I've been on a bit of a kick lately searching high and low around Taiwan for remnants of the Japanese Colonial Era. I've discovered that there is still a lot to be found but it just so happens that not everything I end up finding is in very good shape, photogenic or has a story to tell. Nevertheless I have spent a considerable amount of time searching the Internet up and down for clues as to something interesting and have been setting off to find it whenever I have the chance.

The Lunar New Year holiday this year was a short one so instead of planning a trip outside of the country, I decided that I would make several day trips around the northern part of the country to find a few things that I had on my list. My first trip ended up being a bit of a screw up as I drove all the way from home to Jhudong (竹東) in Hsinchu to get some more shots of the half-abandoned Timber Industry dorms.

Unfortunately upon arrival I took my camera out of the bag and upon taking the first shot I realized I didn't have either of my usual memory cards in my bag and my spares were also sitting on top of my memory card reader at home. I had to walk around an empty city looking for an open electronics store on the first day of the new year which was quite difficult.

Having learned my lesson I packed several cards in my bag and prepared for my next trip, a quick one to to southern most train station in Hsinchu - Xiangshan Station (香山車站). Xiangshan is known for its Wetlands (香山溼地), its "several hundred" year old Mazu Temple (香山天后宮) and its cute little wooden Japanese train station. A short walk from the station however is a huge (and somewhat out of control) God of Wealth (財神) temple which sits up on a hill above the main road that goes through the village.

I've never really been a huge fan of temples dedicated to the God of Wealth but I was only going to be passing by - I was actually looking for (what I thought was) a Japanese temple that Google Maps showed me was on the mountain somewhere behind the temple. The problem was that there was no road to the building on Google Maps, so I had to do a bit of exploring to find my own way.

With my cellphone in hand I walked around looking for a path that would lead me to the temple and after no more than five minutes I found a rugged-looking stone pathway that led up a hill and figured I hit the jackpot. When I reached the top of the hill I saw the temple sitting there and it looked like it was in great shape so I was really pleased with my find.

I had noticed an older lady off to the side doing some gardening work but was able to walk in unnoticed and did my thing getting shots of the exterior. Eventually I walked up to the door and pulled back some plastic sheets and walked into the shrine room. The little temple was just a one room shrine full of Buddhist statues, spirit plates and pictures of people who I figured were local people or patrons of the temple back in the day.

I got all the shots I needed and then walked outside and got more shots of the exterior before being noticed by the old lady who came over and looked at me quote oddly. She asked me in a somewhat unintelligible dialect of Mandarin: "Why are you here?" I replied that I was researching the Japanese Colonial Era and was interested in this building.

She replied back: "This is Taiwan, not Japan. There's nothing Japanese here."

The building seemed to have been built with Japanese design and from what I saw online was built in the later parts of the 1800's meaning it was constructed during the colonial era. The wooden construction and the roof seemed to point in that direction and the wood inside the building was made entirely of Hinoki Cypress (檜木) which is very popular with Japanese construction of that era.

I figured there must have been a communication error so I replied to her: "I know this is Taiwan, but this temple looks like it was Japanese design and origin." which brought on the same look of confusion on her face that I had on mine. I'm not going to lie, the lady seemed a bit off and I have had bad luck running into crazy religious people in the past so I wasn't going to keep pressing the issue. I thanked her for the quick chat and then walked off to take a few more pictures before leaving.

Internet research however makes the story of this interesting little temple a little clearer.

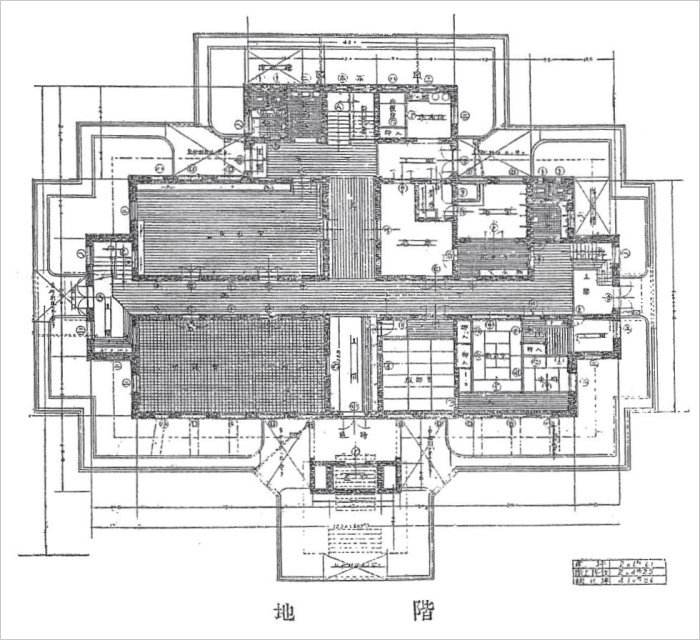

The history of this temple dates back to 1884 (明治17年) where it was originally constructed near the coast just behind Xiangshan's modest but historic Mazu Temple (香山天后宮). The original name was Yishan Temple (一善寺) and was a monastery style building constructed with a main hall and two halls to the sides. The temple worshipped Guanyin, the Buddha of Compassion and sought to promote Buddhist philosophy to the people of the area - more importantly the women who it offered specialized six-month "bhikkhuni" (nun) classes where women could take short-term monastic vows.

In 1935 however the devastating Shinchiku-Taichu Earthquake (新竹台中地震), one of the deadliest earthquakes in modern Taiwan history destroyed the temple. The following year it was decided that the temple would be relocated to a spot on the mountain nearby.

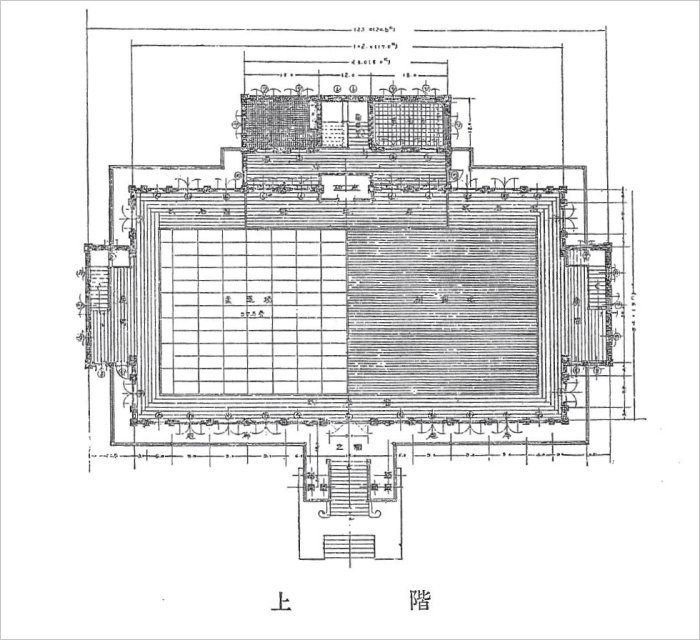

When the temple's reconstruction was completed it was renamed "Yishan Hall" (一善堂). The new version however was completely different than the original - It was a simple one room building with a main shrine dedicated to Buddhism and ancestral shrines on either side dedicated to the Zheng family (鄭家). Today there are several generations of spirit tablets (神位) and photos of the Zheng family.

While the main shrine of the temple is dedicated primarily to important figures within Buddhism, there are also elements of Taoism and Taiwanese folk-religion grouped together with the Buddha's which is typical of Taiwanese religious traditions.

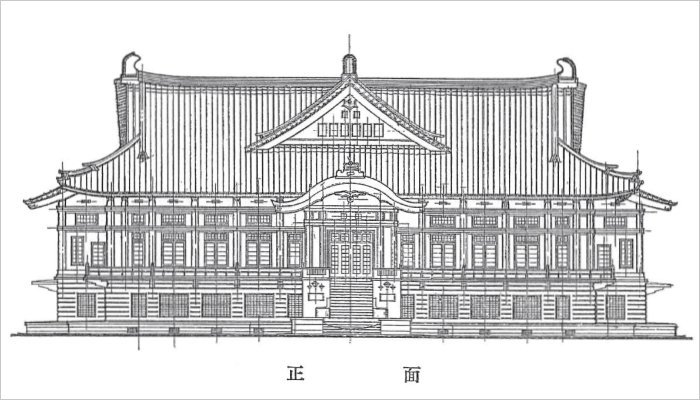

The design of the temple is the part which was the most confusing. The temple was constructed during the Japanese Colonial Era (1895-1945) and to the naked eye seems distinctly "Japanese" in design, but as I recently learned with my blog posts about Taiwan's Butokuden Halls (Longtan, Daxi, Tainan), what we in the west consider to be "traditional" Japanese design is actually heavily influenced by the architecture of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝).

The confusion I experienced while speaking with the lady at the temple was based on this fact.

The temple seems to be of Japanese origin and its inarguable that Japanese architecture and construction methods were used in its construction but they claim that it was designed to imitate a Tang Dynasty building.

There is an argument to be had here - My point of contention on the issue stems from the fact that it would serve a political narrative now that the hall has transitioned from its original purpose as a monastery to that of an ancestral hall to claim that it was of 'Tang' design rather than 'Japanese' - especially if the caretaker who is there most of the time hails from China herself.

I'd like to hear from any of you though - If you know something about Tang Dynasty design and what we consider traditional Japanese architecture, I'd appreciate it if you took a close look at the photos and weighed in with your opinion!

No matter what the design origin of this small hall is, it is quite peaceful and while it hasn't received much care with regards to its preservation, it is one of a few buildings of its kind that remains in Taiwan today making it important historically.

I'm not sure I should recommend people visit this shrine. I'm going to leave a map location to it and if you would like to see it, by all means go check it out - but it's hard to say whether you'll be welcomed or not. It's an interesting place but I think not much is known about it for a reason.

Historically speaking it is a great example of Japanese Colonial Era architecture and construction techniques and I appreciate the fact that there are privately owned shrines like this that are still in existence today.

If you do visit, let me know how your interaction goes with the lady who runs the place!

Location

Gallery / Flickr (High Res Photos)