Having visited Rome a few years back, and consequently writing a bunch of blog articles about the city and its history, I quickly learned about the importance of aqueducts, and how access to fresh and clean running water were essential in creating an empire.

A thousand years later, another empire-in-the-making on the other side of the world had just taken control of its first overseas colony, and found itself faced with the same problems as the Romans.

When the Japanese took control of Taiwan, they were confronted with a savage environment that had yet to be tamed or developed. It was obvious that the island was a treasure trove of natural resources that would contribute immensely to an empire bent on further expansion, but first the land had to be tamed and infrastructure had to be put in place to ensure that in the long-term, they would be able to reap the benefits of the islands full potential.

Despite many attempts, no foreign power had been able to occupy Taiwan before the arrival of the Japanese in 1895. Shortly after their arrival they quickly got to work on an ambitious military plan to ensure that they were able to completely control the island. This meant that not only the land would have to be tamed for development, but the people living in the country would have to accept colonial rule.

When it came to the latter, there was massive resistance, and the Japanese did what every other colonial regime has done throughout history - violently silenced any resistance.

That being said when it came to taming the land, it was one of the areas where the Japanese suffered the most, as the vast majority of military deaths in the early years of the occupation were due to unfavorable living conditions, and most notably, constant outbreaks of malaria.

For centuries, malaria had ranked as the most lethal disease in Taiwan, causing the deaths of people as famous as Koxinga (鄭成功), and (possibly) even Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa (北白川宮能久親王), a member of the Japanese royal family and one of the generals who led the Imperial Army’s expedition into Taiwan.

Note: There is considerable debate on the actual cause of his death.

When the Japanese started taking official records, both malaria and cholera were reported as the deadliest diseases in the country. So, to combat these problems, the colonial government invested heavily in developing an effective sanitation system, which included offering running water, sewage, storm drains, and improving the public health situation by ensuring that every community had access to a medical clinic.

They likewise included local citizens in their effort to eradicate the cholera problem by offering a bounty on dead rats, resulting in a somewhat comical situation where people would offer up a collection of rats bodies for a cash reward.

There are many things that can be said about governance during the Japanese-era, but the pace at which the Japanese developed Taiwan put the word ‘efficiency’ to an entirely new level, and as modern development took place around the island, these often fatal diseases gradually started disappearing, greatly benefitting the people of Taiwan and improving quality of life.

Part of the effort mentioned above was to start construction on water distribution facilities across the island. Starting in 1899 (明治32年), water services were supplied to Tamsui and within a few years, networks in Keelung, Taipei, Beitou, Changhua, Kaohsiung, Chiayi, Taichung, and Tainan were all gradually added to the list. Amazingly, by 1937 (昭和12年), there were almost ninety cities, towns and villages around Taiwan that were supplied with water service.

Link: Yuanshan Shinto Shrine (圓山水神社)

And yes, if you haven’t already guessed, one of the factors that contributed to this sudden improvement in quality of life, and the eradication of deadly diseases in Taiwan was thanks to the construction of aqueducts, which made fresh and clean water available to pretty much everyone in Taiwan.

Today I’ll be introducing the Japanese-era aqueduct in Hsinchu, which has recently been restored and reopened to the public as a culture museum and tourist destination on the growing list of Japanese-era buildings in the city that have been restored.

Hsinchu Aqueduct (新竹水道取水口)

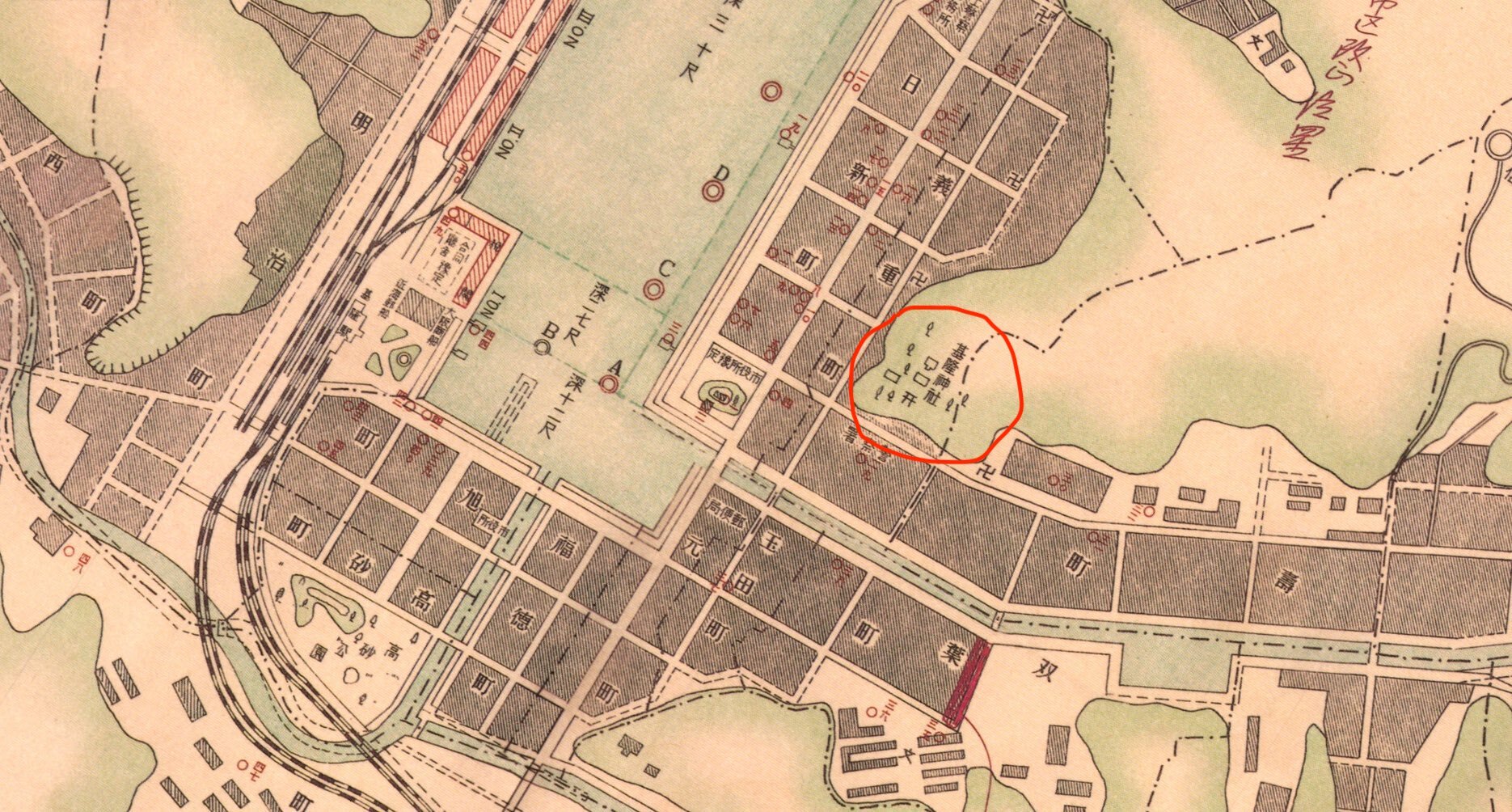

To better understand the history of the Hsinchu aqueduct, it’s probably a good idea to start by explaining a bit of history about Hsinchu during the colonial era. During that half century period, Taiwan’s administrative divisions were altered quite a few times before everything eventually settled down and became permanent. The reason for this is due to the fact that the boundaries of many of Taiwan’s major cities and towns started taking shape during this time thanks to the the construction of the railway, and the Japanese government’s various urban planning and development projects.

Prior to the 1920s, Hsinchu was just a small portion of the much larger Taihoku, which spanned from what we know as modern day Taipei to Yilan and as far south as Hsinchu. That all changed between 1920 and 1926 when the colonial government instituted a re-districting scheme, referred to as the Dōka policy (同化), which essentially split Taiwan up into eight prefectures (5州3廳) and aligned Taiwan’s administrative divisions with the rest of Japan.

As of 1920, Taiwan’s administrative divisions were as follows:

Taihoku Prefecture (臺北州 / たいほくしゅう) / Modern day: Taipei

Shinchiku Prefecture (新竹州 / しんちくしゅう) Modern day: Hsinchu

Taichu Prefecture (臺中州 / たいちゅうしゅう) Modern day: Taichung

Tainan Prefecture (臺南州 / たいなんしゅう) Modern day: Tainan

Takao Prefecture (高雄州 / たかおしゅう) Modern day: Kaohsiung

Karenko Prefecture (花蓮港廳 / かれんこうちょう) Modern day: Hualien

Taito Prefecture (臺東廳 / たいとうちょう) Modern day: Taitung

Hoko Prefecture (澎湖廳 / ほうこちょう) Modern day: Penghu

If you’re familiar with Taiwan’s geography today, you’ll notice that many of the Japanese-era prefectures remain mostly the same, but some have also been split up. Taihoku Prefecture for example once administered the areas we know today as Taipei, New Taipei City, Keelung and Yilan, all of which are administered on their own these days.

The Hsinchu of the Japanese era was similar in that Shinchiku Prefecture included Hsinchu City (新竹市), Hsinchu County (新竹縣), Taoyuan City (桃園市) and Miaoli County (苗栗縣). By the 1920s, Shinchiku Prefecture was home to one city (市/街) and eight districts (郡), following the standard structural hierarchy system set up by the re-districting scheme.

Within that scheme there were three major levels:

Level 1: Prefecture (州廳)

Level 2: City (市) / District (郡) / Sub-prefecture (支廳)

Level 3: Town (街) / Village (莊) / Aboriginal Area (番地)

Under this districting scheme, Shinchiku’s eight districts were divided up into at least forty five different towns and villages, with a population nearing one million people.

Why am I mentioning all of this? Well, its quite simple - As Shinchiku grew into one of Taiwan’s more prosperous prefectures, its population rose in kind and the necessity for continued development, and more importantly public sanitation became necessary for the growth of the city.

Fortunately, in 1914 (大正3年) , years before the urban reform policy took effect, the Governor General’s office had already started drawing up plans to construct a network of waterways to supply the area with running water. Those plans however ran into financial difficulties as the construction of water facilities would cost at least 400% of the annual tax revenue collected in Hsinchu, and required various subsidies and long-term low-interest loans from the governor-generals office in order to get the project started.

Construction on water facilities in the area however didn’t consist solely of the aqueduct that I’m introducing today, but also a nearby mountainside water treatment facility (水源地). Essentially the aqueduct was charged with collecting water from underground wells on the base of Shibajianshan (十八尖山), then sending it for processing to the water treatment facility putting it through the various purification facilities on-site before releasing it for distribution.

Note: The water-pump facility (a short distance away) has likewise been slated for restoration, so it is likely to also open to the public sometime in the near future.

Once the (extended) planning process was complete and funding was secured, construction on the water system started in 1925 (大正14年), and was amazingly completed five years later in 1930 (昭和5年), providing water service to the growing city for the first time, and likewise assisting in the effort to curb the further spread of malaria. As the city grew however, that single high-powered motor became insufficient, so a second pump room had to be added in 1940 (昭和15年), with the addition to the existing building taking two years to construct.

With so many pieces involved in the water distribution network, construction on the system was a little more complicated than just the completion of the aqueduct building. Unfortunately it is rather difficult to find much in-depth information about the historic Hsinchu Water Distribution system, so after quite a bit of research I’ve gone ahead and translated a bit of a timeline for you including the dates when the projects were started and completed:

Water Collection Well (集水井) - 1925/9 - 1926/11

Aqueduct well (唧筒井) - 1926/2 - 1926/11

Aqueduct pump-room (唧筒室) - 1926/7 - 1927/3

Diversion Well (分水井) - 1926/7 - 1927/3

Sedimentation Tank (沉澱池) - 1926/7 - 1927/5

Sedimentation Well (沉澱井) - 1926/7 - 1927/5

Filtration Pond (濾過池) - 1926/7 - 1927/5

Filtration Well (濾過井) - 1927/7 - 1927/12

Purification Pool (淨水池) - 1928/4 - 1928/10

Water Machine Room (量水機室) - 1928/7 - 1928/11

Pipe-making shop (鐵管敷設) - 1926/3 - 1929/2

Looking back, taking only five years to construct such a complex water distribution network is actually quite amazing, but from the old news articles I’ve read from the archives of the Taiwan Daily (台灣日日新報), the project was ‘delayed’ considerably and the period of construction on every piece of the network had to be extended, which would have been considered a pretty terrible thing for the Japanese authorities, who pride themselves on efficiency.

Construction was completed on February 20th, 1930 (昭和5年), but before turning on the taps, the network went through a period of inspection to ensure its safety before finally turning on water service for the people of Hsinchu City (新竹街) on April 24th of that same year.

If you’ve arrived here thinking the Hsinchu Aqueduct might appear similar to what you’ve read about in History books with regard to its Roman counterparts, you might be a bit disappointed. This aqueduct doesn’t make use of large bridge-like structures, allowing water to be transported from one place to another; This is because the Japanese had access to something the Romans didn’t - high powered motors.

Essentially, the “aqueduct” was a pumping station (唧筒室) that, as mentioned above collected water from groundwater and underground fresh water sources, as well as the Long-en Water Conservatory (隆恩圳), located directly behind the station. From there the water was transported up-hill to the nearby processing facility and put into one of the six various artificial wells where it would eventually be sent down-hill again to the city. (As depicted in the diagram below)

Given the period when the aqueduct was constructed, it shouldn’t really surprise anyone that its architectural design follows the ‘Art-Deco' style that was popular with the Japanese architects of the era. That being said, as I mentioned earlier, a second pump-room extension was added thirteen years after the construction of the original building, so you’ll notice that there is a slight difference in the architectural styles between the front and rear section of the building.

The reason for the difference is quite simple, the first pump-room was constructed during the heyday of the Japanese Colonial Era, while the second part was added during the Second World War, when the government’s coffers were pretty tight. So when you look at the front section of the building, you’ll notice the beautiful fusion of Western-Japanese design (和洋混合建築風), making use of the flowing Art Deco style, while the section that was added later was just a simple reinforced concrete designed building without much fuss.

The exterior of the aqueduct features beautifully stone-washed beams and a portico entrance that extends from the front of the main building. The mixture of timber and concrete in the design really adds to the building, especially when you’re inside as you’ll notice that the wooden window panes on all four sides of the building allow for a considerable amount of natural light to come into the building, making electric lights pretty much unnecessary during the daylight hours.

Likewise, one of the things that makes this aqueduct stand out from other Japanese-era structures is that even though it appears to be at least two-stories high from the outside, if you enter from the main entrance, you walk into a completely open space that was constructed below ground level. So when you’re inside, the ground-level windows are actually a level above you. Very few buildings from that era were constructed underground, but considering where the pump was located, it was necessary.

Interestingly, when the second pump-room was constructed, it was constructed on ground level only, and although it directly connected to the first pump room, it only featured a partial underground section where piping was located. This was likely part of an effort to save costs in construction, but could have also been thanks to an improvement in water-pump technology.

Another area where the addition stands out is in the design of its roof, which could be considered a typical Japanese roof. The original pump room had an almost flat roof that made use of gutters to ensure that rain water wouldn’t accumulate on top. The second pump-room on the other hand featured a curved roof constructed primarily of timber and was covered in black roof tiles. When you’re inside the building, you’re able to look up and view the network of trusses and beams that hold the roof in place and help to distribute its weight to ensure stability.

The original pump-station is a 99㎡ (30坪) building while the second pump room added another 79㎡ (24坪) and featured equipment imported directly from Germany and Japan. In the first pump-room, a 90-horsepower fuel-injected motor acted as the main pump with the help of a 75-horsepower back up. Later, the second pump-room added a newer 120-horsepower motor with the ability to pump around 6600 cubic meters of water per hour.

When the colonial era ended, the aqueduct and the water distribution system was used for another couple of decades, but eventually the population of Hsinchu grew to a point where the water supply became insufficient, requiring the construction of reservoirs in the nearby mountains. This problem was confounded by the founding of the Hsinchu Science Park (新竹科學工業園區), which likewise required a considerable amount of water resources.

The aqueduct ceased operation in 1981 and shortly thereafter was abandoned. As the years went by, nature took over and the building almost disappeared as it was overtaken by a jungle-like environment.

The Hsinchu City Government recognized the aqueduct as a protected historic property (市定古蹟) in 2011 and allocated funds for its restoration and conversion into a public museum.

If you click the link below, you can check out some of the photos of the building as the restoration project was first starting. One of the things that you’ll notice is that it was in pretty bad shape after being abandoned, and looks as if it was left open to the elements for quite a while. What confused me however was that someone added statues of standing Buddhas on the roof, with one of them ultimately losing its head for some reason.

I’m not particularly sure what the story was regarding them being placed on the roof, but sometimes these things are really random.

Link: 新竹水道 取水口 (Blair and Kate's 旅遊與美食)

Restoration on the aqueduct building was completed in 2017, and was reopened to the public as the “Hsinchu Aqueduct Museum” (新竹取水口展示館), allowing visitors to tour the building and learn about the historic of water service in the area.

However, due to recent periods of drought, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the building has gone through frequent periods of closure.

Ironically there is often a lack of water available at the former water-pumping station!

The Hsinchu Aqueduct Museum (新竹取水口展示館)

With the restoration of the aqueduct building completed in 2017, the Hsinchu City Government opened up the building to the public as a cultural museum. The restoration process most notably not only included fixing up the old building, but restoring all of the old machinery housed within as well. Today when you visit the museum, you’ll find a number of informative exhibits about the history of water network in Hsinchu, and you’ll be able to check out the old water-pumps as well.

A visit to the museum admittedly doesn’t take all that long as there are basically only two rooms to check out, but the local government has also provided spaces outside for people of all ages to enjoy, with a water-themed playground on the exterior of the building.

Unfortunately, the museum is in a bit of an awkward location, and is an area that doesn’t really attract that many tourists as most people who visit Hsinchu tend to stick to areas on the other side of the railway.

It seems like they originally figured that people would be interested in visiting the museum in tandem with a visit to the giant “Taiwan” lantern that was presented at an overseas expo a year back, but declining interest in the expo lantern forced the government to close it up, and they’re currently in the process of demolishing the site.

Nevertheless, if you’re in Hsinchu and you’re looking for something to do, I highly recommend stopping by to check out the beautiful building and the informative displays they have made available.

Visiting is free of charge, and I’m sure that when you visit you’ll be able to enjoy a guided tour (if you’d like one) as the staff there are always happy to receive guests!

Hours: Open Tuesday - Sunday from 9:00-12:00 and 1:00-5:00

In the future, the aqueduct museum will work hand-in-hand with the nearby Japanese-era water purification facilities that are currently under restoration. When they’ve got the rest of the network opened up for tourism, I’m sure there will be a bit more to see, and for me to introduce here.

Getting There

Address: No. 4, Dongshi Street, East District, Hsinchu City (新竹市東勢街4號)

GPS: 24.805520, 120.994270

Car / Scooter

If you have access to a car or scooter, getting to the Aqueduct Museum should be quite straight-forward if you input the address or coordinates provided above into your GPS or Google Maps. Once you arrive, you’ll find that there an ample amount of parking spaces available for visitors, so you won’t have to worry about looking for a space.

Public Transportation

If you’re relying on public transportation to get to the museum, you have a few options, but each of them is going to require a bit of a walk as the closest buses stops / trains are a short distance away from the museum.

If you’re taking a train into Hsinchu, you can either get off at North Hsinchu Station (北新竹站) on a normal train, or Quanjia Station (千甲車站), if for some reason you find yourself on the Neiwan Rail line (內灣線).

From each station you can walk to the museum in less than fifteen minutes. However both stations have access to YouBikes, so you can easily grab a bicycle and ride over, making things easier.

Link: Neiwan Old Street (內灣老街)

If you prefer to take a bus, you’re a bit more limited in your options, but you have the option of taking Hsinchu Bus #53, Shibo 3 (世博3號) or Shibo 5 (世博5號) to the ‘A-Mart Bus Stop’ (愛買二站) and then walking from there.

My only caution about that is that the ‘Shibo’ buses are limited in their service, and since you still need to walk for about five minutes, I’d recommend just walking from the train station or grabbing a YouBike.

Even though visiting the Hsinchu Aqueduct Museum won’t take much of your time, it is a pretty cool place to visit as there are very few of these Japanese-era buildings left in Taiwan. There are of course other areas around Taiwan where you can find historic water-related buildings, but this building is able to stand out thanks to its beautiful architecture and for the location where it was constructed.

If you’re in the area, I recommend stopping by to check it out.

References

新竹水道取水口 (Wiki)

臺灣日治時期行政區劃 (Wiki)

新竹州 (Wiki)

新竹水道取水口展示館 (新竹市觀光旅遊網)

新竹水道「取水口」、「水源地」指定為市定古蹟 (桃園新聞網)

新竹-新竹 新竹水道 水源地 (Just a Balcony)

新竹-新竹 新竹水道 取水口 (Just a Balcony)

新竹取水口 - 歷史沿革 (新竹文化局)

新竹水道發展簡史 - 張崑振 (Hsinchu Archives) | (LINK 2)