When foreign streaming services started arriving in Taiwan, a battle started over access to local content, which could be added to their extensive libraries of movies and television shows. With Netflix and Disney+ being the most popular choices for most consumers in Taiwan, both companies sought to add as much Taiwan-made content as they could, while also investing in producing new content as well.

Suffice to say, this resulted in a considerable amount of freshly-made content, which was afforded the financial backing and support of these massive media companies, and more importantly, higher quality production values, which has been a recipe for success. Television shows like Light the Night (華燈初上), Seqalu (斯卡羅) and Detention (返校) are just a few examples of the recent success that the addition of streaming services have helped bring to Taiwan, allowing the country to tell its own stories on an international level.

Link: 別再說韓劇比較好看!10大必看神作開啟台劇新高度,道盡職場辛酸血淚 (風博媒)

One of the other recent additions was the series Gold Leaf (茶金), lauded as the first-ever television show that was filmed entirely in Hoiluk (海陸腔), the most commonly spoken dialect of the Hakka language spoken in Taiwan. A co-production from the Taiwanese government’s Hakka Affairs Council (客家委員會) and the Public Television Service Foundation (公共電視), the twelve-part series focused on the family of entrepreneur Chiang A-hsin (姜阿新), who hailed from the predominately Hakka village of Beipu (北浦鎮) in Hsinchu.

Link: Hakka period drama ‘Gold Leaf’ to air in November (Hakka Affairs Council)

Telling the story of the family’s struggle to stay in business as the Japanese left Taiwan and the Chinese Nationalists took over, the series (is said to have) done an excellent job helping people learn about the booming tea trade during the 1950s, and it’s popularity got domestic tourists to visit places like Beipu Old Street (北浦老街) and the Daxi Tea Factory (大溪老茶產) to experience that history firsthand.

I have to admit though, I haven’t actually watched it..

The family of tea tycoons depicted in the television show, however, is very closely connected to the subject of today’s article, which will tell the story of an abandoned tea factory in the hills of Hsinchu. Having visited the abandoned factory on a few occasions prior to the television show coming out, I had never really made the connection between the two until I started doing a bit of research into the old building.

My personal interest in the tea factory came after my first of many visits to the recently restored Daxi Tea Factory. As I was looking for information about other Japanese-era tea factories around the country, once I found it, I visited a couple of times to get photos.

This however is where I have to add my usual disclaimer regarding my articles on Urban Exploration - In this article, I’ll provide historic information about the tea factory - I’ll even provide it’s name - What I won’t do though is provide readers with any of the other particulars, so if you find yourself so interested that you’d like to check it out on your for yourself, it shouldn’t take very long to figure out where it is.

Before I get into any details about the abandoned tea factory, it’s probably a good idea to start out by introducing talk about the man (and the family), of tea tycoons who owned it - and several others throughout the mountains of Hsinchu - and for whom the television show mentioned above is dedicated.

Chiang A-hsin (姜阿新)

The life of Chiang A-hsin was a long and eventful one, and given that there has been quite a bit recorded about the rise and fall of his family’s tea empire over the years, I’ll try to keep this a brief introduction.

Born in 1901 (明治34年), in what is now Baoshan Village (寶山鄉) in Hsinchu, Chiang A-hsin was adopted as a child by Chiang Qing-han (姜清漢), who was heir to the Beipu Chiang family, and who was described as ‘barren’ or unable to have children of his own.

Little seems to be written on the subject in English, but in Taiwan, it was common (for a variety of reasons) for well-off families to adopt children from families who would otherwise have trouble raising the child on their own. In this case, it was because the Chiang family required a male heir to carry on the family name, but in other cases it could be that the family required a daughter to marry to one of their sons, or for purposes of indentured servitude, etc.

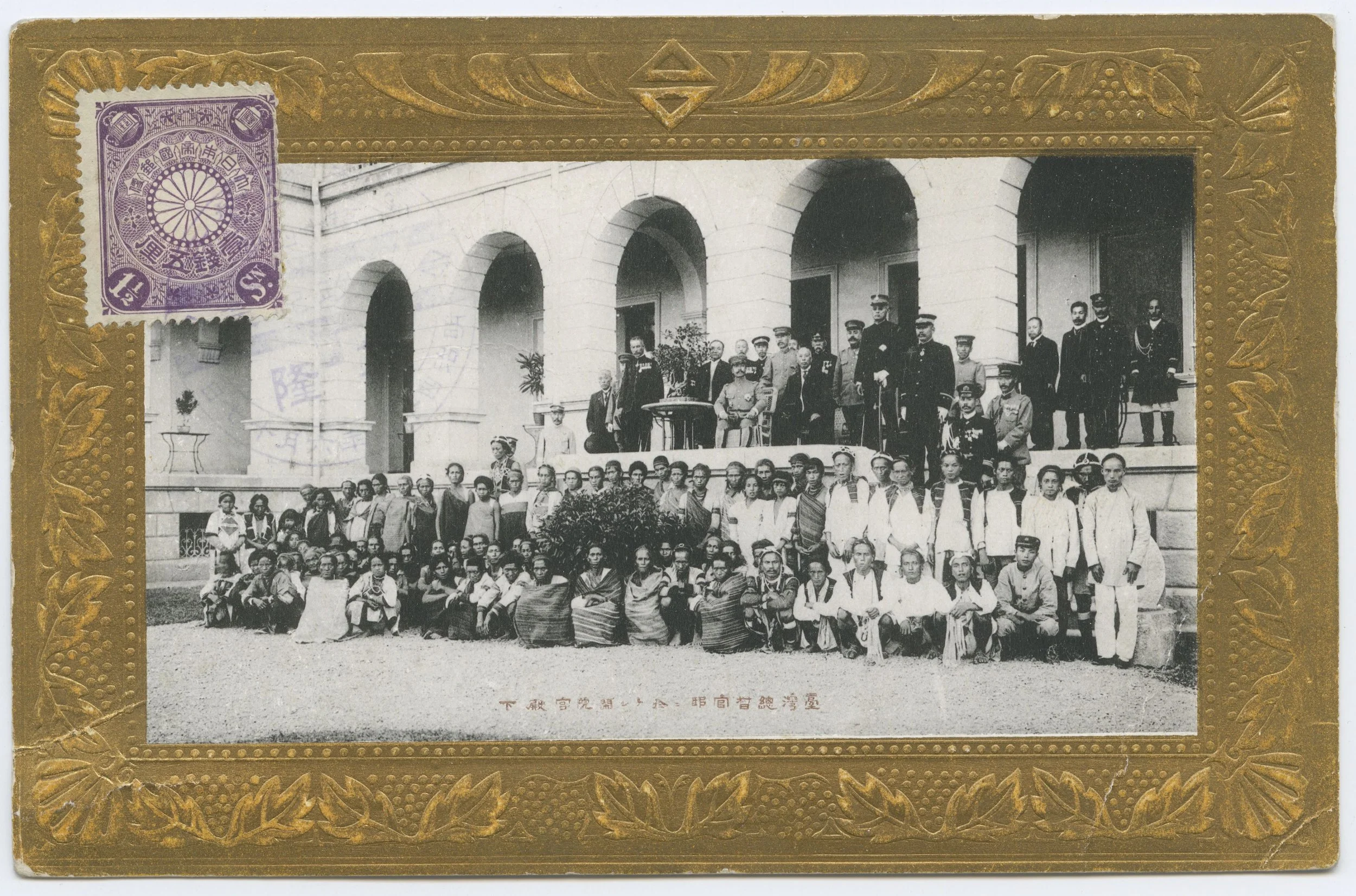

Nevertheless, Chiang A-hsin was adopted and groomed to become the heir of the wealthy Beipu family, who struck it rich during the Qing Dynasty with their Jinguangfu Land Reclamation Company (金廣福墾號). Starting his education at the Beipu Public School (北浦公校), he then moved on to the prestigious Taihoku Kokugo Gakko (臺灣總督府國語學校 / たいわんそうとくふこくごがっこう) at the age of fourteen.

Shortly after his graduation from the college, he traveled to the Japanese mainland, and spent a year reading law at Meiji University (京明治大學) in Tokyo. However, do to pressing family matters back at home, he didn’t end up finishing his degree and instead returned to Taiwan to help out.

Over the next several years, Chiang attempted to invest in or start his own business on several occasions, but each attempt was met with opposition from his father. Chiang then took a job as the assistant to Tanaka Tori (田中利), the head of Hopposhō Village (北埔庄 / ほっぽしょう), known today as Beipu Village. He’d only end up spending two years in the position however as the opposition of his father turned into approval when A-hsin became the head of the family, and proved to his father that he was capable of investing the families wealth responsibly.

Even though his position as assistant to the head of the village might have been short-lived, Chiang used his time in office to familiarize himself with the growing tea manufacturing industry in the village, which was praised for the high-end product that it was producing. Using what he learned and the important networking opportunities that he had, Chiang threw his own hand into the industry by organizing the Beipu Tea Collective (北埔茶葉組合), which grew exponentially over the next few years - starting with the Beipu Tea Farm (北埔茶場) in 1934 (昭和9年), Emei Tea Factory (峨眉茶廠) in 1935 (昭和10年) and then the Hengshan Tea Factory (橫山茶廠), Wufeng Tea Factory (五峰茶廠), and finally the Daping Tea Factory in 1936 (昭和11年).

To give you of an idea of the high-quality nature of the tea that was being produced by Chaing’s Beipu Tea Collective, the tea being produced in the mountains of Hsinchu at the time was sold at a price ten times to typical market price for Oolong Tea at the time. Given the high quality of the tea and the reputation that came with it, Chiang formed partnerships with the Mitsui Agriculture and Forestry Association (三井農林會社), which brought the benefit of having the most modern tea-producing technology available at the time.

However, during the Second World War, the Governor General’s Office in Taipei moved quickly to control certain areas of the economy, especially those with regard to the supply of commodities. The production of tea was an important one for both domestic and international consumption, so the government took control in order to better siphon off the profits, which could be distributed for the war effort.

By 1941 (昭和16年), the “Beipu Tea Collective” was restructured into the Chikuto Tea Company (竹東製茶株式會社). Yet, thanks to his experience in the industry, and his notoriety, Chiang was able to continue as president, maintaining his position and influence within the industry.

After the war, the Chikuto tea Company was dissolved and the ownership of the tea factories was returned to their original owners. By that time, the reputation of Beipu’s tea was pretty solid, specializing in what is known in Hakka as “phong-fûng chhà” (椪風茶) or Oriental Beauty Tea (東方美人茶). In the Hakka language, the name of the tea was essentially “Braggers Tea”, which was used because the producers were ‘so proud of their product that they bragged to everyone’ about how much money they were making from selling it.

Link: Dongfang meiren 東方美人茶 (Wiki)

Shortly after the Chinese Nationalists took control of Taiwan, Chiang renamed the company Yung Kuang Tea Company (永光股份有限公司) and started exporting tea under the Three Star (三星) and Ho-ppo Tea (北埔茶) brands. The success of the global export industry apparently surpassed even that of India’s Darjeeling Tea for a short time, putting Taiwanese tea on the world stage and attracting guests from all over the world to visit Taiwan. With all the foreign tea trading companies visiting Beipu, Chiang decided to build his famous mansion in Beipu where his family lived and received guests.

However, things changed in the 1950s when other tea producing areas around the world, affected by the war resumed production. With its competitive advantage lost, Taiwan’s tea production started to suffer and the relationship between Chiang and his foreign partners suffered.

At wits end, Chiang eventually retired and the company was taken over by his daughter, who attempted to make changes to save the business. Ultimately, the international market, Taiwan’s political situation and the amount of loans proved too difficult to overcome and they were forced to file for bankruptcy in 1965 (民國54年). I don’t want to give you too many spoilers, so if you have the time to watch ‘Gold Leaf’ on Netflix, you’ll be able to see the struggles the family had to go through.

Chiang later moved to Taipei with his family and lived there until his death in 1982. Today, his historic mansion has been restored, and is open in Beipu for tours.

Daping Tea Factory (大平製茶厰)

The Daping Tea Factory (大平製茶厰) opened in June of 1934 (昭和9年) under the official name “Dapingwo Tea Cooperative Factory” (太平窩茶葉組合製茶工場), and was one of the first tea factories in the area that was able to make use of modern technology in the production process.

While the tea factory was officially part of Chiang A-hsin’s ‘Beipu Tea Collective’ mentioned above, throughout its history, it has been managed by a number of different groups of local tea farmers, more specifically after the war, the Hsinpu Liu family (劉氏), one the prominent clans of Hakka residents of the area.

The history of the factory is one that is reminiscent of many of Taiwan’s agricultural industries in that they had to find a way to deal with the transition of political control from the Japanese to the Chinese Nationalists. For the locals, the ability to successfully stay afloat in business during either era was a delicate (and dangerous) balancing act that required a considerable amount of political knowhow. The Beipu Tea Collective under the leadership of Chiang A-hsin, though, was one of the fortunate pieces of Taiwan’s agricultural industry that was able to successfully navigate the transition.

However, as I’ve already pointed out, Taiwan experienced somewhat of a ‘golden era’ of tea production after the war with the support of the Chinese Nationalist regime. When that golden era came to an end, not even endless government subsidies were even able to keep successful businessmen like Chiang A-hsin afloat, and many of the tea factories across the island started to shut down.

Despite the decline in the fortune of the Chiang family, the Daping Tea Factory was able to outlive many of the other tea plantations across the country, and with the cooperation of the government, the owners cultivated several varieties of tea. Transitioning away from Oriental Beauty (東方美人 / 青心大冇) to other types of of tea leaves, they produced popular varieties such as Black Tea (紅茶), Baozhong (包種茶) and Dong-ding (凍頂茶), which continue to be the most common varieties of tea that are cultivated in Taiwan today.

Interestingly, in the post-war period, the cultivation of tea in Taiwan expanded upon some of the experimentation that took place during the Japanese-era, and the result was a number of hybrid species that combined indigenous teas with those more common in India, and other major tea producing countries around the world. The cultivation of these new ‘Taiwan teas’ was streamlined throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and the teas being produced received official classifications based on the experimental process that was used to create them.

Instead of having a bunch of confusing names, the government promoted teas with a number - for example “Taiwan #1” (台茶1號) through “Taiwan #13” (台茶13號), a classification system that remains in place today - and was a beneficial exercise in marketing Taiwanese produced teas to the international market.

In the 1950s, there were over three-hundred tea factories spread throughout Taiwan, a third of them located in Hsinchu. Working together with the other fifteen factories in Hsinpu Village (新埔鎮), the tea produced in the area maintained a high reputation for quite some time, and the success of the export market helped to stabilize a tea industry that was showing signs of decline.

Nevertheless, the decline, which was brought on by international market trends dealt a decisive blow to Taiwan’s tea industry, and even though earnest attempts were made to revive the struggling industry, by 1988 (民國77年), only nine of the original fifteen factories in Hsinpu remained in operation. Less than a decade later, only two of them remained.

By 2013 (民國102年), almost all of the tea factories in the area had been abandoned, with the few remaining converted into tea wholesale businesses.

Unfortunately, information regarding the closure of Daping Tea Factory’s business operations is difficult to find, so I can’t give you an actual date as to when it went out of business, but it’s safe to say that it fell victim to the number of closures that took place between the late 1980s and 1990s.

It’s also difficult to say when the place was abandoned, but given that there was a residence and/or a dormitory within the building, it might have been occupied for a period of time after going out of business.

Recently, the arched wooden roof of one of the buildings collapsed, and out of concern for the local community, the owners of the properly planned to have the building torn down, but the Hsinchu County Bureau of Cultural Affairs (新竹縣政府文化局) stepped in and sought to have the building ‘protected’ for future use, although it is currently unclear as to what that will entail.

One would hope, given the popularity of the television series, as well as the Daxi Tea Factory as a tourist destination, that it’s likely that it might receive some attention sooner rather than later. But that’s up in the air at this point.

Link: 百年大平製茶廠 竹縣爭納古蹟 (自由時報)

Now, let me take a few minutes to detail the architectural design of the building, which even though is in pretty rough shape at the moment, remains quite interesting.

Visiting the factory today, its rather obvious that the original tea factory, constructed during the Japanese-era, was expanded upon several times over the post-war era to meet the needs of a modernizing industry. When we view the factory today, it is essentially split into three different sections - each of which varies with regard to its architectural design and construction methods.

It probably goes without saying that, as far as I’m concerned, the section that remains from the Japanese-era is the most interesting - but taking into consideration that it was constructed primarily constructed of wood in the 1930s, it’s also the part of the factory that is currently in the worst condition.

The original section of the tea factory was actually quite similar to what you can still see at the Daxi Tea Factory in Taoyuan in that it was a two-story brick building, which featured load-bearing walls. In both cases, the top floor was used as a drying area, while the first floor was where the tea was processed.

The roof that covered the drying area was a typical hip-and-gable roof (歇山頂) which was covered with red roof tiles (閩式紅瓦), a type of clay tile which are ubiquitous with traditional Hokkien (閩南) and Hakka (客家) buildings in Taiwan. While the decorative elements of the roof are subdued compared to most other historic buildings in Taiwan, the roof’s fusion of Japanese-style architectural design with that of Hakka elements is an interesting one, but not entirely unique, as you’ll see in the link below.

Starting with the shape of the roof, ‘hip-and-gable’ in this case is better referred to as irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) as it is one of the most common forms of traditional Japanese architectural design, and is used on anything from Buddhist temples and Shinto Shrines to buildings like this one. Roofs in this style tend to vary in the level of decorative elements added, and in this case the decorations are quite subdued.

Nevertheless, this style of architectural design tends to be quite practical given that the ‘hipped’ section provided excellent stability to the base of the building, while the ‘gable’ section ensures the stability of the roof. All of this was accomplished through a genius network of trusses (屋架) located within the ceiling that assists in distributing the weight and support the four-sided sloped hip roof (四坡頂).

If you explore the tea factory today, you can see the original wood used to help stabilize the roof in the section left standing and contrast it with the section that has already caved-in. In the latter, the trusses remain in pretty good shape despite having caved in and being open to the elements for a number of years, which likely points to the fact that they weren’t the cause of the cave in.

As mentioned above, the roof tiles feature as part of the roof’s decorative design, but the fusion of Japanese-style architecture with Taiwanese red roof tiles here tends to play a more functional role than a decorative one. Along the arched section of the roof, you’ll find what appear to be lines of cylindrical roof tiles separated by flat sections of tile that make it seem like ocean waves. The functional nature of the roof tiles placed in this way assist in controlling the flow of rain water.

With the building constructed during the Showa-era, construction techniques in Taiwan had become considerably more refined, so even though the weight of the roof was stabilized by the trusses within the building, the load-bearing brick walls allowed for a number of windows to be placed on all sides of the building to assist in the process of drying the tea leaves. Surrounding the remaining second-floor section of the second floor on three sides, the windows allow for a considerable amount of natural light and in the summer sun, the room tends to shine, making it the most interesting section of the building, photographically.

Located to the rear of the original section of the building you’ll find a post-war addition to the original tea factory. This section, similar to the building in front is a two-story structure, but it also includes a basement where you can still find a considerable amount of the original machinery that was used in the process of tea production. Having all of this historic machinery just sitting there open to the elements is actually quite sad as it is just wasting away in its current condition. The basement of the building tends to be quite damp and muddy, so it’s hard to say that much of anything inside would be of any use other than for display purposes.

Finally, the most recent addition to the tea factory is simply a three-story reinforced concrete building that is typical of post-war design. The building features very little in terms of decorative elements and was never painted.

Essentially it looks like almost every Taiwanese house that was constructed over the past forty or fifty years. Within the interior of the building however you’ll find what was probably the factory’s administrative section as well as an area reserved as the dormitory for the factory’s employees, who were likely migrant laborers.

What is probably the best part of this section of the factory is that you can easily access the roof to get a better view of the caved-in section of the original tea factory, but if you do explore the building, you’ll want to be careful walking around as it could be somewhat dangerous as well.

As mentioned earlier, this article is currently classified as one of my ‘urban exploration’ articles, which means that I won’t be sharing much about the location of the building, or how to gain entry to the building.

I do hope that at some point that I’ll be able to offer readers an update if and when the building is restored and re-opened to the public as a tourist attraction - So here’s to hoping that the popularity of “Gold Leaf” will rub off on local officials in Hsinchu looking to cash in on the renewed interest in Taiwan’s golden age of tea, something which this (and many other) tea factories played a role in.

References

新埔百年大平製茶廠 優先納文資指定登錄程序 (自由時報)

歷史建築 新埔大平製茶廠 (新竹縣政府文化局)

姜阿新 (Wiki)

Chiang A-Hsin Mansion (Hakka Affairs Council)