There is a very short list of buildings in Taiwan that have been able to celebrate their centennial while also continuing to serve the exact same purpose they did when they were first constructed. Next year (2022) however will see that exclusive list grow a little longer with a couple of railway stations that will be celebrating one hundred years of service.

There have been few factors more instrumental to Taiwan’s modern development than the construction of the railway network that circles the country. In fact, if it weren’t for the construction of the railway, it’s highly unlikely that Taiwan would have been able to achieve even a fraction of the prosperity that it has today. For a lot of countries (especially my own), the railway might seem like something of an afterthought, but for Taiwan, the railway has always been the beating-heart of the community.

That being said, Taiwan’s rapid and continual development over the past century has also meant that much of its older infrastructure has had to be replaced due to age, and the inability to serve the needs of the modern nation state. Indeed, for most people, efficiency is one of the most important factors in our modern lives, and that means that many of the country’s ‘outdated’ buildings have been left to rot, or have sadly been completely demolished in order to make way for modernity.

As the nation has grown into its own however, people have started to reflect on their heritage while also yearning for increased accessibility to important pieces of their history. In recent years we have seen a renewed focus on the restoration of historic buildings across with the country, and when it comes to the history of the all-important railway, we are blessed with a number of historic buildings and museums where we can learn about the history of this beautiful country.

There are some cases however where we can experience living history, so when we’re able to come across a railway station that has continued to serve the same community for more than a hundred years, it’s a pretty special experience.

Today, I’ll be introducing one of the stations that is regarded as one of the “Coastal Five Treasures” (海線五寶), or the “Coastal Three Treasures” (海線三寶), depending on who you ask. To explain, each of these “treasures” refers to a nearly century-old Japanese-era train station located in either Miaoli (苗栗縣) or Taichung (台中縣) on the coastal section of the Western Trunk Line (縱貫線) of the railway between Keelung and Kaohsiung.

The reason why I saw the name depends on who you ask is due to special situation Miaoli finds itself in as of late with the running joke that it is actually a sovereign country within Taiwan known as Miaoli-kuo (苗栗國). I’m sure someone could write an entire thesis on this running joke and how it originated, but what I’ll say is that in Chinese, the term “Three Treasures” (三寶) is a much more auspicious and meaningful number than five, so linguistically it has more sway. But if you’re not from Miaoli, you might just want to include the two stations in Taichung, because they deserve the same amount of respect.

Note: “Three Treasures” (三寶) linguistically refers to “the Buddha”, “the Dharma”, and “the Sangha” (佛寶, 法寶, 僧寶) in Buddhism, also known as the “Three Jewels” or the “Three Roots” and is a term that has significant meaning throughout Asia.

That being said, the term “三寶” (sān bǎo) has taken on a number of meanings ranging from Hong Kong style of bento box that features three kinds of meat (三寶飯), or an idiot driving on the road (馬路三寶), among others.

This article is the first of a series of posts about these five so-called “treasures,” and I’m going to start by introducing Northern Miaoli’s Dashan Station (大山火車站), which is (out of the five), arguably in the best shape of the lot and is home to a few unique additions that you won’t find anywhere else in Taiwan.

Before I start though, I’m going to take a few minutes to introduce the historic Coastal Railway Line where these stations make their home.

Coastal Railway (海岸線 / かいがんせん)

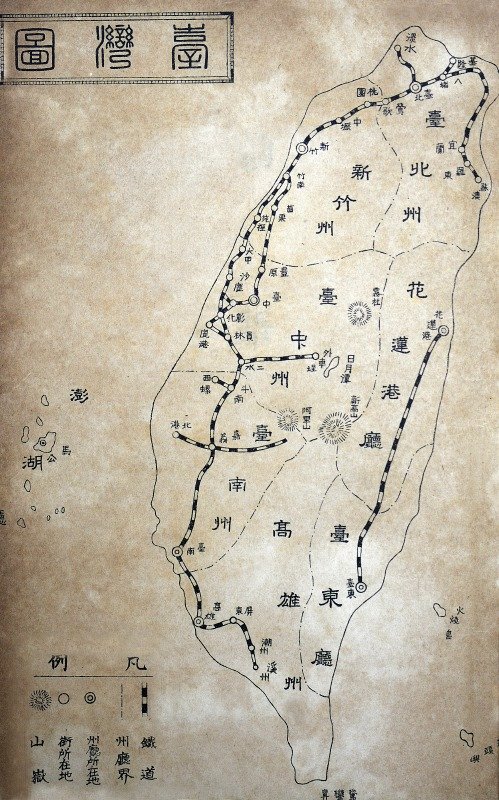

The history of the railway in Taiwan dates back as far as 1891 (光緒17), when the Qing governor, attempted to construct a route stretching from Keelung (基隆) all the way to Hsinchu (新竹). Ultimately though, the construction of the railway came at too high of a cost, especially with war raging back home in China, so any plans to expand it further were put on hold.

A few short years later in 1895 (明治28), the Japanese took control of Taiwan, and brought with them a team of skilled engineers who were tasked with coming up with plans to have that already established railway evaluated and then to come up with suggestions to extend it all the way to the south of Taiwan and beyond.

The Jūkan Tetsudō Project (ゅうかんてつどう / 縱貫鐵道), otherwise known as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project’ sought to have the railroad pass through all of Taiwan’s already established settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄).

Completed in 1908 (明治41), the more than four-hundred kilometer railway connected the north to the south for the first time ever, and was all part of the Japanese Colonial Government’s master plan to ensure that Taiwan’s precious natural resources would be able to flow smoothy out of the ports in Northern, Central, and Southern Taiwan.

Once completed, the Railway Department of the Governor General of Taiwan (台灣總督府交通局鐵道部) set its sights on constructing branch lines across the country as well as expanding the railway network with a line on the eastern coast as well.

However, after almost a decade of service, unforeseen circumstances in central Taiwan necessitated changes in the way that the western railway was operated, with issues arising due to typhoon and earthquake damage. More specifically, the western trunk railway in Southern Miaoli passed through the mountains and required somewhat of a steep incline in sections before eventually crossing bridges across the Da’an (大安溪) and Da’jia Rivers (大甲溪), which started to create a lot of congestion, and periodic service outages when the railway and the bridges had to be repaired.

Link: Long-Teng Bridge (龍騰斷橋)

To solve this problem, the team of railway engineers suggested the construction of the Kaigan-sen (かいがんせん / 海岸線), or the Coastal Railway Branch line between Chikunangai (ちくなんがい / 竹南街) and Shoka (しょうかちょう / 彰化廳), or what we refer to today as Chunan and Changhua.

Link: Western Trunk Line | 縱貫線 (Wiki)

Construction on the ninety kilometer Coastal Line started in 1919, and amazingly was completed just a few short years later in 1922 (大正11), servicing eighteen stations, some of which (as I mentioned above) continue to remain in service today.

Those stations were: Zhunan (竹南), Tanwen (談文湖), Dashan (大山), Houlong (後龍), Longgang (公司寮), Baishatun (白沙墩), Xinpu (新埔), Tongxiao (吞霄), Yuanli (苑裡), Rinan (日南), Dajia (大甲), Taichung Port (甲南), Qingshui (清水), Shalu (沙轆), Longjing (龍井), Dadu (大肚), Zhuifen (追分) and Changhua (彰化).

(Note: English is current name / Chinese is the original Japanese-era station name)

Oyamagashi Railway Station (大山腳驛 / おうやまあしえき)

One of the first things most people notice when stepping off the train onto the platform at Dashan Station is that there aren’t actually any mountains nearby. For those of you who aren’t Mandarin speakers, the name “Dashan” (大山 / dà shān), quite literally translates into English as “Big Mountain,” so you may understand the confusion as to how the station derives its name.

To figure this out, I had to do quite a bit of digging as there isn’t very much information about this station, or the community around it available save for the basics. To start, the original Japanese name of the station was Oyamagashi Station (大山腳驛 / おうやまあしえき), which is slightly different than the current name. The difference is that there is an additional Chinese character “腳” (jiao), which means “foot” or “base” and could be interpreted as the area at the base of a large mountain.

Still though, there aren’t any large mountains nearby, so we have to dig a bit deeper.

It turns out that the Hokkien people (閩南人) who had settled in the area long before the arrival of the Japanese referred to sections of their community either as the ‘upper’ (上大山腳) or ‘lower’ (下大山腳) base of the mountain, or ‘hill’ in Taiwanese as “Suann-lūn” (山崙). In this case instead of an actual ‘mountain’, the word refers to a small hill that is elevated higher than the general terrain. In this way, you could argue that this is a fitting description as the station is located at a lower elevation than the rest of the community that it serves with hills and sand dunes on the opposite side near the coast.

As mentioned above, the Coastal Line was completed in 1919, but these smaller stations didn’t actually start appearing until a few years later. This was due to the fact that the purpose of the line wasn’t originally meant to provide passenger service, but to ease the congestion of freight traffic between the north and south through that dangerous patch of railway in central Taiwan. So when these stations started appearing, they were actually meant for driving economic development with relation to moving freight and the products from the coastal areas.

And if you know anything about the Houlong (後龍) area, that freight was most certainly copious amounts of watermelons being sent to port in Taichung for export back to Japan. If you weren’t already aware, Taiwanese fruit exports were huge during the Japanese-era, and watermelon and pineapples were especially popular.

Oyamagashi Station as we know it today was constructed in 1922 (大正11年) and officially opened for passenger service on October 10th, which is actually a pretty cool coincidence as I started writing this article on October 10th, 2021, the 99th anniversary of the station.

Before I get into the architectural design of the station, I’ll provide a bit of a timeline of events that took place at the station over the past century.

10/11/1922 - The station opens for service and is named Oyamagashi Station (大山腳驛)

10/25/1945 - The Japanese formally surrender control of Taiwan at the end of WWII.

04/01/1965 - The station is officially renamed “Dashan Station” (大山火車站).

04/01/1991 - The station is reclassified as a ‘Simple Platform Station’ (簡易站).

06/10/2005 - The station is recognized as a protected historic building (歷史建築).

06/30/2015 - The station switches to the usage of card swiping services rather than issuing tickets.

12/23/2019 - A drunk driver crashes his truck into the front of the station causing considerable damage.

10/10/2022 - The station will celebrate its 100th year of service.

To expand on a few of the points above, many of the coastal line’s stations were converted to ‘Simple Platform Stations’ in the early 1990s, which essentially meant that they would only be serviced by Local Commuter Trains (區間車), while the express trains would pass by without stopping. It also meant that the station wouldn’t continue to have a Station Manager (站長) on site with those responsibilities delegated to the manager of a larger station nearby, in this case, Houlong Railway Station (後龍火車站).

Architectural Design

Interestingly, when we talk about the stations that make up Miaoli’s Japanese-era “Three Treasures”, the architectural design of each of the stations differ only in slight ways. I suppose this shouldn’t be too much of a surprise given that they were all smaller stations, each of which opened in 1922, meaning that they obviously saved some money when it came to architectural design. That being said, the design of these buildings is about as formulaic as you’ll get with Japanese architectural design, but don’t let that fool you - the simplicity of these stations allows for some special design elements.

The station was constructed in a fusion of Japanese and Western architectural design, and one of the reasons it stands out today (apart from its age) is that it was built almost entirely of wood (木造結構), more specifically locally sourced Taiwanese cedar (杉木), making use of a concrete base and a network of beams within the building to ensure structural stability.

The architectural design fusion of the stations that were constructed during the Taishō era (大正) often borrowed elements of Western Baroque (巴洛克建築) and combined them with that of traditional Japanese design. In this case, the design is quite subdued (likely for cost saving measures), which makes the traditional Japanese design elements stand out more. That being said, even though the architectural design is considered simplistic in comparison to other Japanese-era buildings, it does feature several elements that allow it to stand out.

To start, the station was constructed using Irimoya-zukuri (入母屋造 / いりもやづくり) style of design, most often referred to in English as the “East Asian hip-and-gable roof.” As mentioned above, the building was constructed with a network of beams and trusses found in the interior and exterior of the building. This allows the roof to (in this case slightly) eclipse the base (母屋) in size and ensure that its weight is evenly distributed so that the building doesn’t collapse.

The roof itself was designed using the kirizuma-zukuri (妻造的樣式) style, which is one of the oldest and most commonly used designs in Japan. Translated simply as a “cut-out gable” roof, the kirizuma-style is one of the simplest of Japan’s ‘hip-and-gable’ roofs. What this basically means is that you have a section of the roof (above the rear entrance) that ‘cuts’ out from the rest of the roof and faces outward like an open book (入), while the longer part of the roof is curved facing in the opposite direction. From the front of the building, the roof looks rather simple save for the fact that it is split into two levels with a lower section that covers the walkway that surrounds the building on three sides.

The roof is covered in Japanese-style black tiles (日式黑瓦), which were replaced in 2000 (民國89年) after almost eighty years. Still, after twenty years the current roof tiles are in pretty good shape despite their color fading somewhat thanks to the salt in the air due to the proximity to the coast.

The area between the upper part of the roof and the lower part features several glass windows meant to allow for natural light to enter the building. Unfortunately, at some point someone had a brain fart and placed square lighted signs with the name of the station that blocks the windows. This is one reason why you’ll find that the interior of the building is a little dark, even during the afternoon when the sun is at its brightest.

The interior of the building is split in two sections, much like what we saw the former Qidu Railway Station with the largest section acting as the station hall while the other was where the station staff and ticket windows were located. Given that this station is still in operation, only one side is understandably open to the public. That being said, there’s not really a whole lot to see when you’re inside as there is only a ticket counter and a passageway to the platform area. The floor is made of concrete, and it looks like it has seen better days. There are large sliding glass windows next to the front entrance as well as to the right while there is a wall on the other side where you’ll find the ticket booth.

Link: Xiangshan Station (香山車站)

One of the most notable aspects of the interior is the wooden gate located near the ticket booth. The gate is rather unique in Taiwan these days in that it is constructed to look like the Japanese word for ‘money’ (円). Likewise, once you’ve passed through the building to the other side you’ll find a beautiful wooden barrier that is similarly one of a kind in Taiwan these days.

From the rear, one of the most notable baroque-inspired elements is the round ox-eye window (牛眼窗) located above the cut section of the roof near the arch. This window helps to provide natural light into the office section of the building, and is one of those architectural elements that Japanese architects of the period absolutely loved.

Before I finish, one of the events mentioned above in the timeline ended up changing (or disfiguring if you prefer) the face of the station. Unfortunately the news was only reported in Chinese, so I’ll summarize in English here: In 2019, a drunk driver passing through the community lost control of his blue truck and crashed directly into the building, causing a considerable amount of damage. There isn’t a lot of information about the station currently available online, but when you do search it, almost all of the results you’ll get are related to this unfortunate event. The accident caused some problems for the station, but given that it was a protected historic property, the Taiwan Railway Administration did their best to have it fixed as best they could. When you look at the front of the station now though, you’re likely to notice that there are some wooden panels that are a different shade than the others, and this is why.

Whether or not this was an accident, or intentional is hard to tell. There are certain people in Taiwan who would prefer to see all of the Japanese-era buildings destroyed, hoping to see that part of Taiwan’s history erased from existence.

If you click the link below you’ll see some of the photos from the incident.

Link: 貨車駕駛酒駕闖大禍 撞毀百年歷史建築大山車站 (CNA)

Getting There

Address: #180 Mingshan Road. Houlong Township, Miaoli County (苗栗縣後龍鎮大山里明山路180號)

GPS: 24.645670, 120.803770

As is the case with any of my articles about Taiwan’s historic railway stations, I’m going to say something that shouldn’t really surprise you - When you ask what is the best way to get to the train station, the answer should be pretty obvious: Take the train!

Dashan Railway Station is one of the first stations you’ll reach in Miaoli County while traveling south on the Western Coastal Line (海線), so when you think about it, it’s not actually that far away from Taipei, or anywhere in Northern Taiwan. Taking only half an hour from Hsinchu Railway Station (新竹火車站), you’ll be able to check out the station at your leisure before hopping back on the train to your next destination.

That being said, if you’re already in the area and have access to a car or a scooter, you can easily find the station if you input the address provided above into your GPS or Google Maps. The station is located within Miaoli’s Houlong Township (後龍鎮) along the west coast highway. If you’re driving a car, you’ll find that the station is a simple turn off of the highway into a quiet little village, where you’ll find very little traffic and even fewer people.

When you arrive at the station, you should be free to walk around and check it out, but if the volunteer who works there is in a bad mood (not likely) you might have to purchase a ‘platform ticket’ (月票 or 月台票) which will allow you to enter the station and walk through the turnstile without getting on the train. It’s the kind of thing people used to purchase when they were seeing off their friends or family, and should only cost about 10NT. You could also just swipe your EasyCard to go in and out, but that’ll cost more (the base price for swiping the card is higher) if you aren’t traveling on the train.

For a lot of people, a simple day-trip could might revolve around a trip to either three, of if ambitious enough, five of the “treasures” which allows you to visit each of these still functioning Japanese era stations. There are a lot of things you can do while hanging out in Taiwan, and while it might seem pretty random to visit five train stations in a single day, it is actually an enriching experience.

I’m not saying that is what you should do, but if you are so inclined, I would applaud anyone who tries it. If you find yourself in Miaoli (especially along the coast) and you’re looking for something to do, I recommend stopping by at least one of these stations to experience a bit of living history.

References

Dashan Railway Station | 大山車站 (Wiki)

大山腳 (苗栗縣) (Wiki)

海線五寶 (Wiki)

大山車站 (Miaoli Travel)

大山車站 (TRS TOUR)

大山火車站 (國家文化資產網)

苗栗-百年木造車站/大山車站 (珍珍的窩)

海線的老火車站 (一): 大山火車站 (Maggie’s Home)

細說苗栗「海線三寶」車站物語 (臺灣故事)

木造車站-海線五寶 (張誌恩 / 許正諱)

海線僅存五座木造車站:談文、大山、新埔、日南、追分全收錄!(David Win)

大山車站‧木造老車站的旅行即景 (journey.tw)