tetsudo Project (縱貫鐵道 / ゅうかんてつどう), a plan that will connect the western and eastern coasts of the island by rail.

1902 (明治35年4月20日) - The First Generation Kagi Station opens for service along the southern portion of the railway.

1903 - 1904 (明治36-37年) - Planning for the forest railway enters a several year period of surveying the land and possible routes for the railway with the slope of the ascent up the mountain being one of the main concerns. However, when plans for the route were finalized and sent back to Japan for review, the project was shelved because of a lack of funds due to the Japanese-Russian War.

1906 (明治39年) - On March 17th, the Great Kagi Earthquake (嘉義大地震), with an epicenter in Meishan (梅山) leveled much of what had been constructed in the area. Later that year, the Japanese Diet officially approves a development project by the Fujita-Gumi (藤田組) conglomerate, which obtained the licensing rights for the railway, which revived the project.

1907 (明治40年) - Construction of the Alishan Railway (阿里山林鐵) commences with the project split into three phases. However, with construction already well underway, the group discovered that in order to complete the project, an additional 1.5 million yen (on top of the the 1.3 million already spent) would have to be spent to complete the railway.

1908/2/11 (明治41年) - The Fujita-Gumi group officially announces the suspension of the half-completed Alishan railway construction project due to a lack of financial resources.

1908/10/24 (明治41年) - The 400 kilometer Taiwan Western Line (西部幹線) is completed with a ceremony held within Taichung Park (台中公園) on October 24th. For the first time, the major settlements along the western coast of the island are connected by rail from Kirin (Keelung 基隆) to Takao (Kaohsiung 高雄).

1910 (明治43年) - Forestry officials propose restarting construction on the railway with a plan proposed to have the Japanese government buy out the Fujita group. The proposal was approved within two months and construction started right away.

1910/10/1 (明治43年) - The portion of the railway between Kagi Station (嘉義驛) and Taketozaki Station (竹頭崎驛) opens for limited service. During this period of limited service, Hokumon Station is completed, and likewise opens for freight traffic, and serves as the main way point for transporting workers to the construction sites along the railway.

1913 (大正2年) - The nearly ninety kilometer Alishan Forest Railway (阿里山線) between Kagi Station and Shohei Station (沼平驛 / しょうへいえき) is fully completed and opens for service.

1918 (大正7年) - For the convenience of local residents, hikers and tourists, passenger cars (便乘列車) are added to the rear of the freight trains that make their way up the mountain.

1933 (昭和8年) - The Second Generation Kagi Station, designed by Ujiki Takeo (宇敷 赳夫/うじき たけお) opens for service. That same year, Sakaecho Station (栄町驛 / さかえちょうえき), located between Kagi Station and Hokumon Station opens for service.

1933 (昭和8年) - The Alishan Railway becomes a major tourist attraction when the railway is extended to Niitakaguchi (新高口驛) from Shohei Station (沼平驛), offering an express route to the trailhead of Mount Niitaka (新高山), what we know today as Yushan (玉山).

1945 (昭和20年) - The Second World War comes to an end and the Japanese surrender control of Taiwan to the Chinese Nationalists.

1973 (明國62年) - A new ‘Beimen Station’ (新北門車站) is constructed, leaving the original station in charge of freight services from the mountain as well as maintenance services.

1982 (民國71年) - With the completion of the Alishan Highway, the number of passengers on the train to Alishan starts to decline.

1998 (民國87年) - An eventful year for the station, in April it is recognized as a Chiayi City Protected Heritage Site (嘉義市定古蹟), but then a month later fire breaks out, destroying at least half of the historic building. A few months later, funding is approved for its restoration.

2001 (民國90年) - The square in front of the station undergoes a period of restoration and improvement, making the area entirely pedestrian.

2007 (民國96年) - The last train departed from the ‘new’ Beimen Station, and passenger services were moved back to the original station.

2008 (民國97年) - The ‘new’ station is torn down and a much larger ‘newer’ Beimen Station is constructed in its place. This time, the new station includes a hotel (阿里山麗星北門大飯店) and a BOT agreement with a private company, which eventually results in years of litigation between the private company and the city.

2009 (民國98年) - Due to the devastation caused by Typhoon Morakot, services along the railway were limited for several years, which meant that Beimen Station, the newly constructed hotel, and the area around the station suffered economically.

2023 (民國112年) - Beimen Station enters a period of restoration and operation of the railway is transferred again to the ‘new’ station on the opposite side of the railway.

Architectural Design

If you took the time to read the long-winded introduction to the history of Beimen Station, you’re probably already aware that the building has gone through considerable change over the century that it has been in operation. The fire that devastated parts of the building, for example, not only altered the function of the station, but its interior layout as well. Fortunately, the building was put back together, and put back to work in no time.

The current restoration of the building, though, I have to say seems to have changed things quite a bit, and although I’m writing this article before the project has been completed, from what I’ve seen from both the exterior, and peering through the windows, I’m not particularly a big fan of what that has been done.

To start, I suppose it’s probably easiest to just explain that Beimen Station, like many of its contemporaries in the early 1900s, was constructed with Taiwanese Red Cypress (臺灣紅檜) in a traditional architectural style that became common not only in Taiwan, but back in Japan as well.

One thing that the Japanese discovered the hard way in their early years of developing Taiwan was that their traditional methods of construction, primarily making use of timber, was something that wasn’t ideal in the long-term in this environment. Not only was Taiwan prone to earthquakes and typhoons, but it was also home to a powerful little pest, known as the white termite (白蟻), which took pleasure feasting upon all of the buildings that were being constructed around the island. Fortunately, by the time Beimen Station was constructed in 1912, the Japanese had already become frustrated feeding Taiwan’s termites, and had come up with methods to continue using cypress for the construction of buildings, while also preventing termites from doing their thing.

The station was constructed with a rectangular-shaped core, with a length of 22 meters and a width of 11 meters, on an elevated cement base that prevented the termites from getting to the wooden sections of the building. The rectangular shape of the building was probably one of the more common characteristics for these early stations as the design allowed for an even partition of the passenger and staff sections of the station. Where Beimen Station differs from most of its contemporaries, though, is that the staff-side was considerably larger than the passenger side. The reason for this was simply because the station’s primary responsibility was never really intended to serve large crowds of tourists, but instead to deal with all of the freight that was being transferred to the lumber yards nearby.

If you’re looking at the station in person, and keeping in mind the official measurements above, you’ll probably find it a bit odd that the station is measured at 11 meters deep. What the literature doesn’t actually tell you very clearly is that the depth also includes the platform space for the station, which extends beyond the station house. Unfortunately, as I mentioned above, the interior of the station is still in the process of being restored, so until it completely reopens, I won’t be able to provide photos of what you’ll find inside. From the information provided, though, the interior is constructed entirely with cypress and features bamboo and mud insulated walls (編竹夾泥牆), with all four sides of the building featuring large Japanese-style paneled sliding glass windows (日式橫拉窗).

With regard to the passenger area of the station, there was a small waiting room (等候室), a square (廣場) in front of the station, the porch (門廊), platform space (月台), and the ticket booth (檢票口). Within the staff section, there was an office (辦公室), the ticket booth (售票口), baggage check-in office (行李托運處), and a signal room (信號室). Additionally, there was a detached warehouse outside of the station that included duty rooms (值班室) and a tea space (茶水間).

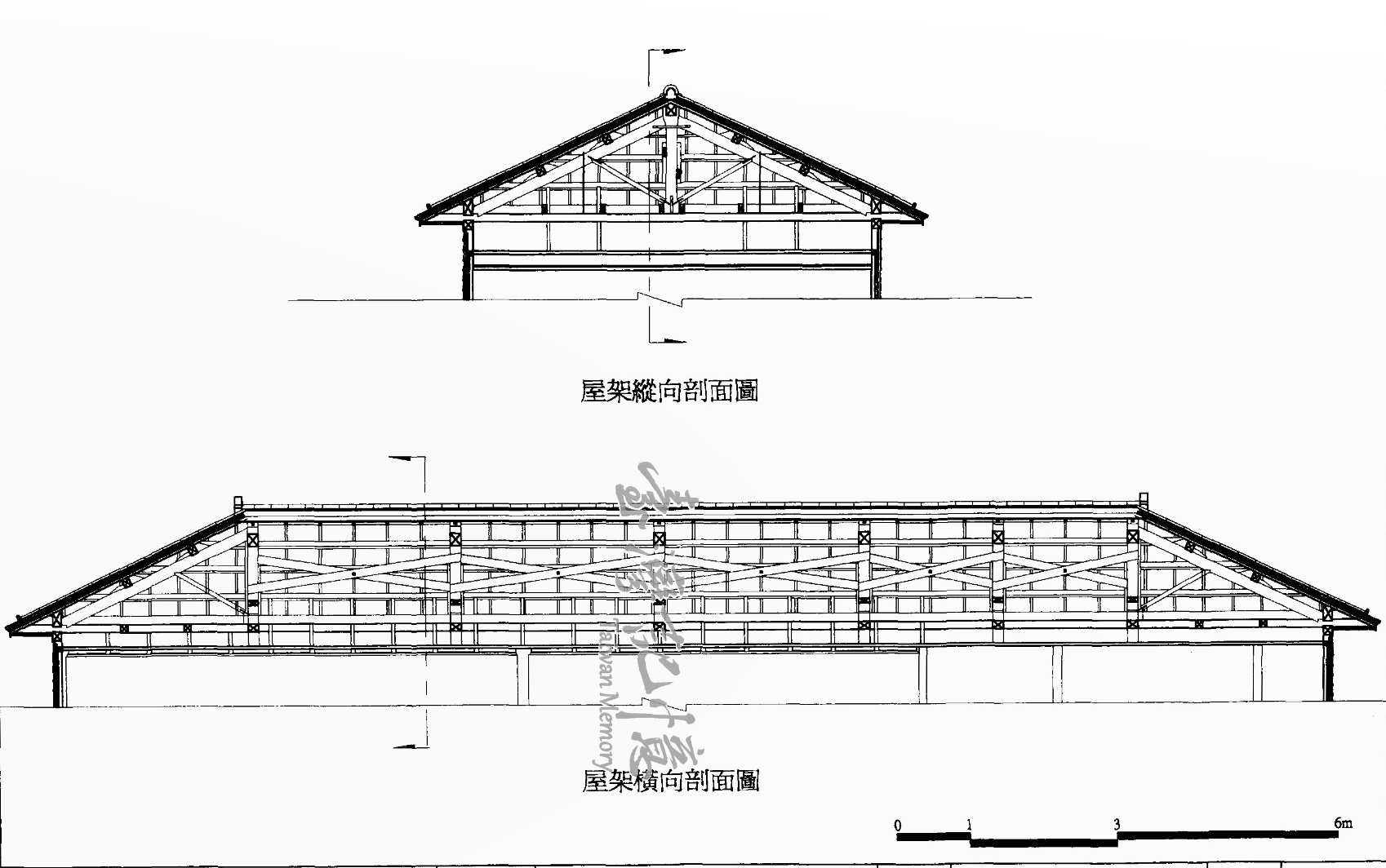

If I were to just tell you that the building was constructed in a ‘rectangular-shape’, I wouldn’t be doing it justice, so let me explain some of the more advanced architectural terms. First, instead of referring to it as ‘rectangular’, it’s important to note that the building was constructed using the traditional irimoya (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of design. An ubiquitous style of Japanese architectural design, ‘irimoya’ is most often referred to in English as the “East Asian hip-and-gable roof,” which is something that I don’t particularly think really helps the average English-language reader really understand what’s actually going on.

To explain, the key thing to keep in mind about irimoya-style buildings is that they feature what’s known as a ‘moya’ (母屋 / もや), which in this case is essentially just the rectangular core of the building. But then again, almost every type of building around the world features a base that is directly beneath the roof, so what you’ll want to keep in mind in this regard is that Japanese architects have come up with a genius network of pillars and trusses within the ‘moya’ that not only ensure the building’s stability, but also adds an ample amount of support for the weight of the roof. What ends up completing this style of design is that the core of the building is (almost) always complimented by a roof that eclipses the size of the core. While its true that a lot of emphasis is placed on decorative roof designs within Japanese architectural design, none of it would be possible without the mathematical and carpentry genius it takes to construct the base, which is why I think the roof shouldn’t always be the main focus.

Given that the term in English is translated as the “East Asian hip-and-gable roof,” you might understand why I take issue with the term given that Beimen Station’s roof was constructed using the traditional yosemune (寄棟造 / よせむねづくり) style of design. In most cases, ‘yosemune-style’ roofs are combined with another style of roof design to make the geometrically-shaped ‘hip-and-gable’ roof. However, Beimen Station’s ‘yosemune’ roof is essentially just a four-sided ‘hip’ roof that covers and extends beyond the base of the building. Thus, the so-called ‘hip-and-gable’ roof doesn’t actually feature a ‘gable’ section, making it quite simple as far as these things go.

The upper part of the roof is covered with Japanese-style black tiles (日式黑瓦) while the lower eaves are covered with rain-boards (雨淋板) that extend beyond the roof and help to direct the flow of rain water on rainy days, while also offering passengers some extra protection from the elements. The tiles that cover the roof have faded in color, so it’s difficult to tell how old they are, although it’s highly likely that they were replaced after the restoration to the building in 1998.

The rain-boards that extend from the roof are supported by a network of pillars on the sides and the rear of the building where they extend much further from the roof than they do at the front. Even though the roof is somewhat basic in terms of its decorative elements, especially when compared to the hip-and-gable style roofs you’ll find on other Japanese-era buildings, there are still a number of elements to take note of with the various types of tiles that connect to cover the roof.

Nokigawara (軒瓦/のきがわら) - The roof tiles placed along the eaves lines.

Noshigawara (熨斗瓦/のしがわら) - Thick rectangular tiles located under ridge tiles.

Munagawara (棟瓦 /むねがわら) - Ridge tiles used to cover the apex of the roof.

Onigawara (鬼瓦/おにがわら) - Decorative roof tiles found at the ends of a main ridge.

While not exactly part of the roof, one thing that adds a bit of shape to the building is the addition of a roof-covered ‘kurumayose' (車寄/くるまよせ) porch, which protrudes from the rain-boards on the flat front of the building with a pair of pillars holding it up. The roof of the porch features a two-sided, almost triangular-like, kirizuma-style roof (切妻造 / きりづまづくり) facing in the opposite direction of the roof above, adding to the three dimensional design of the building. Even though the ‘porch’ is decorative in nature, it’s also functional in that it allows passengers coming to the station to know which is the entrance to the station that they’re supposed to use, rather than attempting to enter the staff-side of the station.

In the near future, I hope to visit the station again when the restoration has been fully completed so that I can include photos of the interior, and better explain what you’ll find inside. During my most recent visit, I was able to peer in through the windows at the mostly empty building, so I could see that the original wooden benches and the ticket booth and window were still there, which is great. On my next visit, I’d also like to spend more time exploring the railway park nearby. Until then, I hope this introduction helps you understand the station a little more.

Getting There

Address: #428 Gonghe Road, East District, Chiayi City

(嘉義市東區共和路428號)

GPS: 23.487778, 120.455278

Whenever I write about one of Taiwan’s historic train stations, it probably makes sense that the best possible advice for getting there is to simply take the train. In this case, though, unless you find yourself taking the Alishan Forest Railway, you’re not likely to find yourself on a train that stops at the (current) Beimen Station.

Chiayi is a pretty popular place these days, though, and there are a number of methods for travelers to reach the city, without taking the train. The historic Beimen Station is a short walk from Chiayi Station, and even closer to the famed Hinoki Village, both of which offer options for public transport, so if you’re in the city, you shouldn’t have too much trouble getting yourself to this historic little station.

If, however, you are making use of the railway as your primary method of transportation, arriving in Chiayi is pretty simple. It doesn’t matter whether you’re traveling southbound, or northbound, as one of Taiwan’s major railway stations, Chiayi Station is accessible via all of the western trunk line’s express train services as well as the local commuter trains, so matter what train you get on, it’ll make a stop at Chiayi station.

High Speed Rail / Bus Rapid Transport

If you arrive in town via Taiwan’s High Speed Rail, you’ll probably notice that the station is located a fair distance away from the downtown core of the city. Taking the HSR to Chiayi saves a lot of travel time, especially if you’re traveling from Taipei, but once you’ve arrived, you’re going to have to either take a taxi or a bus into town. Fortunately, Chiayi Station is connected to the Chiayi High Speed Railway Station (嘉義高鐵站) through the Chiayi Bus Rapid Transit (嘉義公車捷運), an express bus service that connects the High Speed Rail station to the city.

If you arrive in the area via High Speed Rail, you can easily exit the station to the bus parking area and hop on either bus #7211 or #7212 to get yourself to the downtown core of the city.

Link: Bus #7211 and #7212 schedule (Chiayi City Bureau of Transport)

Even more convenient is that Bus #7212 stops directly at the Chiayi City Cultural Center Bus Stop, which I’ll mention below.

Bus

As I just mentioned, in recent years, Chiayi City has upgraded its bus network into a “BRT” (Bus Rapid Transport) system similar to the one in used in Taichung. The new system has replaced all of the old Chiayi Bus (嘉義公車) routes that used to exist. So, if you’ve looked at other resources online that haven’t been updated, you might find yourself a bit confused about how to get around.

If you want to make use of Chiayi City’s public bus routes, there are numerous options for getting to Beimen Station, but the important thing to keep in mind is that the station is accessible via two different stops, both of which are quite convenient for travelers. Below, I’ll separate the route options based on the stop where you’ll get off and provide links to their schedules. However, it’s important to keep in mind that links like this in Taiwan are incredibly unreliable. If you discover that one of the links isn’t active, let me know in the comments below and I’ll update it!

Hinoki Village bus stop (檜意森活村)

From the Hinoki Village Bus Stop, you’ll simply cross Linsen East Road (林森東路) and walk down the narrow Gonghe Road (共和路) for about a minute or two before you arrive at Beimen Station.

Bus Routes: Yellow Line, Yellow Line A, Lohas Line 1, Lohas Line 9

Chiayi City Cultural Center bus stop (文化中心)

From the Chiayi Cultural Center Bus Stop, you’ll simply cross Zhongxiao Road (忠孝路) by the train tracks and walk down Lane 243 of Gonghe Road (共和路243巷) for about a minute or two before you arrive at the station.

Bus Routes: Red Line, Red Line A, #7202, #7203, #7204, #7217, #7304, #7305, #7309, #7315, #7316, #7700, #7701

Youbike

Finally, Chiayi is very well-equipped with Youbike Stations scattered across the city in convenient tourist-friendly locations. If you’ve arrived in town via the train, there is a large Youbike station just outside where you’ll be able to swipe your EasyCard and go for a ride on one of the shared bicycles.

If you’re riding a Youbike, you can easily dock the bicycle at the docking station next to Hinoki Village (檜意森活村), and check out the station, which is across the street.

The roads in Chiayi are quite wide, and drivers are a lot more considerable towards pedestrians than they are in other areas of Taiwan, so if you’re in the area, making use of the YouBike service is a highly recommended option. They also allow you to stop and check out any of the cool things you’ll see while riding around the streets and the historic alleys of the city.

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend downloading the Youbike App to your phone so that you’ll have a better idea of the location where you’ll be able to find the closest docking station.

Now that the historic Beimen Station has (once again) been phased out and replaced by a modern station on the opposite side of the tracks, the little wooden station house has entered a new period in its existence as a tourist attraction. Having recently been restored, the station should soon be opened to the public, likely as an extension of the nearby Hinoki Village, where you’ll be able to learn about the history of the Alishan Forest Railway and the station itself. That being said, until the station fully reopens to the public, its unclear what purpose it will actually serve.

As a protected heritage property, and an important part of Chiayi’s history, it’s great that the station has been restored and will soon become another one of the city’s tourist destinations, but I do have to say that some of the decisions made with regard to its restoration were somewhat questionable. Hopefully, though, when the interior of the station opens to the public, and we get to enjoy the finished product, some of those issues will be cleared up. If you’re in the area visiting Hinoki Village, I highly recommend crossing the street and checking out this beautiful little train station.

References

Beimen railway station | 北門車站 中文 | 北門駅 日文 (Wiki)

Alishan Forest Railway | 阿里山林業鐵路 中文 | 阿里山森林鉄路 日文 (Wiki)

Chiayi railway station | 嘉義車站 中文 | 嘉義駅 日文 (Wiki)

Tainan Prefecture | 臺南州 中文|台南州 日文 (Wiki)

嘉義市市定古蹟阿里山鐵路北門驛調查研究規劃 (嘉義市政府)

阿里山林業暨鐵道文化景觀 (國家文化資產網)

林業鐵路歷史介紹 (林業鐵道)

北門驛現址─北門車站 (國家文化記憶庫)

[嘉義市].檜意森活村.阿里山森林鐵路車庫園區.北門驛 (Tony Huang)