The historic residence of one of Taiwan’s leading modern literary figures, Wu Zhuo-Liu (吳濁流) recently opened to the public after the Hsinchu government both restored and renovated the traditional Hakka-style home into a memorial museum for the iconic author.

The house which is located in Hsinchu’s Hsinpu township (新埔鎮) offers visitors a glimpse into the life of the man who authored several influential novels and helped to shape the notion of a distinct identity for the people of Formosa that wasn’t “Chinese” or “Japanese” but solely Taiwanese.

Before we start, I'm going to be honest - I had no idea that this house was the home of someone as historically significant as Wu Zhuo-Liu nor did I even know who he was - I just passed by and saw the words "Memorial Hall" (紀念堂) next to a beautiful old home and decided to check it out.

Later, when I started to do research for this blog however I quickly found out that I was walking around the home of a giant of modern Taiwanese history and a person who I was absolutely sure that I would like.

Mr. Wu was not only an advocate of a separate Taiwanese identity but described for the world the history and harsh reality that the people of Taiwan have had to face for the past several centuries.

After learning a bit about the man and his life, I knew that his books had to be added to my collection and I went out right away and bought an English version of his "Orphan of Asia" (currently reading) and a Chinese version of "Fig Tree" (無花果).

I'm only halfway through the first book, but I can tell you that I'm extremely happy that in my ignorance I happened upon this Memorial Home as it helped me learn more about the struggle the Taiwanese people have endured for hundreds of years up until today.

Wu Zhuo-Liu (吳濁流)

Wu Zhuo-Liu (吳濁流) was born as Wu Jintian (吳建田) in 1900 just a few short years after the Japanese Colonial Era began. Mr. Wu, a Hakka from Hsinchu’s Hsinpu Village grew up in Japanese occupied Taiwan and despite hailing from a family of farmers, received a formal education in the Japanese Education system.

As an educated man Wu spent much of the first part of his life teaching in the Primary School system. At the age of 41 he quit his highly respected job as a teacher and took a job as a reporter in China where he spent fifteen months in Nanjing (At that time the capital of China) writing about the war that had enveloped the nation.

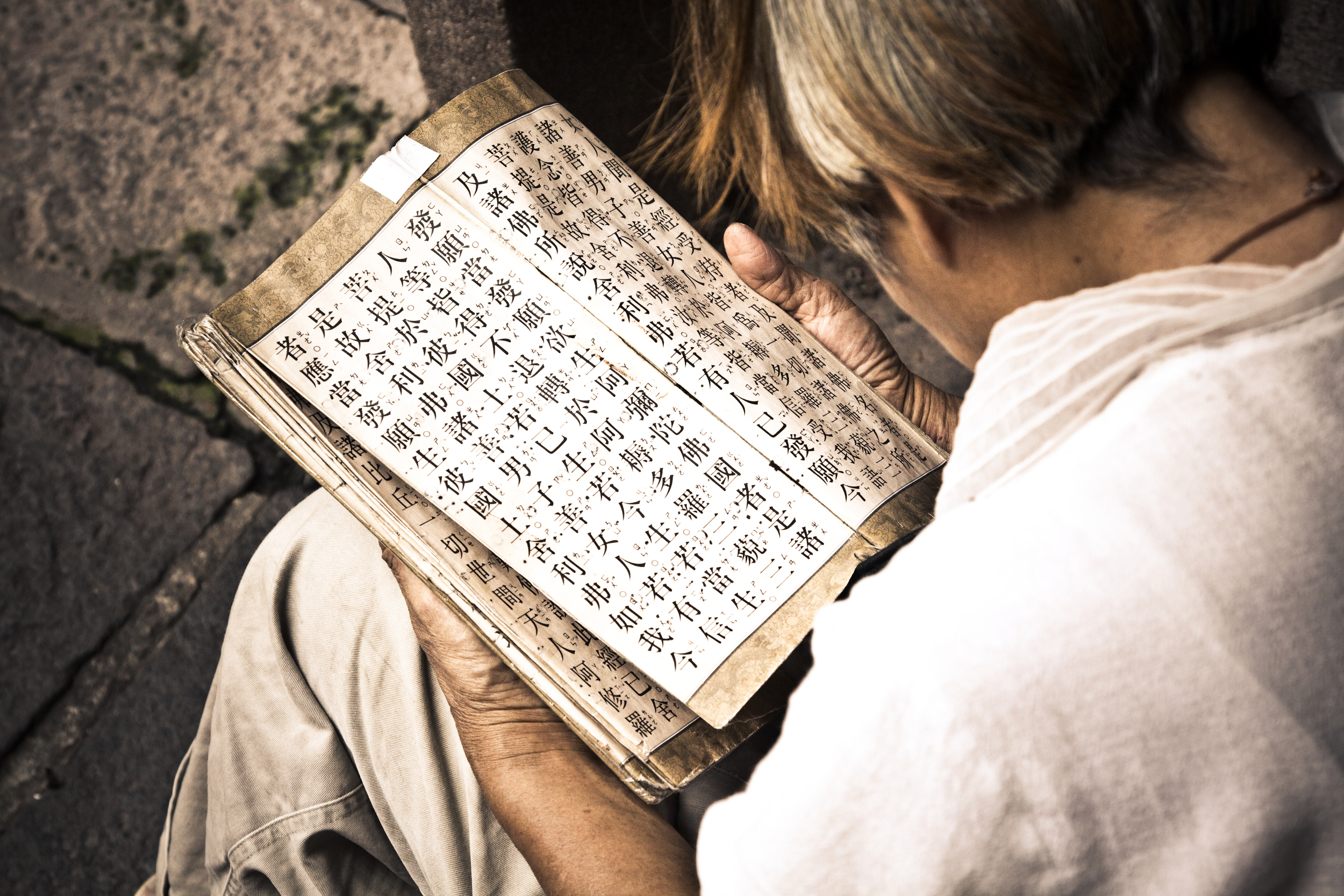

When Wu returned to Taiwan in 1943 he continued working as a journalist and also started to write novels and short stories based on his, and the experiences of his fellow Taiwanese people. In 1945 he penned what would become his most famous work titled the “Orphan of Asia” (亞細亞的孤兒) which highlighted the ambiguity felt in the hearts of Taiwanese as to their conflicting sense of identity and is a book that even today people can still relate to.

In 1968, Wu published his memoirs, an autobiographical look at life during the Japanese Colonial Era and then the Republic of China era. The book continued with the themes of his growing political conscious and search for identity. Both realistic and politically charged, its description of the events of the 228 Massacre and the repressive nature of the Chinese Nationalists who controlled Taiwan with an iron fist were enough to earn it a swift ban by the authorities due to the fact that discussing such things was taboo at the time.

Unfortunately Wu died in 1976 and at the age of 76 and was ultimately unable to see the lifting of Martial Law or the end of the repressive White Terror period which he had endured for much of his life. His contribution and his courage however are widely respected today in Taiwan and his books are a constant reminder of the tension the Taiwanese people have had to endure over the last century with regard to who they really are.

History and Design

Thanks to the efforts of the Hsinchu City Bureau of Cultural Affairs (新竹市文化局), the Wu Zhuo-Liu Memorial House (吳濁流故居) recently re-opened to the public after several years of renovation and restoration.

This memorial house is but one of the historic homes of Hsinpu village that has been restored (or is in the process of being restored) and opened to the public over recent years. Hsinpu Village has become an extremely important place for the Hakka people of Taiwan thanks to its wealth of cultural history and more importantly due to the fact that Yimin Temple (義民廟), the Mecca for the Hakka people is situated within the village.

In conjunction with the Hsinchu City Bureau of Cultural Affairs and the Hakka Affairs Council (客家委員會) the village has been revitalized in recent years and the promotion of Hakka culture, cuisine and history has made it as important location for the people of Taiwan to travel to learn about the nations history.

Hsinpu has several historic ancestral homes that are quite similar to the Wu Zhuo-Liu Memorial House and if you’re interested in Taiwanese history, Hakka history or viewing the beautiful Hakka architecture of the past, a day-trip to Hsinpu will not only allow you to view some of these historic homes but also allow you to enjoy some amazing Hakka culture and cuisine at the same time.

Some of the other historic houses in the village include:

- Chen Family Ancestral Home (新埔陳氏宗祠)

- Chang Family Ancestral Home (新埔張氏宗祠)

- Liu Family Ancestral Home (新埔劉祠)

- Pan Family Ancestral Home (新埔潘屋)

- Chu Family Ancestral Home (新埔朱氏家廟)

- Lin Family Ancestral Home (新埔林氏家廟)

- Fan Family Ancestral Home (新埔范氏家廟)

*There isn't a lot of information available in English about these beautiful ancestral homes, but I'll be making a post about them in the coming weeks to explain them in a little more detail.

The Wu Zhuo-Liu Memorial House (like most of the houses listed above) is a traditional style Hakka “sanheyuan” (三合院) courtyard style home that is most identifiable by it’s “U” shaped design. The house was constructed sometime around 1840 and was the home where Wu Zhuo-Liu grew up and also where the rest of his family has lived and farmed up until recently.

Sanheyuan-style homes were very common in Taiwan before the Japanese Colonial Era and are often still quite prevalent throughout the countrysides of Taiwan. The problem for these older buildings is that the majority of them have become dilapidated over the years and in most cases have been abandoned or are being demolished in favour of a more modern style home. Preserving them can often be a bit difficult due to the humidity of Taiwan and the amount of earthquakes that rock the island.

Link: Hsinpu Ancestral Shrine (Already demolished)

The two longer wings of a sanheyuan are known as the “Hu-Long” or the “protecting dragons” (護龍) and is where you would find the bedrooms, living rooms, kitchens, dining rooms, etc. The main section of the building that connects to the two wings is sometimes translated into English as the “Inner Protector” (內籠) but is also what I usually refer to as the “Ancestral Hall” (室德堂) in these Hakka-style homes. In truth it is a bit difficult to literally translate what “室德堂” means into English but in simple terms it is the central part of the home where you’d find not only the main entrance to the house but also the ancestral shrine which meets you at the front door.

While these courtyard-style homes are prevalent throughout Taiwan and not unique to Hakka culture, one of the things that differentiates a Hakka home from some of the others is the ornate decorations on the roof and exterior walls. If you visit this home (or any of the others in Hsinpu), be sure to pay attention to the beautiful ceramic designs on the roof and the awnings which have been beautifully re-coloured and restored during the restoration process.

Link: Synapticism - A Traditional Home in Dacun 大村三合院

Link: Synapticism - Sanheyuan homes in Taiwan

Now that the home is open to the public, the rooms have been emptied and displays have been set up which not only introduce the life of Wu Zhuo-Liu and his family but also the function of each room. There are displays in the kitchens that help teach the people of today as to how people in 1840s Taiwan lived. The displays and exhibits set up within the house are non-intrusive and allow people to learn about the home in a way that doesn’t involve too much modern technology.

If you visit you should also make sure to tour the surrounding grounds of the building and check out the historic trail nearby where you’ll find a nice little lake as well as beautiful Taiwanese cypress trees and also a bit of nostalgia for an old Canadian like myself - Maple trees!

Getting there

Getting to the Wu Zhuo-Liu Memorial Home can be a bit difficult if you don’t have your own means of transportation. Unlike some of the other homes I mentioned above, this one is not situated within the downtown area of Hsinpu village. The home is on the road that connects Hsinpu Village (新埔) in Hsinchu County with Longtan Village (龍潭) in Taoyuan.

There is a bus that connects both villages but it only runs three times each day and you’re likely to get stuck waiting by a rice paddy for a few hours if you choose this option.

If you absolutely have to rely on public transportation I would recommend taking a train or bus to Jhudong (竹東) and from there transferring to a bus that takes you into the downtown area of Hsinpu village and then hiring a taxi.

There are quite a few cool things that you can see while walking around the downtown core of Hsinpu, so I recommend a stop by the historic town to check out some of the historic mansions, temples and of course to eat some Hakka flat noodles (客家粄條).

Address: #10, Jupu Village. Hsinpu Township, Hsinchu (新竹縣新埔鎮巨埔里五鄰大茅埔10號)

The recent renovation and restoration of the iconic author’s family home is not only an attractive destination for lovers of Taiwanese literature, but also those who respect the contribution Mr. Wu made to help promote the idea of Taiwanese identity to the world.

The subjects of his books dealt with topics that were quite sensitive when they came out but stand up to the test of time and still help the Taiwanese of today understand their history and why they should be proud to be Taiwanese.

The house is beautiful and walking around a traditional home like this can also teach people what life was like in Taiwan before all these modern high rise buildings were constructed. If you are in the area, I recommend a visit and think that a walk around the property can be a great learning experience.

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Shots)