No matter where you go in Taiwan, it’s highly likely that you’ll encounter a 7-11 or a temple along the way - finding either is about as simple as finding a cup of coffee, and when you’re a tourist, you’re blessed with a multitude of choices to compete for your precious, but limited travel time.

For most people, visiting one or two of what are considered Taipei’s ‘Top Three’ temples is more than enough ‘temple-time’ during a short visit to Taiwan, but there are a number of impressive places of worship in the capital, as well as around the country, where tourists can spend time learning more about the history and culture of this country than they ever will in most of its museums.

I’ve been writing about Taiwan for almost a decade now, and even though I’ve spent a considerable amount of time recommending that people travel outside of the capital in order to better understand, and enjoy all that this beautiful country has to offer, it’s also important to face the fact that not every tourist has the opportunity, or the time to make their way down south. So even though I’d personally highly recommend anyone who visits Taiwan to pay a visit to Tainan’s Confucius Temple, its Grand Mazu Temple or Lukang’s Longshan Temple over most of the places of worship on the ‘Top Three’ list above, like I said, not everyone has the ability to leave Taipei.

Fortunately, there are a number of historic places of worship within the Greater-Taipei area that wonderfully compliment the city’s so-called ‘Top Three’ temples, so if you’ve discovered, like I have, an interest in visiting this sort of destination, here are some of the others I recommend checking out while you’re in town:

Taipei Confucius Temple 台北孔廟 (Datong District)

Huguo Rinzai Temple 臨濟護國禪寺 (Datong District)

Songshan Ciyou Temple 松山慈佑宮 (Songshan District)

Taipei Tian Hou Temple 台北天后宮 (Ximen)

Guandu Temple 關渡宮 (Beitou District)

Puji Temple 普濟寺 (Beitou District)

Zhinan Temple 指南宮 (Wenshan District)

Bishan Temple 碧山巖 (Neihu District)

Today, I’m going to introduce another one of the city’s more prominent places of worship, and one that should be on your list of places to visit if you have some extra time while you’re in town. Boasting a history that is arguably longer than any other place of worship in Taipei, there’s certainly something special about this temple, but to tell the truth, it’s also somewhat of a confusing place as even locals have a difficult time understanding its significance.

Most commonly referred to either as Jiantan Temple (劍潭寺), or Jiantan Historic Temple (劍潭古寺), what I personally find interesting about this temple is the addition of the word “ancient” or “historic” (古) to its title in both Chinese and in English. There are surprisingly very few places of worship in Taiwan that make the concerted effort to put the word ‘historic’ directly in their name - although in some cases I think they’d prefer you just assume that’s the case - nevertheless, as one of Taipei’s ‘first’ places of worship, this one holds a special place within the history of the city.

The other thing that I think is important to point out about the name of this temple is the name ‘Jiantan’ (劍潭), which is probably confusing for tourists who might not be so familiar with Taipei’s geography. These days, the name ‘Jiantan’ is more or less synonymous with the Jiantan MRT Station (劍潭捷運站), which is home to Shilin Night Market (士林夜市), another one of Taipei’s most popular tourist destinations. Unfortunately, if you’re thinking that a visit to this temple could be combined with a visit to the night market, you might be disappointed. It’s actually not that close.

Never fear, though, as I move on below, I’ll provide a detailed explanation of the temple’s confusing history, how you can get there, all of which should help anyone who reads this better understand the temple, its special architectural design, and ultimately the history of the area we refer to as ‘Jiantan’ today. Before I start though, I have to say that even though this temple is one of the city’s oldest places of worship, it unfortunately doesn’t receive as much attention as it deserves, and very little has been written about it in the English-language, so I hope this article answers any questions you might have about it.

Jiantan Temple (劍潭古寺)

Legend has it that during the 17th Century, while Koxinga (鄭成功) and his army were sailing up the Keelung River, on their way to remove the Dutch from the island, they came upon a sudden and massive storm caused by river serpents. Attempting to prevent them from going any further, the storm was so violent that many in the army wanted to turn around. Koxinga, being the ever-so-clever pirate and experienced captain, was undeterred by the serpent’s interference in his plans, drew his sword and subdued the serpent. However, while in the midst of the fierce battle, his ‘sword’ was lost in the deep pool of water where the serpent lived.

For those of you who are unaware, the words “jian” (劍) and “tan" (潭) when put together basically translate as “Sword Pool” or “Sword Pond,” so even though the Koxinga legend is just local folklore, he was such a prolific figure in Taiwan’s history that a story about him mistakenly dropping his sword into a pool of water was reason enough to give a place a name.

Obviously, when it comes to the origin of the name, historians point to factual events that took place between Dutch traders, and the local indigenous people, but with regard to this temple, the legend of Koxinga is of particular note as you’ll discover later.

Its important to note that there was once a pond along the banks of the Keelung River that had been referred to as “Jiantan” for several hundred years. Located at a point of the river where the it curves between the areas we know today as Dazhi (大直) and Shilin (士林), that pond has since disappeared due to river diversion projects that sought to control water levels and prevent parts of the city from flooding during typhoons.

Today, the area we refer to as Jiantan covers several hundred hectares of land within the city, and even has a mountain that shares the same name.

Link: Jiantan Mountain (劍潭山)

If one legend weren’t enough, another explains that in 1634 (崇禎7年), a monk named Huarong (僧侶華榮和尚) was dispatched from his monastery on Putuo Mountain (普陀山) to deliver a stone statue of Guanyin to Taiwan. Arriving in Taiwan at the port in Tamsui (淡水), he continued south on the road to Keelung (基隆), but along the path he encountered a massive red snake that was blocking the way. Personally, I’m not particularly a huge fan of snakes, and if I encountered one while hiking in Taiwan, I’d likely turn around, but for Huarong, this was deemed as an auspicious event.

Note: The number ‘eight’ is an auspicious number for Buddhists, referring to either the Dharma Wheel (法陀) or the Eight Great Bodhisattvas.

Instead of taking off like I would have done, he set up camp for the night where the Buddha appeared before him in his dreams and instructed him to go to the local port (probably in Bangka), and solicit donations from eight merchant captains. When he woke up, he made his way to the port where he came across the eight ships in his dream and when the merchants on the ships heard his story, they donated graciously to his cause. With the money donated by the local merchants, Huarong had a thatched hut built on the location where he came across the red snake, and that became the home of the Guanyin Statue, instead of its original destination in Keelung.

Later, in the early eighteenth century, the thatched hut, which had become known as the Guanyin Pavilion (觀音亭) was replaced by a more formal temple, known as the “Western Temple” (西方寶剎). That name, however, wasn’t one that would remain for very long as the temple was renamed Jiantan Temple (劍潭寺) in 1746 (乾隆11年).

Over the next century, Jiantan Temple became one of the more prominent Buddhist temples in northern Taiwan, resulting in a number of restoration and expansion projects to accommodate the number of monks who came to serve at the temple. Then, when the abbot of the Bangka Longshan Temple (艋舺龍山寺) took administrative control of the temple, he once again oversaw another expansion project that would not only benefit Jiantan Temple, but Longshan Temple as well with monks being able to travel back and forth between two of northern Taiwan’s most important temples.

For the next half century, things more or less stayed the same at the temple, but when the Japanese took control of Taiwan in 1895 (明治28年), the situation changed almost overnight. When the Governor General of Taiwan, Kodama Gentaro (兒玉源太郎) requested monks from the Rinzai school (臨濟宗) of Zen Buddhism to come to Taiwan to promote Japanese Buddhism, the influence of Japanese-style Buddhism started taking over on the island, and Jiantan Temple was promptly converted into a Myoshin Temple (妙心寺).

The interesting thing to keep in mind was that during the Meiji Restoration (明治維新), which started decades before the Japanese took control of Taiwan, Buddhism was classified by the government as a source of foreign interference. It was during this time that the more than a thousand year old tradition of fusion between Buddhism and Shinto were forcibly separated with the Buddhist temples that were constructed next to Shinto Shrines torn down. Here in Taiwan, though, Buddhism, had a long established a foothold on the island thanks to places of worship like Jiantan Temple, thus they became one of the tools that the Japanese authorities used to help bring the two peoples together.

Ironic given that Buddhism was suppressed back in Japan.

From the outset, the Japanese brought Buddhist monks with them to serve roles within the military as ‘chaplain-missionaries’, offering spiritual guidance during the initial years of the occupation. In addition to serving the military, the monks began to construct language schools and charity hospitals where they would focus on improving the lives of average Taiwanese citizens as well as promoting Japanese-style Buddhism. Over the next few decades, the temple continued to grow, and between 1918 and 1924, the temple was completely reconstructed, making use of modern construction techniques to ensure its longevity. The irony however was that just over a decade after the rebuild was completed, the temple was then forced to relocate due to an expansion project at the Taiwan Grand Shrine (臺灣神宮), which was also located on Jiantan Mountain (劍潭山) to the rear of the temple.

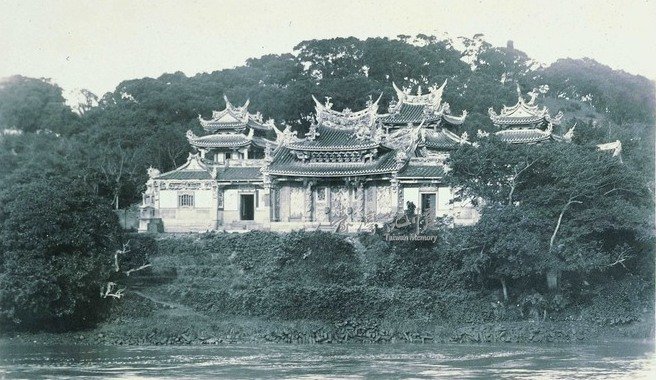

With insufficient funds available for the construction of a new temple, the administration came up with a plan to have the buildings completely deconstructed, and then reconstructed with the materials that could be salvaged in a new location. Migrating several kilometers away to the Dazhi (大直) area, the temple was carefully put back together again. However, the new plot of land that was allocated for the temple wasn’t nearly as larger as the original space, so alterations had to be made, and as you may have noticed from the historic photo above, it is considerably smaller today.

In its current location for nearly a century, Jiantan has been restored several times, repairing elements of the temple that have allowed it to remain intact while also bringing it back to life by refining the building’s decorative elements which were once its defining features.

As one of Taipei’s first major places of worship, predating many of the capital’s other major temples, Jiantan Temple has a long and storied history and while it’s not uncommon for places of worship to be moved to a new location, the experience of deconstructing the temple and sending putting it back together in another location is reminiscent of the nearby Lin An Tai Mansion (林安泰古厝), which had a similar experience.

In 2004 (民國93年), Jiantan Temple was officially recognized by the Taipei City Government under the Cultural Heritage Preservation Act (文化資產保存法) as a protected heritage building (歷史建築).

Link: 臺北市歷史建築列表 (List of Taipei City Protected Heritage Buildings)

Whether you refer to this temple as Jiantan Temple (劍潭寺) or Jiantan Ancient Temple (劍潭古寺), it’s up to you, but one of the things that sets this one apart from many of the other historic temples around Taipei is that it features a little park where it proudly displays its history. Some of the objects within the park, mostly stone tablets and pillars are things that you probably won’t see anywhere else in the capital, but are much more common in Tainan where historic temples are found on almost every street corner. If you visit the temple, I highly recommend you take some time to check out some of the objects on display, even though they are admittedly pretty old and in some cases the words that have been etched on the stone have started to fade.

Deities Enshrined at Jiantan Temple

As you saw from the history detailed above, from the outset, Jiantian Temple was dedicated to Guanyin (觀音), the Chinese version of Avalokiteśvara, the Buddha of Compassion. With a statue brought directly from Putuo Mountain (普陀山), one of China’s four sacred Buddhist mountains, it shouldn’t be much of a surprise to anyone that the figures enshrined within the temple are for the most part, Buddhist. That being said, similar to what you’ll experience if you visit Bangka’s Longshan Temple, which is also primarily a Buddhist place of worship, over the years, figures from Chinese folk religion have been added over the years to the shrine. In Taiwan, this is something that has become quite common, so within the temple you’ll also find shrines dedicated to ‘deities’ who you won’t traditionally find in Buddhist temples elsewhere, especially in other countries where Buddhism is the predominant religion.

Guanyin (觀世音菩薩) - As noted earlier, Jiantan Temple was (historically) dedicated primarily to the Buddha of Compassion, Guanyin (觀音), one of the most prolific Buddhist figures in Taiwan. Within the shrine room, you’ll find several different statues dedicated to different incarnations of Guanyin, with two large statues of a sitting Guanyin on either side of the main shrine. The original statue has since been moved to a new location within the main shrine and is somewhat difficult to see amongst the crowd of Buddhist figures in the main shrine. The most important difference between the various statues of Guanyin is that the original is regarded as a ‘Child-Bearing Guanyin’ (送子觀音). In front of the historic statue, you’ll find a version of a sitting Guanyin and as is usually the case, she is accompanied by her two acolytes, a pair of children who went to her side while she was meditating at Mount Putuo, Longnu (龍女) and Shancai (善財童子).

Shakyamuni Buddha (釋迦牟尼) - In one of the most recent changes to the ‘ancient’ temple, a statue of Shakyamuni Buddha was added to the main shrine in the post-war period. The jade statue was added shortly after the Foguangshan Organization took over administrative control of the temple, which is something I’ll talk briefly about below. The statue holds a ‘seal’ (降魔印) for subjugating demons. The interesting thing about the statue is that its appearance isn’t typical for a Chinese-style Buddha statue. It appears more as if it came from South East Asia, more specifically the Myanmar area. It possibly came to Taiwan with Chinese refugees from the Yunnan region, but I’m not particularly sure about its origin. During my visit to the temple, I inquired about the design of the statue, and the person who I was talking to was surprised that I could tell the difference between an image of the Buddha from Myanmar compared to one that you’d typically find in Taiwan, but the explanation I received as to its origin wasn’t particularly convincing, and its likely that there were some politics involved that they didn’t really want to mention.

The Prince of Yanping (延平郡王) - Looking back to the legends of the naming of Jiantan, you might remember that one of the local folklore stories claims that Koxinga (鄭成功) threw his sword into the pond to dispatch a violent serpent that was preventing them from advancing. What I didn’t mention was that Koxinga would later go on to defeat the Dutch and proclaim a kingdom of his own in the south of Taiwan, known as the Kingdom of Tungning. Given that Koxinga’s legend shares a relationship with the local area, and his being deified in Taiwan after his death, it shouldn’t be a big surprise that there is a shrine dedicated in his honor at the temple. When you find a shrine dedicated to Koxinga in Taiwan, he’ll either be referred to as the Prince of Yanping (延平郡王), a title bestowed upon him by a Ming Emperor, or Kaishan Shengwang (開山聖王). Interestingly, if you climb Jiantan Mountain to the rear of the temple, you’ll find an entire temple dedicated to Koxinga, known as the Taipei Koxinga Temple (成功廟開臺聖王).

The Eighteen Arhats (十八羅漢) - On either side of the Main Hall, you’ll find wood-carved representations of the ‘Eighteen Arhats’, who are basically like the twelve disciples of Jesus. The original followers of the Buddha, the ‘Arthats’ are figures each of whom has attained enlightenment, but have dedicated their lives to being reincarnated on earth until everyone attains enlightenment. A common image in Taiwan, you’ll find nine of the arhats on each side of the shrine, and each of them appears quite differently, so you might want to take a moment to look at them as they are all interesting characters.

With regard to the statues in the shrine room, there has been somewhat of an unresolved controversy in recent years as the administration of the temple is now overseen by the large and powerful Foguangshan (佛光山) organization. The controversy revolves around a differing outlook between the followers of the original temple and the new organization that took over. Long story short, the main shrine was originally dedicated to Guanyin, but it was adjusted to provide a seat to the Shakyamuni Buddha, instead.

The historic statue of Guanyin was thus moved to a level below the Buddha, which, angered the followers of the temple. Likewise, some of the other statues of Guanyin that were originally in the temple were moved outside of the temple where they would get rained on and polluted from dirty air.

In the time since the controversy, which made headlines across the country, changes have been made to bring the statues of Guanyin back inside the temple, but the main shrine continues to place the Buddha in the main seat, which doesn’t particularly reflect the history of the temple.

Link: 主神換位 劍潭古寺主位觀音變佛陀 (TVBS)

Jiantan Ancient Temple Timeline

Obviously, Jiantan Temple couldn’t be considered an “ancient” temple if it didn’t have a long history. As one of the first Buddhist places of worship in Taipei, there is clearly a long and interconnected history that coincides with the development of Taiwan’s capital into the high-tech economic powerhouse that it is today. That being said, the history of the temple tends to be a little confusing, and not very well detailed in either Chinese or English. I’ve done my best to put together a list of events with regard to the temple’s history that should give readers an idea of the timeline of events over the past three centuries of its history.

Click the dropdown below to read more:

-

•1634 (崇禎7年) - Buddhist Monk Huarong (僧侶華榮和尚), travels to Taiwan from his monastery on the famed Putuo Mountain (普陀山) to welcome a stone statue of Guanyin to the island.

•1718 (康熙57年) - A Buddhist temple named the ‘Western Temple’ (西方寶剎) was established along the banks of the Keelung River with Jiantan Mountain to its rear.

•1746 (乾隆11年) - Jiantan Temple (劍潭寺) is officially established.

•1773 (乾隆38年) - The temple goes through its first period of restoration.

•1800 (家慶5年) - The temple goes through another period of restoration.

•1836 (道光17年) - The temple goes through a period of expansion, making space for an official residence for the monks who stayed on-site.

•1843 (道光24年) - The abbot of Longshan Temple in Bangka assumes administrative control over the temple, and materials are donated to once again expand and restore the grounds.

•1895 (明治28年) - The Japanese Empire takes control of Taiwan.

•1899 (明治32年) - During the Japanese era, the temple became a Myoshin Temple (妙心寺), part of the Rinzai Sect (臨濟宗) of Japanese Buddhism.

•1914 (大正3年) - The monks living at the temple initiate a fundraising campaign to have the temple reconstructed.

•1918 (大正7年) - With the fund raising campaign completed, famed craftsman Chen Yingbin (陳應彬) is contracted to oversee a complete overhaul and redesign of the temple.

•1924 (大正13年) - The reconstruction project on the temple is completed, with a brand new traditionally Chinese-style design fused with Japanese elements and construction techniques.

•1937 (昭和12年) - Shortly after the expensive reconstruction of the temple is completed, an expansion project at the nearby Taiwan Grand Shrine (台灣神宮) forces the temple to relocate to another location a short distance away. Due to a lack of funds, the temple is more or less deconstructed, and then reconstructed in its original location.

•1945 (民國34年) The Second World War comes to an end and the Republic of China takes control of Taiwan

•1978 (民國67年) - A restoration project takes place, repairing and restoring some of the aging elements of the temple, and replacing the roof tiles with Taiwanese-style yellow tiles (黃色琉璃瓦).

•2004 (民國93年) - The temple is officially recognized as a protected heritage building (歷史建築).

•2007 (民國96年) - A restoration project takes place that restores the shape and design of the roof to its original 1924 design and all of the original decorative elements are carefully reproduced to reflect the original appearance of the temple.

•2017 (民國106年) - A newly constructed Guanyin Shrine is consecrated within the temple.

Architectural Design

The story of Jiantan Temple’s architectural design is a bit of a complicated one, and is something that you may have noticed in the timeline above has been altered several times, throughout its three-century long history. Over the years, the temple has been renovated, expanded, restored, reduced in size, and ultimately moved to an entirely new location.

Fortunately, thanks to the dedication of Japanese-era photographers, we have a pretty good idea of how it originally appeared prior to its migration, as you’ll have seen in some of those photos above. I’m not going to spend too much of your time talking about the temple’s past glory, or what is missing. Instead, I’m only going to focus on what you’ll experience when you visit today, which itself is a beautiful place of worship, full of complex design and decorative elements, some of which are uncommon in Taipei today.

If we take into consideration that the temple migrated to its current location during the Japanese-era, you’ll also discover that even though it maintains many traditional Taiwanese temple features, it is also a case-study in the fusion of Taiwanese-Japanese design of the era, which makes it quite special.

As I mentioned earlier, when the temple was forced to migrate, they lacked the necessary funds to construct an entirely new building. Thus, it was decided that instead of demolishing the original temple that they would have it deconstructed as carefully as possible in order to recycle the original materials to bring it back to life. Unfortunately, due to a lack of space on the plot of land that was allocated to the temple, and the difficulty of deconstructing the original, the end-result was a temple that was considerably smaller than the original.

The current design retains much of the original wood and stone that was used to construct the temple, which have been recycled. The size of the building is officially measured in ‘bays’ (開間), an ancient style of measurement that you won’t see mentioned very often in Taiwan these days, except for at historic places of worship like this. Essentially a ‘bay’ was the space between columns that held up the roof. Generally-speaking that was about 3.6 meters in length. Using this method, Jiantan Temple is officially eleven bays in length (面寬十一開間), which makes it just about 40 meters (131 feet) wide.

Keeping with the traditional design of a Hokkien-style temple, the facade of Jiantan Temple resembles that of the Front Hall (前殿) at Lukang’s famed Longshan Temple (鹿港龍山寺) in that it features a ‘Five Door Hall” (五門殿) style of design. In this style of design, there is a central wing that features the temple’s three main doors, with separate ‘dragon’ and ‘tiger’ wings (龍虎翼廊) on either side. Both of the wings feature a Swallow-Tail Roof (燕尾屋脊), which are equal in height, while the central portion is much higher. This style of roof, which is indicative of Hokkien-style architectural design differs from the typical style of ‘hip-and-gable’ roof that you’ll find at many Chinese, Japanese or Korean-style Buddhist temples. Yet it is one of the most common styles of architectural design with regard to the historic temples, mansions and ancestral halls around Taiwan.

Essentially, a ‘Swallow-Tail Roof’ is a roof that features an upward-curving ridge, resembling the tail of a swallow, and is typically adorned with a number of decorative elements, which are most often porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕). Depending on the amount of cash you have available, and how much you want to show off your wealth, this style of roof could be either single or dual-layered to add even more complexity. In this particular case, you might think with the varying heights between the wings and the central portion of the building that it is dual-layered, but it’s actually only a single-layer roof as the roofs over the wings are independent of the other. Nevertheless, despite the curvature of each of the roofs being one of their key features, you’ll notice that the mid-section is the most prominent as the two wings only feature half-curves, and neither of them reach as high as the mid-section.

One area where the Hokkien-style Swallow-Tail roof resembles that of a hip-and-gable roof is that the roof eclipses the base of the building in size, extending well beyond the front of the building. Thus, to help support the weight of the roof, you’ll find a number of pillars used for support both within the interior and on the exterior as well. The most prominent of these support pillars are located on either side of the middle door, and are beautifully-carved stone dragons that encircle the columns.

Link: Hokkien Architecture (Wiki)

While the temple may seem somewhat subdued in its design from afar, the devil is really in its finer details as the closer you look, the more exquisite you’ll discover its decorative elements are thanks to the 2007 restoration work that went into the temple (mentioned on the timeline above). It was at this time that the yellow cylindrical bamboo-like tiles (燒筒板瓦) that covered the roof were completely replaced as were almost all of the cut-and-stick decorations (剪黏), which are integral to Hokkien-style design.

The newly-designed decorative elements were part of a long research project that ultimately restored the original elements that you would have found at the original temple, when it was still in its original location. In this case, the temple contracted Pan Kundi (潘坤地), a master craftsman who is most well-known for his contributions to the restoration of Dalongdong’s Bao-An Temple (大龍峒保安宮), a Taiwanese national treasure, and recognized by UNESCO for its contribution to the preservation of cultural heritage.

One of the problems that might arise when you visit the temple today is that the ‘finer details’ mentioned above are abundant, and you may find yourself spending quite a bit of time looking at the decorative elements on top of the ridges, between the ridges, and along the ends of each of the them and contemplating their meaning. Never fear, I’ll do my best to answer some of those questions with the help of my telephoto lens!

Starting with the more obvious design elements, you’ll notice the ‘Double Dragon Pagoda’ (雙龍寶塔) directly in the middle of the apex of the roof. This is a decorative element that is common at Buddhist temples, and represents a number of important things - First, it is used to ward off evil spirits and fire, but it also represents ‘filial piety’ and ‘virtue’. Another way of interpreting it is by explaining that ‘pagodas’ were traditionally buildings where Buddhist texts were kept, so having the dragons encircling the pagoda in this way is a way of ‘protecting the Buddha’ or ‘precious things’.

The next thing you’ll probably notice is that on each of the ridges, there is a dragon-like creature facing toward the pagoda. In fact, this creature is referred to as an “Aoyu” (鰲魚), and is basically a carp that is in the process of transforming into a dragon featuring the head of a dragon and the body of a fish. Similar to the Dragon-Pagoda’s nature of helping to ward off fire or other disasters, the Aoyu are known for their ability to ‘swallow fire and spit water’ meaning that they’re also there to offer protection to the temple.

Conveniently located just under the two Aoyu in the mid-section, you’ll find one of the ‘Four Heavenly Kings’ (四大天王) accompanying them. Known as important Buddhist figures with regard to ‘protection’, in Mandarin, the names of the kings go together to form the idiom “fēngtiáoyǔshùn” (風調雨順), or “seasonable weather with gentle breeze and timely rain,” and by this point you’re probably wondering just how often temples burn to the ground. With the amount of candles and incense that are burnt in these temples, it probably shouldn’t be too surprising that it does, unfortunately, happen from time to time.

The design of each of the kings is slightly different, but its important to offer a bit of detail:

Virulhaka (增長天王) - holding a jeweled double-edged sword

Vessavana (多聞天王) - holding a jeweled umbrella

Dhatarattha (持國天王) - holding a pipa (a traditional musical instrument)

Virupakkha (廣目天王) - holding a dragon in his hand

Link: Four Heavenly Kings (Wiki)

Once again, looking carefully along the Xishi Ridge (西施脊), the flat part of the top ridge, you’ll find some pretty intricate decorative elements in the space between the Four Heavenly Kings. Directly under the Dragon Pagoda, there is a mural that depicts the folklore story of ‘Guanyin conquering the phoenix’ (老古板的古建築之旅). The story, which originated in the Song Dynasty (宋朝), is a popular one in Taiwan that has been converted into a Taiwanese opera, which is often performed outside of temples. In the story, “Dapeng” (大鵬金翅明王), the Chinese manifestation of the Hindu deity Garuda turned into a human and came to earth to wreak havoc, forcing Guanyin to appear to make an appearance and back him under control. Legends regarding the mythical ‘Dapeng Phoenix’ appear throughout Chinese history, but in most of the stories, one of the commonalities is that it is often subservient to the Buddha or Guanyin.

One thing that confused me, and sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole looking for information, were the five animals located below the Guanyin mural. It is common to find ‘four’ animals depicted in this particular space within Taiwan’s temples, known as the ‘Auspicious Four Beasts’ (四祥獸), most often represented as a Tiger, Leopard, Lion and Elephant (虎豹獅象) - just like the so-called ‘Four Beasts Mountains’ in Taipei. Once again, as with the other decorative elements discussed so far, the presence of the beasts is meant to help suppress evil spirits and protect the temple. In this case, however, there are ‘Five Auspicious Beasts’ thanks to the inclusion of a Qilin (麒麟), a mythical Chinese chimera.

Link: Four Beasts Hiking Trail (四獸山步道)

Swallow-Tail roofs not only feature an upward-curving ridge at the apex of the roof but also often have eaves that descend from the ridge to the lower section of the roof where you’ll find a platform for additional decorative elements. Known in Taiwanese as the ‘paitoh’ (牌頭), you’ll find another set of elaborate murals at the end of each of the roof’s eaves.

There are two murals in the mid-section, and another one on each of the ends of the eastern and western wings. Two of the murals depict events from the life of the Buddha, while the other two are related to Guanyin.

Speaking of the wings, they feature similar decorative elements along their ridges, but in both cases are a bit more subdued, with simple depictions of peonies (牡丹), phoenixes (鳳), qilin (麒麟) and peacocks (孔雀).

Link: Animals & Mythical Creatures (Buddhist Symbols)

Moving on from the roof, located directly in front of the middle door in the centre of the building, you’ll find a beautifully designed Tiangong Incense Cauldron (天公爐) that features the words ‘Taipei Jiantan Historic Temple’ (台北劍潭古寺) carved on the bowl. The design here is slightly different than what you’d see at other places of worship in Taiwan as it is quite narrow compared to the cauldrons you’ll find at other temples. What remains the same is that you’ll find 'dragons grabbing pearls’ (雙龍戲珠) on either side and an octagonal-covered roof with three legs that represent a ‘tiger’ (寅), ‘horse’ (午) and ‘dog’ (戌), which are considered the ‘triad of heaven, earth and man’ (天地人).

Note: The ‘double dragons grabbing pearls’ (雙龍戲珠) are part of an ancient Chinese-language idiom that symbolizes humanity’s constant pursuit of happiness. It has also become an important image with regard to weddings as the harmony between husband and wife and mutual respect, humility and tolerance.

On either side of the cauldron you’ll find the beautifully-carved traditional stone dragon pillars (龍柱) that I mentioned earlier. The pillars, which aren’t from the original temple, are thought to be a product of the early 1900s, although you won’t find a date carved on them to prove that. Still, they’re well over a century old and have recently been given a bit of restoration. Featuring dragons that encircle each of the pillars. You’ll also find depictions of people and animals walking along each of the dragon's backs.

Directly in front of the cauldron, you’ll find a stone-carved Dragon Ramp (龍陞) between the ground and the platform in front of the doors. Also referred to as a ‘Royal Ramp’ (御路), the sloping ramp is reserved for the passage of royalty, or for whenever one of the statues has to be moved outside of the temple. Even though Taiwan doesn’t have any royalty, and the only royals to have ever visited the country were from the Japanese imperial family, these sloping ramps are a common feature among the temples you’ll find across the country.

Another common feature that the temple shares with most other places of worship in Taiwan is that there is a name plaque located above the middle door. The beautifully inscribed plaque (牌匾) features the temple’s name scripted in calligraphy and obviously if you take a look at it, it’s in pretty good shape, but in this case you can see the date it was placed, which was in August of 1981 (民國70年8月).

Speaking of recent additions, the shrine is currently home to lacquered wooden sliding panels with golden latticed windows. The wood-carved latticed windows (木柵窗格) don’t actually look like typical ‘windows’, but they feature intricately carved floral designs with birds and peacocks.

Finally, if you find yourself standing on the platform by the central door, you’ll discover that there are some really intricate and beautifully hand-carved wooden figures (木雕) that are used to decorate the trusses and eaves that connect to the pillars, which are instrumental in working together to help to support the weight of the roof. The carvings, which feature lions and murals, like the lattice windows below are all painted gold and make the exterior of the temple much more beautiful.

Before I move on to briefly describing the interior of the temple, I think it’s important to note that if you search for images of the temple online, you’re going to notice a stark difference between some of the photos you’ll find.

Prior to 2007, the temple looked considerably different, and very much more ‘plain’ that what you’ll see today. As I mentioned earlier, the design of the roof was completely changed to reflect the temple’s original design and it was during that restoration project that most of the decorative elements that I’ve described above were added. Given that the master craftsman mentioned above is known for not only his skills with traditional Hokkien cut-porcelain carvings (剪瓷雕), but also his wood-carving skills, it’s safe to say that all of the decorative elements that we enjoy today are thanks to his genius and hard work.

I won’t spend too much describing the interior of the temple, simply due to the fact that Hokkien-style Buddhist temples place an incredible amount of detail on the decorative elements of the exterior of the building while the interior is much more subtle. That being said, it has to be mentioned that, like the Lukang Longshan Temple, the temple features a beautifully designed ‘caisson’ (八卦藻井) in the main shrine room. Also known as a “Ba-Gua ceiling,” it would be an understatement to say that it is a masterpiece of architectural design. Octagonal in shape, each side of the caisson symbolizes eight symbols in Taoism that represent the fundamental principles of reality.

Somewhat difficult to describe properly, a caisson is basically a sunken layered panel in a ceiling that raises above the rest of the ceiling almost as if there were a dome above it. The layers of the caisson are often beautifully decorated and with a design at the center which in this case is just a painted flower that has a lamp hanging from the middle.

The most amazing thing to keep in mind about these caissons is that they are designed using expertly measured interlocking pieces that connect together in a way that means that neither beams nor nails are used to keep them in place. They simply lock together to form a six-layer deep spider-web of beauty. It takes a considerable amount of skill and patience to make one of these, so if you visit, one of the first things the people at the temple will do is make sure you take note of it.

As mentioned above, the interior of the temple is split into three sections with the main shrine in the middle. The wing to the left of the main shrine room is used for administrative purposes while the wing on the right is home to the Koxinga Shrine. The passage ways from both of the wings feature a couple of objects that should be noted. First, on the left wing, you’ll find a drum hanging within the passageway while on the right wing you’ll find a large stone bell, both of which are common within Buddhist temples as a way of indicating the time, attracting crowds, and announcing the beginning of preaching.

Finally, one last thing I’d like to point out is the ‘Dragon Altar’ (案桌) in the middle of the shrine - the altar features a painted dragon with the words ‘Jiantan Buddha’ (劍潭佛祖) on it. Likely one of the oldest parts of the current temple (save for the Guanyin statue), the altar dates back to the reign of Emperor Daoguang (道光) of the Qing Dynasty, placing it somewhere between 1821 and 1850. On either side of the altar, you’ll find some stone pillars with calligraphy engraved on each of them. Speaking to the history of the temple, they tell a story of how the migration of the temple to its current location wasn’t an optimal decision, but was forced upon them by the Japanese. I’d attempt to translate the text, but I have to admit that its beyond my level. Nevertheless, the sentiment is a bit salty.

The text is provided below for anyone interested:

Note:「寶劍劫灰塵爐火重新光大直,澄潭涵法雨川流終古擁觀音」and「庚辰劍潭古寺移築大直」

Getting There

Address: #6, Alley 805, Bei-An Road, Zhongshan District, Taipei

(臺北市中山區北安路805巷6號)

GPS: 25.085910, 121.554330

Conveniently located a short walk from an MRT station, visiting the Jiantan Historic Temple is actually quite straightforward, and is easily accessible for any tourist who’d like to visit. That being said, there are faster options than the MRT if you’re taking public transportation, so I’ll provide directions for both the MRT and the bus routes that will get you there below.

MRT

Located across the Keelung River from Taipei in Neihu’s Dazhi (大直) neighborhood, taking the MRT is obviously one of the most convenient methods of getting to the temple. That being said, even though the MRT drops you off pretty much at the temple’s doorsteps, its convenience doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the quickest way to get there as the Brown Line trains are considerably slower than the normal underground MRT, and you’ll likely have to pass by Songshan Airport on your way there.

Nevertheless, if your preferred method of transportation is to take the MRT, simply get yourself on the Brown Line either at Zhongxiao Fuxing (忠孝復興) or Nanjing Fuxing (南京復興), heading in the direction of Nangang Station (南港捷運站). Getting off the train at Jiannan Road Station (劍南路捷運站), you’ll take Exit #1 and walk straight along Beian Road (北安路) where you’ll notice Jingye Park (敬業公園) on your right and the temple about a minute away on the left.

Bus

Similarly, given that the Jiannan Road MRT Station is located next to the Miramar Shopping Mall (美麗華百樂園), famed for its giant roof-top ferris wheel, there are a number of bus routes that will help you get there just as easily as the MRT. The closest bus stop to the temple is the Jiannan Road Stop (捷運劍南路站), directly in front of the MRT Station, so if you end up taking a bus, the walking route to the temple follows the same route.

Given the popularity of the Miramar Shopping Center, there are far too many bus routes that service this bus stop, and since Internet links for these things in Taiwan are notoriously unstable, I’m not going going to link to each of the routes individually here. I highly recommend travelers make use of the Taipei eBus website, or download the Bus Tracker Taipei app on your phone (Android | iOS) or use the Real-Time Bus Tracking service offered on the eBus website.

Here are the following routes that service the Jiannan Road Stop: Neihu Express Line (內湖幹線), Red #3 (紅3), Blue #26 (藍26), #28, #33, #42, #72, #208, #222, #247, #256, #267, #268, #287, #556, #620, #646, #681, #683, #902, #957, #1801

Youbike

If you’re feeling adventurous, you can easily hop on one of Taipei’s convenient shared Youbikes and make your way along the Keelung River all the way to Dazhi where you’ll be able to park the bike in front of the Jiannan Road MRT Station and make your way to the temple. If you’d like to make use of a Youbike, one of the best routes would be to grab a bike at the Yuanshan MRT Station (圓山捷運站), and make your way along the Dajia Riverside Park (大家河濱公園) where you’ll cross the pedestrian section of the Dazhi Bridge (大直橋), and from there making your way toward the Jiannan Road Station. There are of course a number of routes that you could take to get there, though, so I recommend opening up Google Maps on your phone and mapping out a bike route from wherever you’re starting from!

If you haven’t already, I highly recommend downloading the Youbike App to your phone so that you’ll have a better idea of the location where you’ll be able to find the closest docking station.

To be frank, I don’t really spend very much time in the Neihu area of Taipei. I’ve visited most of Taipei’s most important places of worship over the years, but this temple was one that I’ve always had on my list, but took quite a while to actually get around to. It’s not that I didn’t think it was important, or that it should be high on the list of places that people should visit when they’re in town, I just personally only find myself in that area when I’m hiking along the Jiantan Mountain ridge. Nevertheless, if you find yourself in the city and the temples are of particular interest to you, I highly recommend checking out some of those listed above, and if you’ve still got time left, head over to this one to check it out as well!

I suppose that doesn’t particularly sound like a rousing endorsement of the temple, but I’m not sure how much appeals to most short-term tourists. I have to say, though, that the temple was a lot more beautiful than I expected, and if the photos in this article are any indication, you’re in for a treat if you visit, especially since its a much more quiet place of reflection than some of the other major temples that tourists visit.

References

劍潭古寺 (Wiki)

劍潭 (Wiki)

劍潭寺 | Jiantan Temple (台灣宗教文化地圖)

劍潭寺 (國家文化資產網)

劍潭古寺 (台灣好廟網)

劍潭古寺 (Tony的自然人文旅記)

巴字第974號:劍潭古寺 (地球上的火星人)

中山區 劍潭古寺 — 隱身於熱鬧商場旁之臺北盆地最早古剎,有段被迫搬遷的過往 (Mobile01)

剪黏藝術欣賞(五) 劍潭古寺 (老古板的古建築之旅)

劍潭古寺 (淡水維基館)

Jiantan Temple (Travel Taipei)

Hokkien architecture | 闽南传统建筑 (Wiki)