Over the past year or so, I’ve found myself spending a considerable amount of time researching the history of the railroad in Taiwan. Obviously, much of the rail network that we know and love today is primarily a result of the fifty-year Japanese Colonial Era, so as part of my evolving research and personal interest in that period of Taiwan’s history, I've been traveling around the country taking photos of a collection of century old stations.

That being said, over much of that time, I’ve been focused primarily on a specific group of stations known locally as the ‘Five Treasures of the Coastal Railway’ (海岸線五寶), with the lingering thought in the back of my mind that there are still dozens of others around the country that I’ll eventually have to visit.

When it comes to these things, I tend to be a pretty organized person, so while writing about the Five Treasures, I came to the conclusion (mostly for my own research purposes) that I should compile a list of all of those stations. In this way, I could better allocate my time and ensure that whenever I travel, I’m able to use my time more wisely.

While compiling the list however, I ended up discovering that there are very few authoritative resources that focus on these historic stations, or any that offer a complete list of what actually remains standing today.

To solve this problem, I dove deep into that rabbit hole and compiled a comprehensive list of over sixty historic Japanese-era stations that continue to exist in some form today. The final result is a list that is divided into various sections based on the branch of the railway where you’ll find them, including stations that belong to the historic sugar and forestry lines. Moreover it offers information as to their current operational status as well as their original Japanese-era names. I’ve also added a list of other railway-related sites, including the three former Railway Bureau Offices (鐵道部) in addition to any railway hospital, dormitory, tunnel or railway-related place of interest that has been restored in recent years.

That being said, I still consider these lists to be a work in progress, and I’m sure that despite my best efforts, I’ve missed something, which will have to be added in the future.

So, if you are aware of a station or important Japanese-era railway site that I’ve yet to add to the list, I’d be more than happy for your feedback as I hope to see the list continue to evolve over time.

Similarly, as I continue to write new articles about these historic stations, I’ll continue to update links.

You might ask why I feel that these stations are important - they’re just train stations, right?

Well, given Taiwan’s complicated history of colonial powers exerting control over the island, there has been an unfortunate erasure of history with each successive regime. Coupled with modern development having little-to-no regard for the nation’s history, a large percentage of what we could consider heritage sites across the country have been lost. Sure, we can easily find places of worship that are several hundred years old, but almost everything else has been torn down at some point in time.

As I’ve already mentioned, the list I’m providing below features some century-old stations that continue to remain in service today in addition to others that have become historic tourist attractions.

With a total of around two-hundred train stations across the country, many of the originals have already been replaced, making those that remain part of a special group of ‘living’ historic sites, worthy of cultural preservation.

Westerners might not consider a century-old building all that significant, but given Taiwan’s chaotic experience over the past two hundred years, any building that has been able to survive for so long deserves some respect. Likewise, it’s important to note that the introduction of an island-wide public transportation network was essentially a game changing moment in the development and industrialization of the island.

The railway not only brought modernity and economic opportunity, but also contributed to cultural and social change with railway stations acting as the beating heart of the modern Taiwanese town or city. Suffice to say, the ‘local railway station’ is often romanticized by many in Taiwan who have fond memories growing up with the trains becoming an essential part of their lives.

As I move on below, I’ll provide a brief introduction to the history of the Japanese-era railway, then I’ll present the lists as well as a map where you’ll find each of the stations.

I hope this list will be of some use to you, but given that I’ve spent a considerable amount of my free time putting it together, and translating all of the names, I hope it won’t just be copied and stolen without contacting me to ask for permission.

Taiwan’s Japanese-era Railway (臺灣日治時期鐵路)

The history of Taiwan’s railway network dates as far back as the late stages of the Qing Dynasty when a rudimentary railway was constructed between Keelung and Taipei in the 1890s, with plans to further expand the line all the way to the south. For many, one of the biggest misconceptions of ‘Chinese’ rule here in Taiwan is that they controlled the entire island. They didn’t, and had little aspiration to expand beyond the pockets of the western coast of the island that they did control.

So when the short-lived First Sino-Japanese War (日清戰爭) broke out in 1894, plans for further expansion of the railway were ultimately abandoned due to a lack of funds, and a lack of interest in the island’s development.

When the Japanese ultimately won that war, one of their demands was that the Qing cede the island of Taiwan (and the Pescadores) to the Japanese empire, which was quickly approved given that many back then considered the island a useless piece of untamed land, full of hostile indigenous peoples.

The Japanese on the other hand saw potential as the island was a massive cache of natural resources. So, in 1895 the Japanese showed up, and quickly got to work on plans to construct a railway network that would allow them to efficiently develop the island for the extraction of its precious natural resources.

Nearing the end of 1895 (明治28年), the colonial regime stationed a group of military engineers known as the ‘Temporary Taiwan Railway Team’ (臨時臺灣鐵道隊) in the northern port city of Keelung to carry out repairs on the existing railway, conduct surveys, and to come up with plans for improvements. Within a year proposals were drawn up to completely re-route the existing rail line from Keelung to Taipei in another direction for better efficiency, and a more ambitious plan known as the Jūkan Tetsudo Project (ゅうかんてつどう / 縱貫鐵道) was born.

Known in English as the ‘Taiwan Trunk Railway Project,’ the planning team sought to have the railroad pass through all of Taiwan’s already established settlements, including Kirin (基隆), Taihoku (臺北), Shinchiku (新竹), Taichu (臺中), Tainan (臺南) and Takao (高雄), a more than four-hundred kilometer railway.

Completed in 1908 (明治41), the railway connected the north to the south for the first time ever, and was all part of the colonial government’s master plan to ensure that natural resources would be able to flow smoothy out of the ports in Northern, Central, and Southern Taiwan.

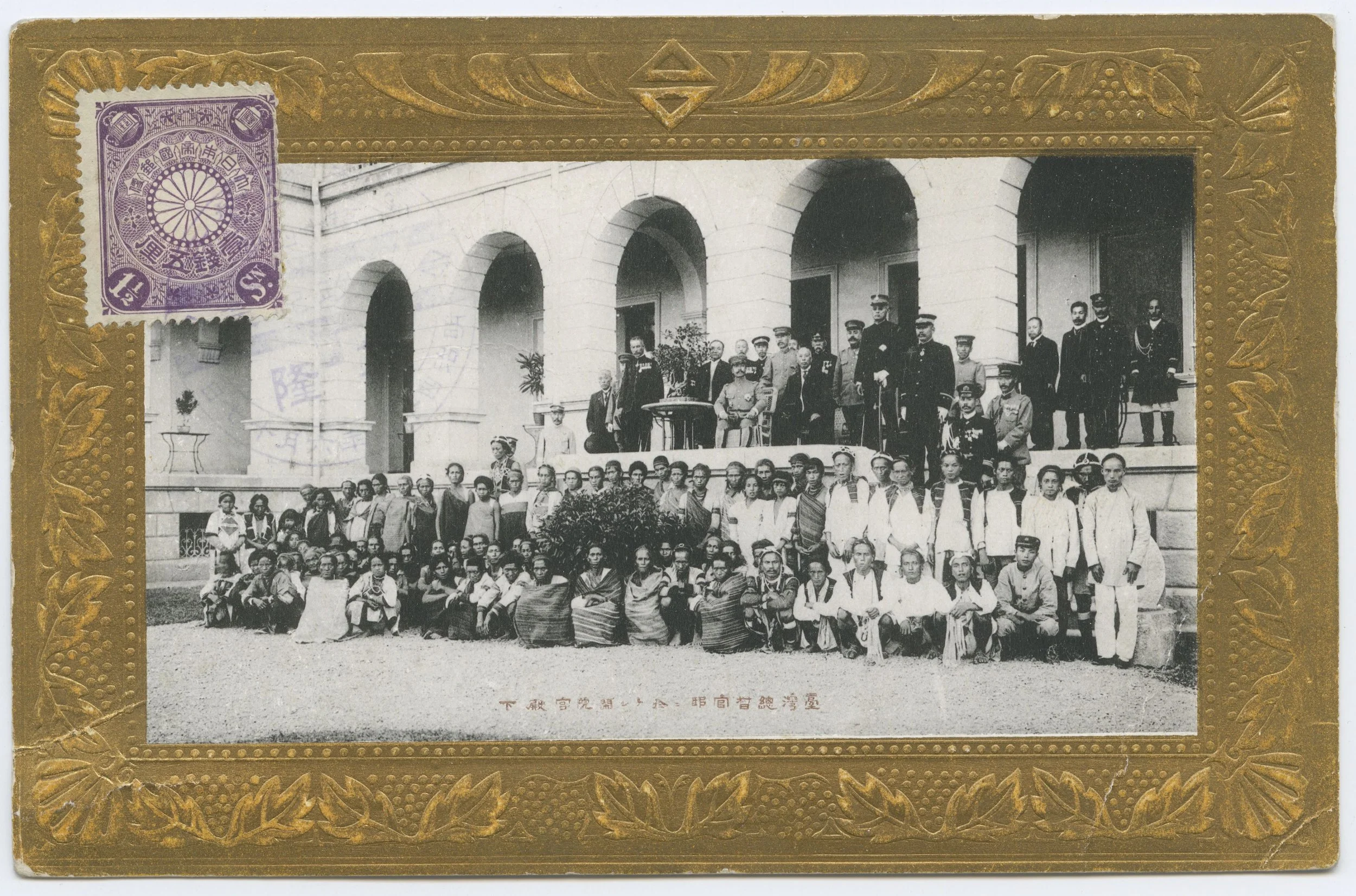

Then, the Railway Department of the Governor General of Taiwan (台灣總督府交通局鐵道部) set its sights on constructing branch lines across the island in addition to expanding the railway along the eastern coast.

Looking at a map of the railway network today, one thing you’ll notice is that the lines appear to completely encircle the island. From the 1910s until 1945 (and in some cases longer), the network appeared more like an intricate spiderweb of lines with industrial branch lines scattered across the island.

As the railway continued to expand across the island, cities and economic opportunity followed, but with limited space, there is only so much that they could construct. Thus, the fifty year period of Japanese colonial rule is often split into two different periods by historians - The period between 1895 (明治31年) and 1926 (昭和元年) is referred to as the period of major railway construction while 1927 (昭和2年) to 1945 (昭和20年) is regarded as the period of railway improvement.

The vast majority of the railway network’s stations were constructed during the Meiji Era (明治) from the time that Japan took control of Taiwan until 1911. The Taisho (大正) and Showa (昭和) eras then saw continued expansion of the railway, but for the most part many of the rudimentary stations constructed in the early years of the colonial era were replaced or reconstructed, with many of the stations that we can still see today (on the list below).

There are several factors as to why authorities at the time sought to improve the infrastructure network, but I suppose the most obvious was due to the wear and tear caused by natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons, which so commonly take place here in Taiwan. The modern construction techniques and materials introduced during the Taisho era meant that instead of constructing buildings purely of timber, reinforced concrete could then be utilized to ensure a longer life for many of the island’s important buildings.

It was also during this time that the railway network was improved with new bridges, tunnels and train engines all working together to improve the efficiency of the network.

Ultimately, the colonial era came to a conclusion at the end of the Second World War and in the seven decades since, Taiwan’s railway (and public transportation network) has continued to grow with the railway finally encircling the entire island. In recent decades we have also seen the widening of tracks and the electrification of the system. Today, the railway in Taiwan is a well-oiled and efficient machine that is of benefit to every one of the twenty-three million people living in the country and works seamlessly with the High Speed Rail as well as the underground subway networks in Taipei, Taichung and Kaohsiung.

Some pretty horrific things took place during the Japanese era, but it goes without saying that this country wouldn’t be the amazing place it is today if it weren’t for the introduction of the railway.

Now that I’ve said my piece, let's move on to the list of remaining Japanese-era stations.

Taiwan’s Main Lines (營運路線)

Taiwan’s Main Branch Lines, namely those constructed for both passenger and freight services currently consist of three main sections: the Western Trunk Line (西部幹線), the Eastern Trunk Line (東部幹線) and the South-link Line (南迴線). All three of which were planned for construction during the colonial era, yet only the western and eastern lines were completed before the end of the Second World War.

It would take until 1991 for the South-Link Line to finally connect the eastern and western lines, allowing the railway to finally encircle the entire country.

There are of course a number of factors involved, but it’s important to note that the majority of stations on the list below are located primarily along Taiwan’s western coast. The Western Trunk Line running between Keelung and Kaohsiung was completed within a decade of the Japanese taking control of Taiwan, while the construction of the eastern coast railway took a little longer.

The eastern coast of the country is prone to earthquakes, and is affected much more by typhoons than the rest of Taiwan, so it’s understandable that many of those historic stations have been lost over time. It’s also important to keep in mind that the western side of the island has experienced considerably more development than the east, so the number of historic railway stations vastly outnumbers what you’ll find along the eastern coast.

The list of stations below is organized from north to south and ends on the east coast:

-

Qidu Station (七堵車站 / Shichito / しちとえき) - Still in operation (moved)

Huashan Station (華山貨運站 / Kabayama / かばやまえき) Not in operation

Shanjia Station (山佳車站 / Yamakogashi / さんかえき) - Still in operation (moved)

Hsinchu Station (新竹車站 / Shinchiku / しんちくえき) - Still in operation

Xiangshan Station (香山車站 / Kozan / こうざんえき) - Still in operation

Tanwen Station (談文車站 / Tanbunmizumi / だんぶんみずうみえき) - Still in operation

Dashan Station (大山車站/ Oyamagashi / おうやまあしえき) - Still in operation

Hsinpu Station (新埔車站 / Shin-ho / しんほえき) - Still in operation

Shenhsing Station (勝興車站 / Jurokufun / じゅうろくふんえき ) - Not in operation

Rinan Station (日南車站 / Oyamagashi / おうやま あしえき) - Still in operation

Qingshui Station (清水車站 / Kiyomizu / きよみずえき) - Still in operation

Chuifen Station (追分車站 / Oikawe / おいわけえき) - Still in operation

Zaoqiao Station (造橋車站 / Zokyo / ぞうきょうえき) - Still in operation

Tongluo Station (銅鑼車站 / Dora / どうらえき) - Still in operation

Tai-an Station (舊泰安車站 / Taian / たいあんえき) - Still in operation (moved)

Taichung Station (台中車站 / Taichu / たいちゆうえき) - Still in operation (moved)

Ershui Station (二水車站 / Nisui / にすいえき) - Still in operation

Dounan Station (斗南車站 / Tonan / となんえき) - Still in operation

Chiayi Station (嘉義車站 / Kagi / かぎえき) - Still in operation

Shiliu Station (石榴車站 / Sekiryu / せきりゅうえき) - Still in operation

Nanjing Station (南靖車站 / 水上駅 / Mizukami / みずかみえき) - Still in operation

Houbi Station (後壁車站 / Koheki / こうへきえき) - Still in operation

Linfengying Station (林鳳營車站 / Rinhoei / りんほうえいえき) - Still in operation

Tainan Station (台南車站 / Tainan / たいなんえき) - Still in operation

South Tainan Station (南台南車站 Shikenshozen / しげんしやうまへ) - Not in operation

Bao-an Station (保安車站 / 車路墘駅 / Sharoken / しゃろけんえき) - Still in operation

Luzhu Station (路竹車站 / Rochiku / ろちくえき) - Still in operation

Qiaotou Station (橋頭車站 / 橋子頭駅 / Hashikotou / はしことうえき) - Still in operation

Kaohsiung Station (舊高雄車站 / Takao / たかおえき) - Not in operation

Sankuaicuo Station (三塊厝車站 / Sankaiseki / さんかいせき) - Still in operation (moved)

Chutian Station (竹田車站 / Takeda / ちくでんえき) - Still in operation

Guanshan Station (關山車站 / Kanzan / かんざんえき) - Still in operation (moved)

Bin-lang Station (檳榔車站 / Hinashiki Teijajō / ひなしきていしゃじょう) - Not in operation

Branch Lines (產業鐵路)

Most are surprised to learn that the railway that we know today is actually exponentially smaller than the railway of the Japanese era, which was home to dozens of branches off of the main lines.

Connecting important industries to the main transportation network, today, only a few of these branches remain in service. Most notably, the Pingxi Line (平溪線), Neiwan Line (內灣線), Jiji Line (集集線), and the Alishan Line (阿里山線). For the most part, these branch lines weren’t originally constructed with passenger service in mind, they were primarily used for transporting freight and commodities from their point of origin to the main lines so that they could be brought to port.

The most prominent of these branch lines were the ‘Forestry Lines’ (林業鐵路) and the ‘Sugar Lines’ (糖業鐵路), which were constructed to haul sugarcane and timber, while also providing limited passenger services.

Today, a few of the original stations along those historic lines continue to exist, but for the most part service on these lines have been relegated as tourist attractions as the majority of those rail networks have been removed.

Of those branch lines that continue to provide (limited) service today you’ll find the following:

Sugar: the Magongcuo Line (馬公厝線), the Xihu Line (溪湖線), the Zhecheng Line (蔗埕線), the Baweng Line (八翁嫌), the Xingang East Line (新港東線) and the Qiaotou Line (橋頭線).

Forestry: the Alishan Forest Railway (阿里山森林鐵路), Taiping Mountain Forest Railway (太平山森林鐵道), the Luodong Forest Railway (羅東森林鐵路) and the Wulai Scenic Train (烏來台車).

To offer an idea of the scale of the Japanese-era railway, the network in Taiwan today is measured at 2,025 kilometers in length while the Japanese-era the branch railways would have tripled that total length with the Sugar Railways alone spanning 2,900km in central and southern Taiwan.

Below you’ll find some of those stations that continue to exist in some form:

-

Jing-tong Station (青銅車站 / 菁桐坑驛 / Seito / せいとうえき) - Still in operation

Xinbeitou Station (新北投車站 / Shinhokuto / しんほくとうえき) - Not in operation

Hexing Station (合興車站) - Still in operation (Completed in 1950)

Kanglang Station (槺榔驛 / Kanran / かんらんえき) - Not in operation

Xihu Station (溪湖車站 / Keiko / けいこえき) - Not in operation

Lukang Station (鹿港車站 / Rokko / ろっこうえき) - Not in operation

Jiji Station (集集車站 / Shushu / しゅうしゅうえき) - Still in operation

Checheng Station (車程車站 / 外車埕驛 / Gaishatei / がいしゃていえき) - Still in operation

Huwei Station (虎尾車站 / Kobi / こびえき) - Not in operation

Suantou Station (蒜頭車站 / Santo / さんとうえき) - Not in operation

Wushulin Station (烏樹林車站 / Ujiyurin / うじゅりんえき) - Not in operation

Yanshui Station (鹽水車站 / Ensui / えんすいえき) - Not in operation

Qishan Station (旗山車站 / Kisan / きさんえき) - Not in operation

Zhulin Station (竹林車站 / Chikurin / ちくりんえき) - Not in operation

Dazhou Station (大洲車站 / Daishu / だいしゅうえき) - Not in operation

Tiansongpi Station (天送埤車站 / Tensohi / てんそうひえき) - Not in operation

Historic Morisaka Station (萬榮工作站 / Morisaka / もりさかえき) - Not in operation

Alishan Forest Railway Branch Line (阿里山林業鐵路)

One of the Colonial Government’s most ambitious railway construction projects was the Alishan Forestry Branch line, which was constructed to more efficiently transport one of the era’s hottest commodities, Taiwanese cypress (hinoki / ひのき / 檜木).

The branch line has remained in operation for almost a century now, and despite a few setbacks, it remains a popular tourist excursion out of Chiayi. Below, I’m listing some of the Japanese-era stations that remain in operation along the line today.

I should note that there are several ‘stops’ along the way, such as the Sacred Tree Station (神木站), which some may consider to be a Japanese-era station when in fact it is really only just a platform, which is why I haven’t included it in the list.

-

Beimen Station (北門車站 / Hokumon / ほくもんえき) - Still in operation

Lumachan Station (鹿麻產車站 / Rokuma-san / ろくまさんえき) - Still in operation

Zhuqi station (竹崎車站 / Takezaki / ちくきえき) - Still in operation.

Mululiao Station (木履寮車站 / Mokuriryo / もくりりょうえき) - Still in operation

Jhangnaoliao Station (樟腦寮車站 / Shounoryo / しょうのうりょうえき) - Still in operation

Dulishan Station (獨立山車站 / Dokuritsu-san / どくりつさんえき) - Still in operation

Jiaoliping Station (交力坪車站 / Koriyokuhei / こうりょくへいえき) - Still in operation

Shueisheliao Station (水社寮車站 / Suisharyo / すいしゃりょうえき) - Still in operation

Fenchihu Station (奮起湖車站 / Funkiko / ふんきこ-えき) - Still in operation

Duolin Station (多林車站 / Tarin / たりんえき) - Still in operation

Shitzulu Station (十字路車站 / Jiyuujiro / じゅうじろえき) - Still in operation

Chaoping Station (沼平車站 / Shohei / しょうへいえき) - Reconstructed

Japanese-era railway-related places of interest

In addition to the Japanese-era railway stations that remain in Taiwan, there are also a large number of historically important buildings and places of interest with regard to the railway.

The most prominent of these being the three Railway Bureau Offices, which were the geographically strategic offices for the operation and maintenance of the railway.

There are also quite a few other places of interest, and this is where my list will ultimately continue to grow over time as there are a number of railway-related buildings currently in the process of being restored as well as a number of branch line-related sugar factories, which have been converted into culture parks.

-

Taipei Railway Bureau (台北鐵道部)

Hualien Railway Bureau (花蓮鐵道部)

Kaohsiung Railway Bureau (高雄鐵道部)

Taipei Railway Workshop (台北機廠)

Changhua Roundhouse (彰化扇形車庫)

Changhua Railway Hospital (彰化鐵路醫院)

Luodong Forestry Culture Park (羅東林業文化園區)

Taiping Mountain Forestry Railway (太平山森林鐵路)

Map of Japanese-era Railway Stations

Combining the three lists above, the map I’ve created below features all of the stations and Japanese-era railway-related places of interest in one convenient location. This should help you easily identify where you’ll be able to find these historic locations.

Each of spots on the map features basic information about the stations as well as links to articles about them, if available.

As you can see from the modest number of links I’ve provided, I still have quite a bit of work to do with regard to documenting the history of these stations - So, as I mentioned earlier, this article is very much a work in progress, and as I continue to work on a number of other ongoing projects, I’ll try to visit as many of these these historic stations as I can while traveling around the country.

That being said, I hope that this list and the map I’ve created for you are both interesting and helpful.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to get in touch!